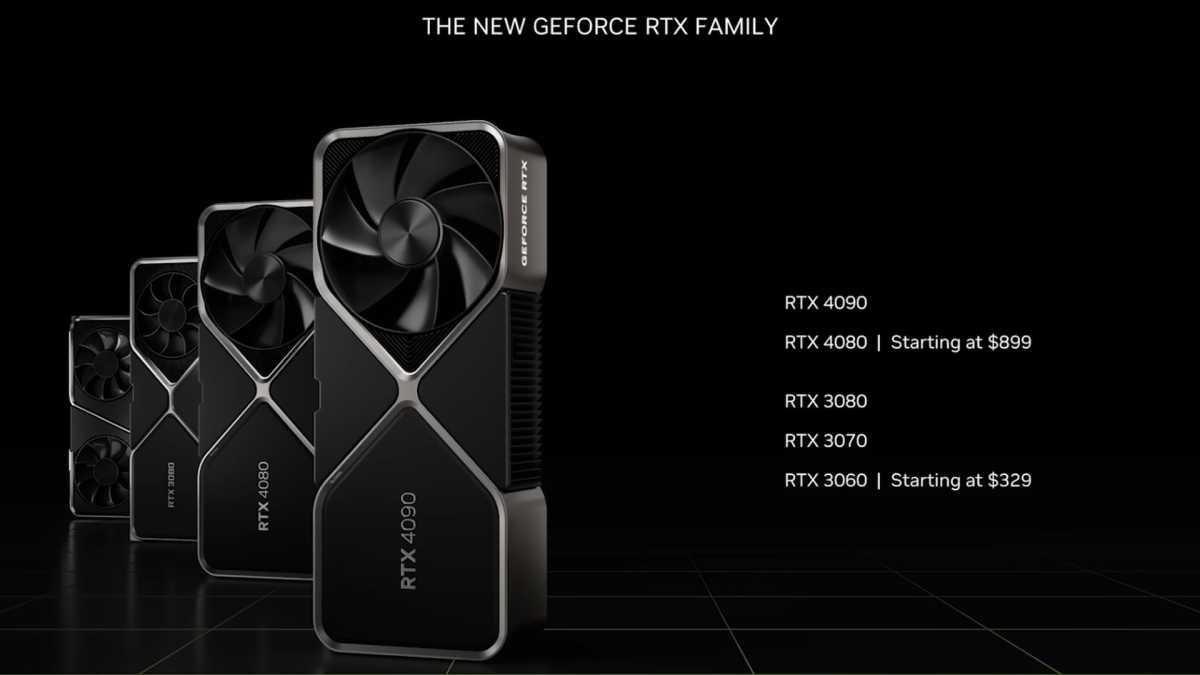

The world of PC gaming awaited the reveal of Nvidia’s GeForce RTX 40-series with bated breath, only to release a sigh of frustration at the end of Jensen Huang’s GTC presentation. The cheapest of the new cards is a whopping $900, a $200 increase over its predecessor…and thanks to some ambiguity in branding, arguably a lot more. Despite an effort to position the new RTX 4080 and 4090 graphics cards as merely the top-end of a new “GeForce family” that still includes RTX 30-series offerings, gamers are experiencing some serious sticker shock.

This is an opportunity for Nvidia’s competition, AMD and dark horse Intel. While AMD’s Radeon lineup has made absolutely amazing gains in performance and competitiveness in recent years, it remains a distant second in the market, with roughly 20 percent of discrete GPU sales. Intel, having missed the perfect entry point for its long-delayed debut Arc graphics cards during the GPU shortages of the pandemic, now has a second chance to present itself as a viable alternative to the duopoly.

Nvidia’s RTX 40-series pricing is a “new normal”

But let’s examine Nvidia’s position more closely. If PC gamers are groaning at Nvidia’s aggressive pricing, who could blame them? After two years of shortages during the pandemic, GPU prices were finally starting to normalize. With the worldwide chip shortage easing and the cryptocurrency bubble burst (and GPU mining allegedly “dead” to boot), we were sitting on a huge excess supply of high-end cards from both retailers and resellers. Anyone looking for a powerful GPU won’t have to look very hard, or spend very much, so long as they’re okay with core designs that are a little long in the tooth.

Nvidia executives claim that there are increased costs to these new GeForce RTX 40-series cards, that evolutionary technologies like the exclusive DLSS 3.0 make them more valuable, and that Moore’s law is dead…again, again. But those are statements more likely to win over engineers and investors than consumers.

