The fourth of Apple’s top 10 major areas of innovation in the last 25 years is 2003’s iTunes Music Store. Here’s how Apple transformed the music industry and created an entirely new digital media marketplace.

The first segment discussed Apple’s 2000 release of Mac OS X Public Beta, its first important area of innovation in the last 25 years. The second segment focused on Apple’s reinvented retail operations. The third segment introduced iPod. The fourth details how Apple brought retail to digital media within iTunes.

“Innovation” brings to mind the explosive new creations of the iMac, iPod and iPhone. But the greatest potential opportunity for change can also come from a devastating destruction of the status quo, paving the way for something really new.

By the year 2000, the foundations of the enormous 20th Century recording industry had been fatally struck by file sharing. Over the next 25 years of the new millennium, Apple tasked itself with a global rebuilding of the music industry. The alternatives could have been terrible.

The commercial lifeblood of all cultural expression from studios and theater, animated by decades of work devoted to licensing and performing rights and infused with everything that perpetuated the existence of Old Media, had been blind-sighted in the late 90s by the sudden impact of the digital Internet.

The vast global business of CD sales was effectively left for dead as an enormous roadkill on the information super highway. Rapid advances in bandwidth and processing speeds in the late 90s suddenly turned the CD from a physical media into a stream of bits that could be duplicated and rebroadcast anywhere, effortlessly.

The collapse of the initial internet bubble “dot com” economy, starting in 2000, helped to deflect some panic away from the music industry, but the reality was clear: the CD sales that had been inflating the music industry were now leaking air with the violence of the Hindenburg.

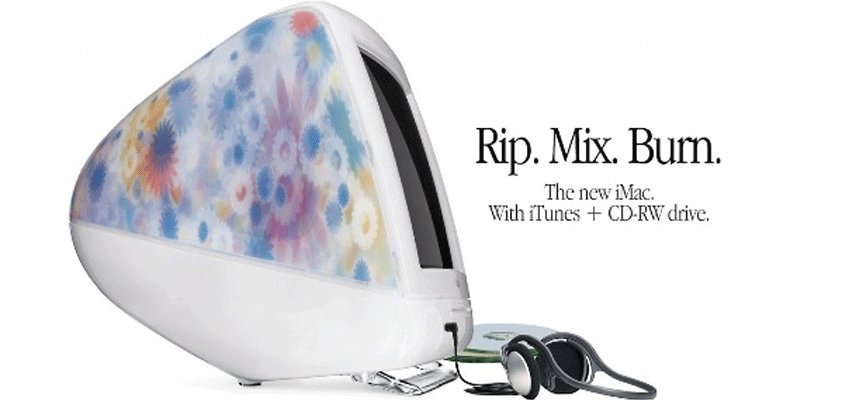

CDs sales hit a $22 billion peak in 1999 just as Napster file sharing, burnable CD-Rs and new trend towards mobility opened up alongside iPod.

Suddenly the global music industry was facing a crisis similar to the one Apple itself had experienced in the 90s. If anyone can copy all of your work, without paying you anything, you’ve got nothing.

When Microsoft stole the core foundations of the Macintosh, Apple had to scramble together a new newer, better Mac experience to fight for a right to exist. Now that everyone had free rein to copy and paste digital music, the industry had to figure out how to create and sell a new digital experience.

They were unable to figure this out on their own. Sony, which had helped build recording hardware with its iconic Walkman, had also delved into the software business. It was making the memory and processors and recordable optical technologies that were imperiling the same recording business it now owned.

Sony attempted to create a new MiniDisc format that would use its ATRAC DRM security to prevent buyers from ripping and mixing their own music. It hoped to use its ATRAC music format to enable a digitized version of CD sales that could work across PCs and music devices, but couldn’t quite pull things together.

In fact, much of the music industry was seeking to find a simple replacement for CDs that could hold back the tide of permissive file sharing with some sort of encryption. They hoped to get right back to selling increasingly expensive albums with just one or two hit songs, as they had been for years.

Microsoft similarly pursued its own Windows Media DRM, seeking to tie digital rights management to Windows. The music labels desperately needed some solution, but didn’t want to hand over control to an existing monopolist either.

