Analysts believe that the Atlantic salmon industry could move away from net pen farming

©

AKVA

Norway’s salmon sector could be on the verge of adopting large offshore aquaculture structures while transitioning away from net pen production near the coast – at least if tech trends in the country’s development license scheme become reality. The development license programme was designed to address the industry’s economic and sustainability challenges by incentivising the adoption of new farming tech. Taking a closer look at the innovations approved under the licenses can give industry insiders a better picture of aquaculture’s tech future.

According to a new paper published in Aquaculture Reports, Norway’s salmon sector will likely embrace closed containment solutions and stronger offshore rigs as its main production methods. These innovations will help curb the negative environmental impacts of aquaculture by reducing farm emissions. They will also target larger production volumes, giving farmers a leg up on profits.

Norway’s Atlantic salmon industry

Atlantic salmon is the second-most valuable aquaculture species and Norway stands out as the commodity’s leading producer. Since the sector’s inception in the 1970s, salmon farming has become one of the most knowledge and tech-intensive segments in the wider industry. Norway’s industry also enjoys a high level of economic investment, allowing it to generate multiple sub-sectors that focus on salmon genetics, advanced health, nutrition and environmental sustainability.

Norway’s aquaculture industry is highly mechanised and producers are early aquatech adopters

©

Norcod

Though aquaculture advocates often tout its status as a low-emissions animal protein, farming activities still come with environmental and economic challenges. Atlantic salmon are usually farmed in open cages in sheltered inshore areas. Though this has let producers achieve incredible biomass volumes, open cages pose biosecurity and ecological risks. Pollution from faeces and feed residues have negatively affected local ecosystems, while fish escapes and sea lice interfere with wild salmon populations. Farming costs like labour and equipment are also on a steep upward trajectory, which could erode profit margins in the coming years.

To date, Norway’s salmon industry has relied on technological innovations to stay a step ahead of its ecological and fish health challenges. The country has also established a strong governance and regulatory structure for the sector. Environmentally sustainable practices are incentivised, and the structure helps spur the adoption of new farming technology. Norway currently stands out as an innovation hub – and seeks to maintain this status as consumer demand for farmed salmon grows.

Aquaculture development licenses

In 2015, the Norwegian government launched its development licence scheme. These licenses were different from regular commercial licenses – focusing on emerging tech instead of production volumes. The programme was designed to incentivise the development of new technologies that could help address aquaculture’s land use and environmental challenges. Designs and devices that could reduce sea lice levels, eliminate fish escapes and ameliorate pollution were given special attention. Disruption was the priority – improving on existing tech was not.

Closed containment systems could potentially reduce fish escapes, keep sea lice levels low and curb pollution

©

Reidun Lilleholt Kraugerud

The scheme sought to balance the economic demand for Atlantic salmon while mitigating its environmental drawbacks. Instead of having applicants pay for a commercial production license that could cost between $15 million and $25 million, applicants that successfully met the innovation and sustainability requirements of a development license could convert it into a regular production license for $1.1 million.

Regulators hoped that this would subsidise the industry’s innovation efforts. Having the sector fund its own research and development efforts wasn’t workable – meeting the moment required high initial investments and heavy technological and biological risks. In some cases, aquaculture’s innovation push was deemed “too risky” to court private investors. Development licenses were a way to overcome the limitations of the existing market.

What innovations are on the horizon?

The researchers reviewed over 100 applications for development licenses – paying special attention to the novel production methods, farm concepts and sustainability solutions that the applicants pitched. They noted that a large portion of development licenses were awarded for tech that made offshore aquaculture more feasible and methods that would reduce emissions from nearshore production systems. New measures that would mitigate fish escapes also received licences. This suggests that salmon production is moving in two separate directions: towards more robust open ocean cages and towards closed production units in the fjords.

The development license board reviewed designs for submersible net pens

©

Atlantic Subsea

The tech that received approval under the scheme shows that the development license board favoured larger aquaculture units. Enclosure volumes – and thus finished biomass – was scaled up from existing standards. Based on the approved licenses, the researchers believe that farming methods and equipment will become more heterogeneous. The current production model that has farmers putting a net pen in nearshore waters might not remain the industry standard. The researchers noted that the location of farm sites also played a significant role in the innovations under review.

