To print this article, all you need is to be registered or login on Mondaq.com.

Let’s talk tech and Chinese money.

Since antiquity, China had led the world with its

adoption of cutting-edge currency

Today, there is an immense amount of interest surrounding

China’s new digital yuan (“DCEP“

– Digital Currency Electronic Payment).

However, China’s history of currency innovation goes back to

ancient times. Unlike Roman coins, ancient Chinese coins are marked

by a square hole in the middle, allowing the bearer to efficiently

string large amounts together for ease of transport.

A “开元通宝”,

kāiyuán tōng bǎo; ‘Circulating

treasure from the inauguration of a new epoch’. Attribution:

Unknown.

Another innovation was the use of bolts of silk. In ancient

times, silk was issued to garrisoned troops along the silk road as

a form of payment, because it was lighter than coins and easier to

transport overland from the then-imperial capital of Chang’An

(present-day Xi’an).

A plain, basket-weave (one thread over, one thread under) bolt

of silk from the 3rd or 4th century CE and

currently housed at the British Museum. Before it snapped in half,

this bolt was sent as payment to garrisoned Chinese troops in the

silk road city of Krorän (also known as Loulan). Attribution:

Valerie Henson, The Silk Road, Colour Plate 5A.

Promissory bank notes appeared a few hundred years after silk

bolts were used, in Tang dynasty China. These promissory notes

allowed merchants to conclude large transactions without needing to

carry heavy loads of metal coins (Tiě qián,

贴钱) on their person. Another few hundred years later,

real paper currency (Jiāo zi, 交子) appeared in

Song dynasty China (although Chinese paper already existed when

silk was used as payment, it was mostly for wrapping and it took

some time for paper currency Jiāo zi to emerge).

China is starting a new chapter in its currency

innovations

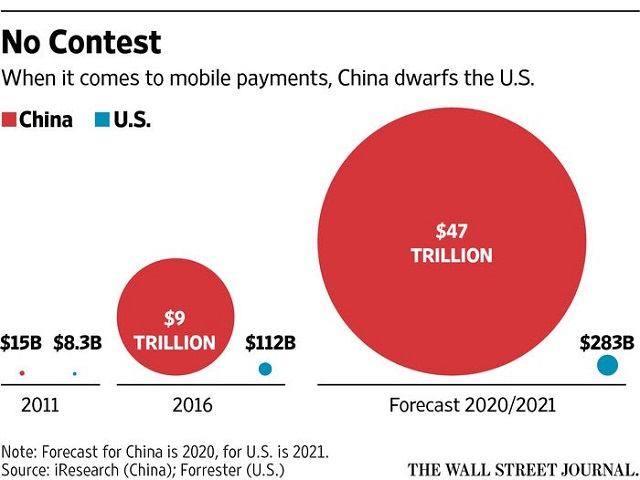

Fast forward to today: with the proliferation of Wechat Pay and

Alipay during the 2010s, China has, more than a millennium after

inventing paper bank notes, become the first major economy to

transform into a cashless society. In this regard, China is already

miles ahead of other developed markets.

In line with its history of currency innovation, China is again

writing a new chapter. However this time, there is one major

difference. Past Chinese improvements on money were usually

incremental. Paper and silk are lighter than copper, and digital

wallets weigh no more than the smartphone they’re carried. That

latter also bring some additional record-keeping features, like a

basic receipt for the parties’ reference.