That made Apple an attractive alternative. The fledgling return of Apple, its new Mac OS X alternative platform and its experience in digital media with QuickTime all helped create a viable third option that promised a better experience for users, contained within the sandbox of Apple’s higher end customers.

Steve Jobs negotiated deals with the existing five major recording labels, Universal, Sony, Warner, EMI and BMG, which allowed Mac users access to buy 99 cent songs and $9.99 albums using Apple’s simple FairPlay DRM in the new iTunes Music Store in the spring of 2003.

Apple’s new iPod and iTunes-equipped Macs had been enabling users to listen to music from their own CDs as well as songs distributed as MP3 files. The new iTunes Music Store created a legal marketplace to allow buyers to browse and download new music, and pay for each track individually.

While iTunes couldn’t change the fact that Napster, Kazaa and other “free” sharing platforms existed, it did create a functional, easy to use retail experience as welcoming as Apple’s own retail stores created to sell Macs and iPods.

Cut from the same cloth

Apple had just raced to assemble its own direct retail Mac efforts online in 1997— using the WebObjects technology it had acquired from NeXT— giving itself the ability to reach hardware buyers and customize an online buying experience right in their web browser.

Apple now wanted to expand the concept of a digital storefront from selling hardware to selling software. And it wanted to integrate the store right into iTunes.

Part of the work to deliver the iTunes Music Store came from Apple’s parallel efforts to adapt an open source web browser: the KHTML-based Safari, first released in 2003.

Microsoft’s Internet Explorer and Mozilla’s Gecko were both bloated and slow, so Apple began working with KDE’s rendering engine to create a modern, streamlined new web rendering system that could be deployed as both the Safari web browser, an embedded into iTunes as WebKit.

Within iTunes, WebKit could be used to create a secure, dynamic store for new digital content, starting with recorded music.

By focusing on what users wanted and delivering an easy to use catalog of downloadable music, Apple not only secured itself a supply of commercial music for its Mac and iPod users, but also created the foundations for selling and renting films, music videos, iTunes Extras and eventually iPod games.

Microsoft and Sony had been trying to build castles that could control the distribution of digital goods, but their efforts failed because they didn’t focus on the experience of users.

Microsoft promoted Windows Media DRM as “PlaysForSure” across the industry as a broadly licensed initiative in the same manner as Windows. Sony tried to sell a tightly integrated experience that required its own formats.

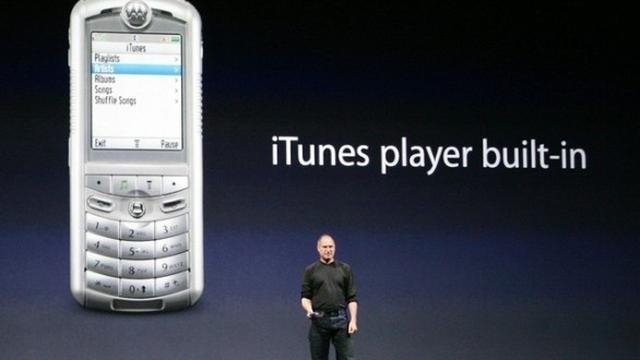

Apple responded to what its audience wanted, and delivered innovations to delight them. In 2005, Apple appeared onstage with Motorola’s ROKR E1 iTunes phone, which brought iTunes integration to other devices. But then Apple focused on its own new iPod nano at the same event, occupying space in the mobile world while expanding its music presence.

Apple was also promoting digital connectivity with mobile phones with contacts and calendar synching, just as it had been with iPods. It was again laying the foundations of the mobile future while remaining focused on what it was presently selling. Until 2007, that was iPods. But the groundwork for a full mobile desktop device running apps like the Mac was coming together.

Other companies were already pursuing the concept of selling mobile software online. Palm opened its Pilot PDA software store in 1997, and tried to build an ecosystem of digital app sales. Piracy and security issues resulted in an uncertain market for developers, who had to charge significant fees for their apps to recoup their investment. Most of their apps would end up being copied around like Napster’s music file sharing.

Windows Mobile also tried to operate a software marketplace selling smartphone titles, along with Nokia’s Symbian platform and Sun’s Java ME, but developing and distributing apps proved to be as difficult for mobile players as music was for the labels. Nothing was catching on anywhere, and it looked like software markets were in as bad of shape as the prospects for legal music and movie downloads.