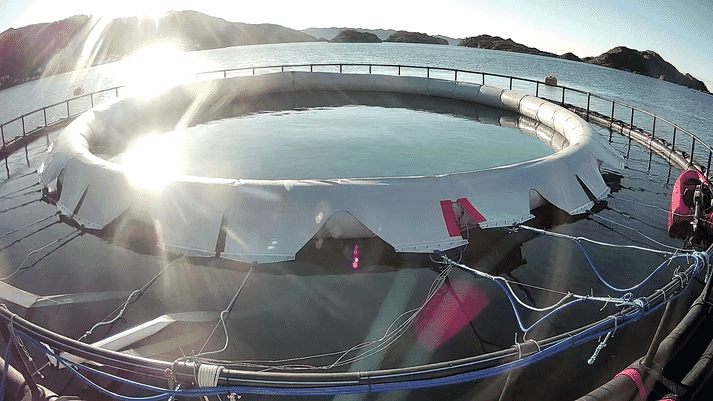

Technologies that received development licenses were geared for three main production locations: sheltered bays, coastal areas and the open ocean. Closed farms – or set ups that use bags or tanks as barriers against sea lice, escapees, pathogens and pollution from faeces and feed residues – were approved in sheltered and coastal areas. This means that firms operating in these environments will invest in tech that gives them a higher degree of control over the production environment. According to the researchers, this marks a pivot towards “biological manufacturing” – where producing fish becomes more akin to a biosecure assembly line. Open cage systems may fall out of favour in the fjords.

Closed containment designs were approved for use in sheltered and inshore areas

©

Nekkar

Projects for the open ocean prioritised innovations that let cages withstand increased loads from waves and currents. More than half of the development licence applications for this segment proposed semi-submersible platforms or rigid floaters with permeable nets. Given the success of these designs at the evaluation stage, the researchers believe that Norway’s regulator viewed these concepts as the most innovative. These cages also have a high biomass capacity – suggesting that the capital intensities and financial risks of these designs were a barrier for private investors.

The researchers noted that the emerging farm methods will require additional tech to be developed and deployed. Under-water feeding systems, integrated feed barges and heavy engineering solutions are necessary for aquaculture to thrive in this new stage – firms that can supply the tech could play a significant role in the industry’s growth.

These new farm methods will require additional tech to be developed and deployed to achieve their potential

©

EcoSea

The policy perspective

It appears that regulators are putting a greater emphasis on the seascape and ecosystem when they review potential aquaculture ventures. Standards are being adapted to reflect the different production considerations for the open ocean and nearshore environments. This suggests that regulators are willing to consider a greater variety (and cost) of production permits. However, this also means that producers could face additional requirements and oversight in the future.

The researchers believe that this regulatory stance has the potential to expand the marine areas that are available for aquaculture. It will also allow producers to test and adopt a greater variety of aquaculture production technologies. Farming new species could be on the cards as well. The authors point out that the new gamut of farming tech might be used for non-salmonid species – letting farmers diversify their aquaculture offerings.

For near-shore development licenses, regulators want producers to be less integrated with the external environment. Hence, the emphasis on barriers against fish escapes, the collection of fish waste and parasite prevention measures. Improving fish welfare is also a priority. In practical terms, this could mean greater reliance on farm tech and reduced manual handling.

Moving beyond Norway

Though these developments could usher in a more productive and environmentally sustainable salmon industry, it’s worth remembering that these concepts need to be economically profitable to interrupt the status quo. Given the salmon sector’s regulatory burden, profitability isn’t a given. Many of the concepts pitched to the development license board will take years to test and fully implement. Industry watchers may have to wait for innovation and economics to align.

The researchers stress that this kind of trend forecast can be expanded beyond Norway and the salmon industry. Most innovations will emerge in a few hubs before they spread to other fish species and producers across the globe. Aquatech solutions rarely stay in one place. If they are developed and adopted in Norway, it’s likely that they will be found in other aquaculture production areas within a few years – just adapted to local conditions and/or different species. Taking a closer look at Norway’s development licenses can give insights on what aquaculture’s future production technologies and priorities might be – and how the industry plans to achieve them.