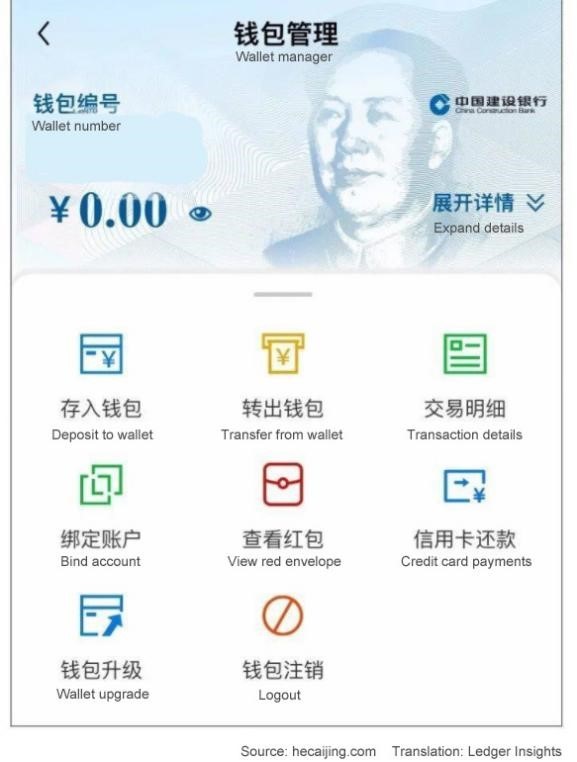

Unlike these incremental evolutions, the DCEP is a revolutionary

advance in currency. Allowing

near-instant foreign exchange settlement and built on

blockchain, the DCEP is perfectly traceable and allows the

People’s Bank of China (“PBOC“,

Chinese Central Bank) and state owned banks to collect data not

only on transactions between users (the parties, the date, and the

amount exchanged, among other details) but also on each subsequent

transaction using DCEP. There is immense potential for using this

ledger data to fuel the growth of fintech in China.

To better understand this, imagine for a moment if every

transaction for every US Dollar in circulation — for the

lifetime of each dollar — were recorded by the Federal

Reserve on a ledger. These dollars are stored and exchanged in

digital wallets, each of which has an “address” (like a

bank account number) tied to a person or company.

Whether in New York, Paris, or Shanghai, the Federal Reserve now

knows the name, timestamp, and amount exchanged for every

transaction completed in USD. Now imagine that the Federal Reserve

makes this data available to tech giants, either to help detect

crime, encourage innovation, or even to help the government raise

money. Imagine also that they share this information with law

enforcement to help them identify and catch criminals, and fight

money laundering and tax evasion.

Obviously, the Federal Reserve won’t be able to realize

these scenarios for legal and political reasons. It is very limited

in what it can do with a digital dollar. It would be illegal for it

to sell user data without user consent and privacy concerns in the

US would quickly lead to public backlash against sharing data with

law enforcement programs. It should be noted that the US Federal

Reserve is considering a Central

Bank Digital Currency (CBDC),1 though this has yet

to launch and its scope is set to be much narrower than in the

scenarios described above.

The PBOC, on the other hand, is more than ready to push a

digital currency to its fullest potential, from government

departments to beyond China’s borders. As of January 2, 2020,

the

PBOC had already filed 84 patent applications for the DCEP, and

the DCEP is

scheduled to be in use in time for the 2022 Winter Olympics in

Beijing. The plan is to first implement its use across

government institutions, then large Chinese companies, and then

finally to help forge a path along the new land, maritime, and

“digital” silk roads as a settlement layer in the Belt

and Road Initiative (“BRI“). Former PBOC

Governor Zhou Xiaochuan

recently spoke at length on the potential for the DCEP to

transform cross-border trade.

There are plans to share DCEP data to fight crime. According to

Yao Qian, founder of the PBOC’s Digital Currency Research Lab,

the

DCEP’s data will also be shared with law enforcement. Of

course, as suggested in

a report by the Bank of International Settlements, the benefits

to law enforcement could be minimal because ordinary criminals will

tend to avoid a fully traceable currency. That said, it could be

used to great effect to fight white-collar crime and corruption.

For example, after government treasuries convert all Yuan to the

DCEP, their spending (and the spending of government contractors)

could be tightly monitored. This may lead to much greater

transparency in areas like government product procurement,

construction, and other public tenders, which are particularly

vulnerable to bad actors. Similarly, once large companies convert

to DCEP, it follows that their staff payroll and a funds paid to

suppliers will also be traceable.

Moreover, there are already plans in place for the

mass-commoditization of data in China, which may enable marketing

DCEP data. This year, it was revealed that Shenzhen will establish

a “data trading market” and “take the lead” in

exploring new mechanisms for data property rights protection and

utilisation (see 2020 Implementation Plan for the Pilot

Comprehensive Reform of Building a Pilot Demonstration Zone of

Socialism with Chinese Characteristics in Shenzhen). To be

clear so far, there is no indication this this is intended to

market DCEP data, but it does open very interesting opportunities

should the government decide to do so.

Implications of China’s DCEP for Insurtech &

Insurers

In terms of creating Insurtech products for end-users, the

DCEP’s implications for Insurtech depend in part on whether and

to what extent the DCEP will enable or support smart contracts.

Smart contracts are already featured on other crypto tokens, most

notably the Ethereum Virtual Machine

(“ERC-20“) which supports developing

smart contracts by using the Solidity programming language, a

combination of Javascript and C++.