Apple’s open invitation within iTunes to access your own music and also purchase tracks via its Music Store resulted in rapidly growing economy of scale that expanded into TV and movie downloads in 2005.

Firing on all cylinders

Apple introduced iPod Video in 2005, along with a new Video Store in iTunes offering a limited selection of TV shows priced at $1.99. Building upon iTunes success in music sales, the slow introduction of paid video downloads began with “standard definition” videos that could play within iTunes, on a video iPod, or later on Apple TV.

Apple embraced the concept of subscribed content feeds for mobile users, adopting the name Podcasts after its music player. It added automatic downloads and distribution within iTunes.

The following year Apple released a selection of $4.99 iPod Games, ranging from its own Texas Holdem to titles like Bejeweled, PacMan, Tetris and Mahjong from partners. Apple was making rapid progress in not only building the tools to develop mobile games, but also in building the infrastructure to distribute and market them.

Apple’s work with iTunes was also supporting its development of its Safari web browser and embedded online stores, building the foundations for its subsequent launch of the iPhone and its App Store. iTunes and the iPod would ultimately become components of the iPhone itself, serving as the “wide screen iPod” feature tied to its phone and internet communicator trio of defining elements.

An evolving digital content platform

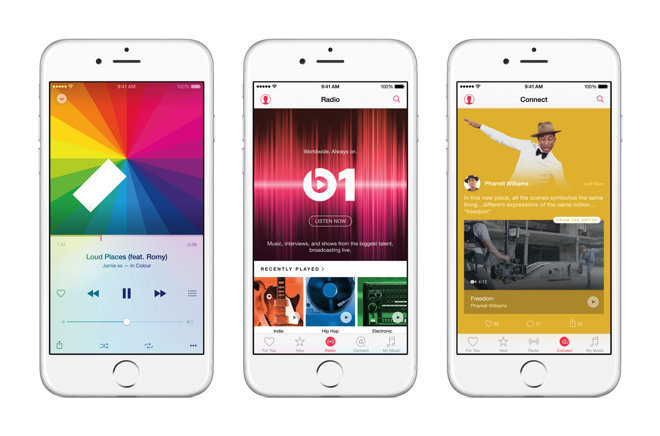

Apple’s efforts to develop a retail marketplace for digital content created the model for not just the App Store, but also the company’s further expansions into media with Apple Music in 2015 and Apple TV+ in 2019.

Along the way, Apple increasingly worked to make iTunes Music higher quality and more flexible for users. In 2004 it introduced ALAC (Apple Lossless Audio Codec) for high-quality audio without compression. It introduced iTunes Plus In 2007, which offered higher-quality, DRM-free music at a premium price, doubling the bitrate to 256 kbps AAC.

In 2008 Apple released Safari 3.1 with support for HTML5, enabling native media playback on the web without plugins. It focused on the future of digital media with H.264 and H.265 video, moving beyond the world formally tied to Flash. Other media codecs were replaced with web standards as QuickTime Player 10 was introduced the following year. In 2011 Apple introduced AV Foundation in macOS (10.7) Lion and iOS 4 as a modern framework for handling audio and video.

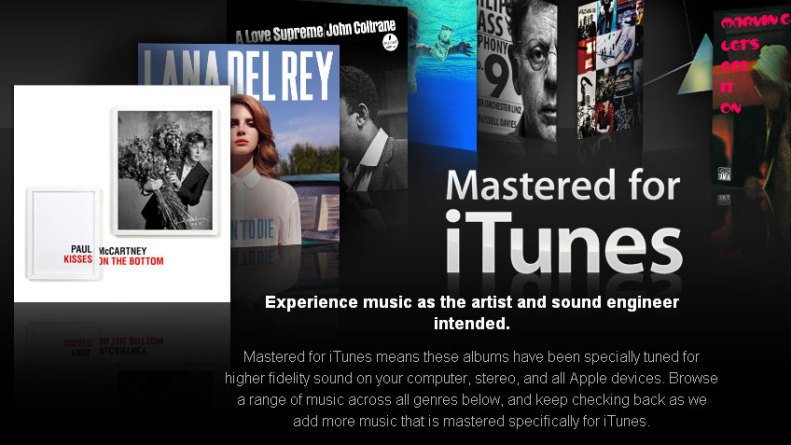

In 2012 Apple introduced Mastered for iTunes, a higher quality format that starts with 24-bit, 96 kHz masters instead of standard “CD-quality” 16-bit, 44.1 kHz audio. Using Apple’s own AAC encoder, it produces 256 kbps AAC audio that sounds virtually lossless, preserving more detail and dynamic range from the original studio recordings.

In 2019 Apple’s bespoke mastering was rebranded as Apple Digital Masters. Having such tight integration with recording studios already, Apple was in a unique position to introduce a new level of sound quality in 2021: Spatial Audio. This similarly required specialized track mixing by the studios. It effectively created a 3D soundscape that could be reproduced by speakers or headphones.

Support for Apple Digital Masters, Lossless Audio, and Spatial Audio were included at no additional cost in Apple Music, setting the service apart as providing far higher quality than rival services like Spotify, while also providing a unique feature for Apple to include in its sound hardware.

Spatial Audio also paved the way for creating Immersive Video with Spatial Audio on the new Vision Pro, creating a fully surround-immersive experience using familiar tools.

Apple’s relentless efforts to innovate in music and in the sales of digital media have given the iTunes Music Store an incredible legacy of industry firsts that have changed the entire nature of the content business— one that Apple now directly participates in as a content producer for Apple TV+ and the Vision Pro App Store.

The original impact of the iTunes Music Store was closely tied to the explosive growth of iPods. It helped create fertile grounds for launching iPhone and its own App Store market for mobile apps. But it was also forced to adapt and change as new technologies and emerged outside the company.

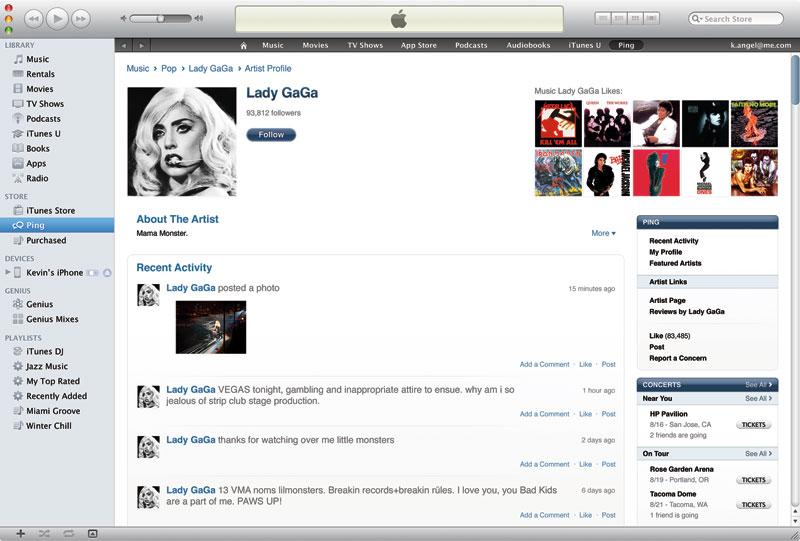

Apple initially worked with Facebook to build a social media component into iTunes. After a dispute over access to user data, Apple launched its own social features for iTunes 10 in 2010 as Ping.

Facebook not only backed out of partnering with Ping, but also withheld its Facebook app from the new iPad, hoping to throw its support behind tablet rivals. Apple’s solo efforts with Ping were troubled by spam and the problems of trying to moderate an online public space.

Apple abandoned Ping and instead explored efforts to integrate directly with Twitter and Facebook in iOS 5 and 6 in 2011-2012. At the same time, Apple began work on iCloud to deliver its own suite of online services without a social component.

Apple increasingly pursued a closer, direct relationship with its customers rather than trying to connect them together into a social grid. This direction led Apple into promoting security and privacy rather than wide, permissive sharing of data and acting as an intermediary that siphoned off collected data for marketing purposes.

Other big industry players took the opposite path. Facebook worked with Android licensees to deliver an experience centered around Facebook. The 2013 HTC First put Facebook photos on its cover screen and tried to keep users locked inside the world of Facebook and Messages.

Facebook’s phone failed, its tablet partnerships failed, and its repeated subsequent efforts to snub Apple and push Facebook as the home page of mobiles failed. Apple eventually pulled the plug on Facebook integration in iOS 11 in 2017, leaving Facebook and other social media networks as standalone apps on an otherwise privacy centric platform.