While initially a cause for alarm in some jurisdictions,

blockchain smart contracts hold great potential that is

increasingly well-understood by regulators. In addition to powering

the telematics behind Insurtech products (for more on the potential

for telematics in China see our past article,

“Can Foreign Investors Capitalize on Insurtech’s Growth in

China?”), smart contracts enable automating transfers of

rights in exchange for funds and lowering transaction costs

(especially for multi-party agreements).

This technology forms the basis of Initial Coin Offerings

(“ICO“). Through ICOs, smart contracts

allow a fundraising venture to execute only after sufficient

investors have agreed to the financing terms. In exchange for

funding the venture, the investors receive a token, a kind of

digital share certificate recorded on blockchain.

Although ICOs provide an innovative and potentially important

vehicle to support fundraising for new ventures and ideas, lack of

regulation and rampant fraud raised serious regulatory concerns

when they became popular a few years ago. For more on this, see

Zetzsche et al., “The ICO gold rush: It’s a scam, it’s

a bubble, it’s a super challenge for regulators”,

Harvard International Law Journal, vol. 60, no. 2, 2019.

ICOs have been banned in the PRC Mainland since September 2017 (PBOC, CAC,

MIIT, SAIC, CBRC, CSRC, and CIRC Announcement on Preventing

Financial Risks from Initial Coin Offerings).

While ICOs remain restricted in the PRC, they are now legally

regulated in

Hong Kong and

Taiwan as Security Token Offerings

(“STO“). STOs combine the power of an

ICO with the stringent regulations of the securities market.

Integrating the digital Yuan with an eventual STO regime would

be revolutionary in a couple of different ways. First, allowing

STOs — whether in Hong Kong or in the PRC assuming they are

legalized — to be denominated in DCEP would greatly benefit

fundraising for this innovative space. This would be a win for both

private investors and the government: investors gain access to a

powerful new fundraising tool, while the government can monitor and

regulate STOs under its financial exchanges by bringing them within

the fold of Chinese securities laws. This would allow regulators to

implement mandatory disclosure rules to protect investors from the

risks of fraud associated with ICOs, and further displace

unofficial cryptocurrencies by channeling existing ICO action into

the legitimate STO system. Together, these changes would make

institutional investors more likely to treat STOs as serious

investment opportunities. As a result, enabling the DCEP to support

STOs would cement the DCEP’s appeal for fundraisers and

institutional investors while helping the government keep tabs on

this new activity in public exchanges.

Legalizing STOs and allowing them to be denominated in DCEP also

opens up major new underwriting opportunities for property

insurers. Say, for example, that an opportunity presents itself for

a new insurance line of business — a new Chinese rocket

company wants to launch missions into space to replenish the

International Space Station, or launch a new satellite. Given the

risks, it cannot find an insurer willing to underwrite and sell

such an insurance policy.

With a DCEP-denominated STO, an insurer could decide to

underwrite such a policy on the condition that an STO

attracts an adequate number of co-insurers and reinsurers, and then

exchange the tokens as financial assets. If there’s adequate

market interest after the STO is listed, then the policy would

launch (as would the rocket ship!), be divided into token shares,

and then be distributed into each insurer and reinsurer’s book

of business in exchange for their DCEP payments. After the STO is

written, all of these subsequent steps would happen automatically

and significantly reduce transaction costs. Innovations like this

are already occurring, for example Nexus Mutual, a blockchain company

providing a decentralized financial alternative to insurance

cover. Depending on how innovative the regulators wish to be,

such “policy tokens” could then be resold as securities

to investors on the Shanghai, Shenzhen, or Hong Kong stock

exchange.

In an interview with Sergey Nazarov, co-founder of Chainlink (a

company developing “oracles” for smart contracts), one

possibility under discussion is for the revenue from such policies

to even become tokenized, and then bought and sold as a

fixed-income investment asset.

Due to its instant settlement capability, denominating these

investments in DCEP would also open the door for participation from

foreign insurers provided that they satisfy market access

requirements (for more on this, see our past articles,

WFOE Shopping — How Do Beijing, Shanghai, And Shenzhen

Compare For Establishing An Insurance WFOE In China?; and

China, GATS, Trump: Do Non-US Insurers Get A Piece Of The

China-US Trade Deal?).

Second, integrating the DCEP with an STO regime would be

particularly welcome for insurance investors, for whom restrictions

on equity investments were recently relaxed in November 2020.