Google tried to buy its way into social media with Orkut, then integrated Buzz into Gmail in 2010 and launched the Facebook-like Google+ the next year. Google not only failed at launching its own social media efforts, but also failed to push its own devices as compelling mobile alternatives tied to advertising, at least outside of low end, high volume “carrier friendly, good enough” Android devices sold by licensees.

Apple ended up winning in social media by choosing not the play in the surveillance advertising market. Instead, it build a reputation as the choice for privacy and data security, which became increasingly more attractive as the public began to understand how social media networks and advertisers were using their data, making them the product to be sold to advertisers.

iTunes at Home

Across the 2010’s Apple also introduced deeper integrations between iTunes and the home. It relaunched its AirTunes wireless music streaming to speakers as AirPlay in 2010, adding new support for video and screen mirroring. The iTunes Music Store also expanded into TV and movie sales and brought content to Apple TV, which slowly grew as a media center for watching iTunes content on your TV.

Despite longstanding rumors that Apple might launch its own TV set, the company instead “pulled the string” to see where things were going with an incremental rollout of Apple TV devices that brought higher quality videos and rental options into the home.

Despite many cheaper, ad-centric offerings, Apple TV continued to gain in popularity as an iTunes Store for your TV through the 2018 introduction of AirPlay 2, which brought multi room streaming to Apple’s products, and licensed the protocol to other TV and speaker makers. AirPlay 2 was broadly adopted by TV makers as a high quality, flexible streaming option catering to iPhone users.

The next year, Apple followed suit with licensing its Apple TV app to other TV makers. Since 2020, Apple has spread Apple TV as an app across platforms ranging from Roku, Amazon Fire TV, PlayStation, Xbox, Google TV and Android TV, acting as the modern equivalent to the iTunes Music Store of the last decade.

In this market, rather than building all the TV hardware, Apple has pursued making the content to play on them with Apple TV+ and its various partnerships to deliver content through its store.

Apple has introduced its own speakers with HomePod and HomePod mini, and continues to develop Apple TV as a standalone product for high quality streaming to any TV. Both also integrate into its HomeKit licensing and AirPlay 2, making it easy to connect smart devices, home cameras and other sensors, and to operate these with Siri voice commands.

Rumors are now swelling that Apple sees potential opportunity in bringing new connected devices for managing the home. And of course, Apple’s release last year of Vision Pro is the latest expression of the concept of a productive, creative experience integrated with a digital storefront offering their party apps and access to existing media and new content in new formats, including the emerging space of Immersive Video and interactive AR experiences.

The shift to streaming

From its beginnings as an integrated WebObjects store inside iTunes, Apple’s Music Store increasingly shifted to new technologies as they became available. As Apple’s Mac platform matured and was joined by the mobile iOS as an apps platform, Apple’s work to modernize and improve its development tools resulted in regular updates to its iTunes app and the servers running the iTunes Music Store.

In 2011 Apple launched iTunes Match for storing music libraries in the cloud and streaming on demand. iCloud integration made all iTunes purchases available for streaming or download from anywhere. In 2012 Apple introduced iTunes Radio as a streaming option similar to Pandora.

Despite many failed efforts to launch “rental music,” notably including Microsoft’s failed Zune subscriptions, Spotify was finally catching on a viable streaming alternative to the iTunes world of downloads. Its success came largely from paying artists virtually nothing for streaming rights, eating up sales of iTunes downloads the way file sharing had devoured CD sales.

In 2014, Apple acquired Beats Music as its largest ever purchase at $3 billion. It initially incorporated Beats as a brand for speakers and headphones.

The next year, it launched Apple Music, using Beats music streaming product, to create a hybrid service of downloads and subscription streaming. It subsequently phased out music purchases and focused on streaming.

In 2017, iTunes ultimately disappeared from iOS and was replaced by standalone apps for Music, TV and Podcasts. In 2019 Apple followed suit on the Mac, replacing iTunes with the same new standalone apps for Music, TV and Podcasts in macOS Catalina. The new apps make use of Apple’s latest development tools and are optimized for modern hardware.