Coming into effect on November 12, the Notice on Matters

Related to Insurance Fund Financial Equity Investment (the

“Notice“) lifts a significant number of

prohibitions on equity investments by insurers. In particular, it

divides permissible investments into a positive and a negative

list. Generally, as long as an equity investment prospect is safe,

liquid (stable cash flow and a track record of dividends),

profitable, legally registered and not engaged in serious legal

disputes, is led by an honest team, presents no risk of

related-party transactions, is not involved in real estate, is not

a serious environmental polluter, and is not on the NDRC’s

negative list,

then an insurer is free to invest in it. Although in practice a

significant number of ICOs were risky, failed, and would not meet

these criteria for investment, in theory this opens the door for

lucrative new investment opportunities if the government opens the

door to PRC STOs with sufficient securities regulations in

place.

While this DCEP/STO revolution is far from a reality, the

government is already moving towards an “internet of

blockchains” that would allow the DCEP to work far better with

existing smart contract ecosystems. One government initiative, the

Blockchain Services

Network (“BSN“,

区块链服务网络, qū

kuài liàn fúwù wǎngluò) is

designed to allow cross-platform compatibility and support popular

Western frameworks such as “Hyperledger Fabric (already

supported), Ethereum, EOS and Digital Asset’s DAML” (

Forbes). The BSN is aimed at “providing a robust,

low-cost, high-availability, multi-cloud, internet-of-blockchains

infrastructure”, and was launched in collaboration with large

Chinese enterprises including UnionPay, China Mobile Communications

Corporation, Design Institute, and China Mobile Communications

Corporation Government (ibid).

As for personal insurance, this would depend in large part

whether and to what extent DCEP data will be turned over to the

private sector. Realistically, most personal data would be

off-limits — absent user consent, we most likely will not

enter a dystopian future where central banks sell data on personal

lifestyle habits to insurers in order to adjust health policy

rates. However, as discussed above, it would be feasible

for the PBOC to make some personal data available to some financial

institutions in order to help fight financial crimes, and this may

including combating risks such as insurance fraud. It would also be

feasible for new insurance contracts to stipulate that some

benefits will only be paid out in DCEP. While insurers would not

collect DCEP data, they may thereafter be able to request

production of such data in the event of a lawsuit disputing the

claim, and detect suspicious activity after the benefits are paid

with the help of forensic experts.

Besides fraud prevention, one form of data that would be

particularly helpful is data on insurance disputes. Insurtech

smart-contracts could feasibly house not only insurance policies,

but also dispute resolution provisions which connect to mediation,

arbitration, or even Chinese internet courts. One example,

SageWise, already provides a dispute resolution clause to be

integrated within smart contracts. The data generated from

disputes, i.e. the nature of the disputed claim, the amount, and

the party which prevails, could help regulators identify and take

action against standard clauses showing a high-frequency of

disputes, while allowing insurance companies to better allocate

resources in drafting and communicating sensitive policies to their

clients. This would allow not only resolution of disputes, but also

prevention of future disputes.

If allowed to be used by the private sector, we can expect there

to be strict guardrails in place for how DCEP data is used, which

would make it especially difficult for foreign insurers seeking to

enter China’s Insurtech market to satisfy local requirements.

Under Article 37 of China’s Cybersecurity Law (2017)

(“CSL“), Chinese citizens’ personal

data, together with critical business data collected in China, must

be stored within mainland China, and companies must undergo a

security assessment before exporting such data across the border.

Thus although possible to make visible from an insurer’s

headquarters in London or New York, this would almost certainly

require a local Chinese partner or subsidiary that can pass the

CSL’s security assessment prior to sending such data to a

foreign server.

Conclusion

From bolts of silk to blockchain bits and bytes, China has a

rich history of currency innovation that continues to the present

day.

This time, China is implementing a currency innovation so

revolutionary that it will take years to fully grasp its potential.

The DCEP allows near-instant settlement and will play a significant

role in the land, maritime, and digital silk roads, with the

potential to transform cross-border trade.

Legalizing STOs and allowing them to be denominated in DCEP

would unleash a wide range of new investment and underwriting

opportunities for insurers. The DCEP would be especially powerful

if it can support smart contracts. As for data, the DCEP may

present great advantages to insurers in terms of risk and fraud

detection, though this depends in large part on the extent to which

PBOC data is shared with other financial institutions.

In light of the DCEP’s untapped potential, the 2022 Winter

Olympics in Beijing will — just like the 2008 Beijing Summer

Olympics — display to the world a modern, dynamic China with

its sight set on even further horizons.

Footnotes

1 In the words of Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland

President Loretta J. Mester, this would create “digital cash

[…] just like the physical currency […] but in a digital form

and, potentially, without the anonymity of

physical currency [emphasis added].”

The content of this article is intended to provide a general

guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought

about your specific circumstances.