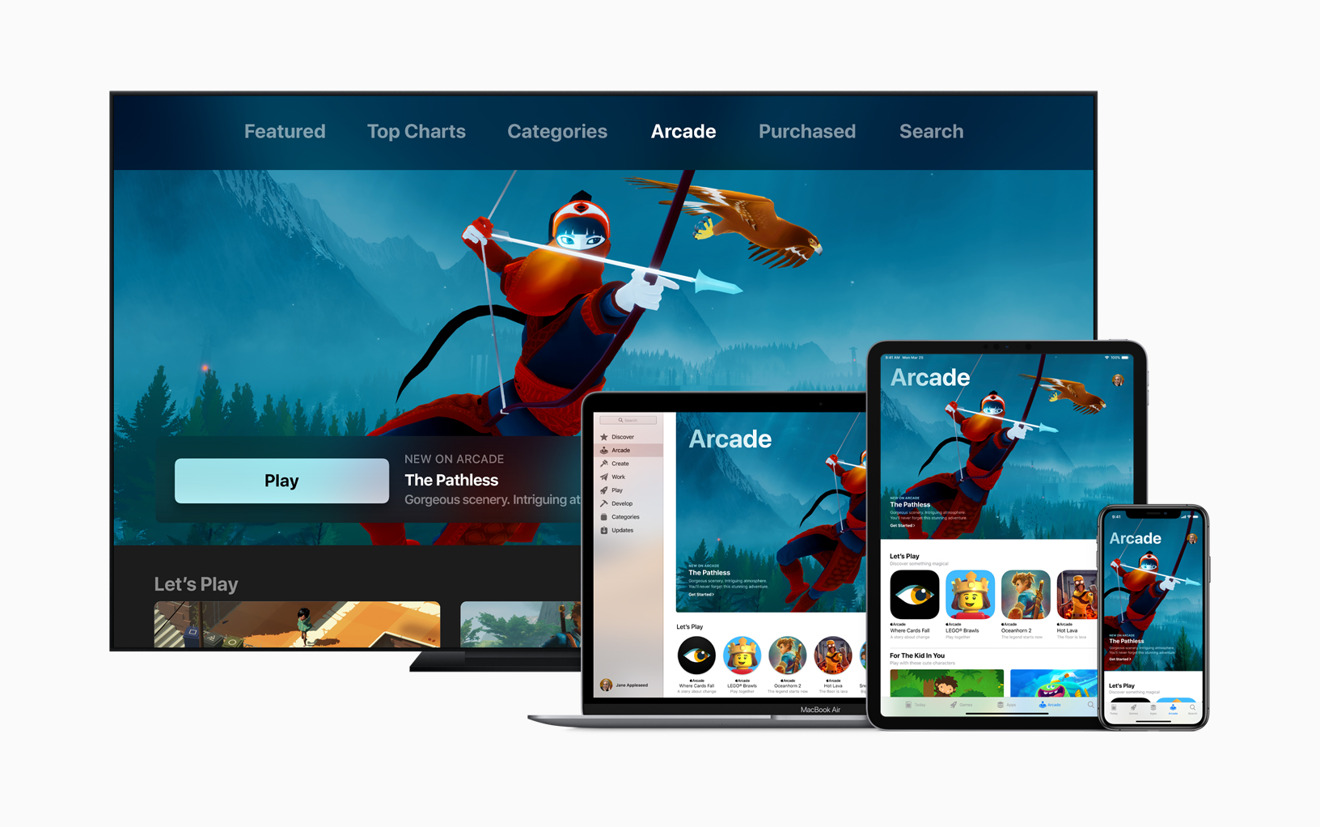

As iTunes disappeared to make way for new apps, the iTunes Music Store was replaced by Apple Music, the standalone App Store, and services including Apple TV+ and the new Apple Arcade service of games running across Macs, Apple TV and mobile devices.

Apple’s history of innovation with iTunes and its Music Store continues everywhere it sells and produces digital content. It’s extraordinary that Apple developed the most widely known brands in the music industry and then boldly moved away from them to keep pace with the future.

The amount of innovative work Apple put into developing and constantly retuning its efforts in music and media sales is a major reason why it was so successful— even as others struggled to copy it or best it with alternatives. And we’re still not even halfway through the top ten innovations of Apple over the past 25 years!