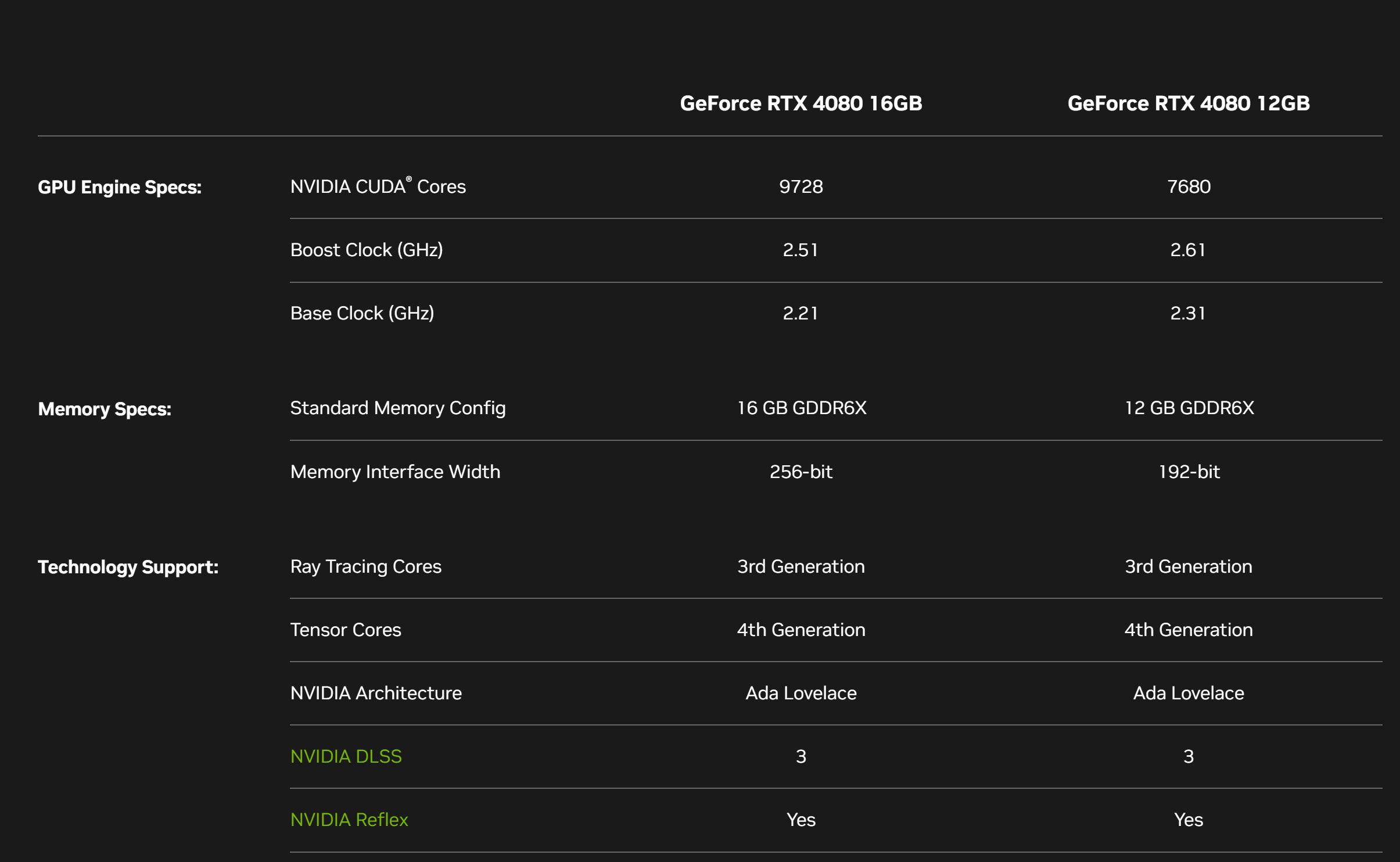

It doesn’t help that the new cards seem to be intentionally obfuscating some under-the-hood compromises. The new RTX 4080 comes in two varieties, a 12GB version for “just” $900 and a 16GB one for $1200. But despite the name, Nvidia has a novel and not altogether welcome approach to these tiers. The $1200 card is effectively a different, higher-tier Lovelace GPU, with 76 streaming multiprocessors instead of 60, almost 2000 extra CUDA cores, and a slight bump in memory speed.

Nvidia’s lower-spec version of the RTX 4080 could have been called the RTX 4070, but wasn’t.

Nvidia

Early observers are pointing out that Nvidia could have called the 12GB card the RTX 4070 if it wanted to. But there are obviously some branding advantages to giving the design a bit of a cachet boost…and a price boost to match. If you take the cynical view that the RTX 4080 12GB is an RTX 4070 under a more aspirational moniker, that gives it an effective retail price boost of $400 over the RTX 3070 from 2020. That might have seemed reasonable a year ago, now it just seems avaricious.

Nvidia can trot out core counts and benchmarks until the cows come home (and all those “DLSS ON” figures showing miraculous gains aren’t especially convincing, by the way), but the market is telling us that graphics cards should now be a hell of a lot cheaper than they have been for the last couple of years.

Nvidia’s counter to this is a shift in branding, the new “GeForce Family.” While older cards have always had a place in the budget market, Nvidia is now explicitly marketing the RTX 30-series as a cheaper alternative to the RTX 4080 and 4090, even though some of the existing “Ti” variant cards have retail prices just as high (or higher) than the new RTX 40-series GPUs.

Nvidia

The pandemic proved that people are willing to pay a lot more for graphics cards, at least under extraordinary circumstances. From a consumer perspective, it’s hard to see Nvidia’s pricing approach as anything except an attempt to keep that gravy train rolling. Nvidia appears to be using its dominant position to try and keep prices artificially high, strong-arming the GPU market into a “new normal” just as we were getting comfy with a return to sanity. It’s no wonder the peasants are revolting.

An opportunity to strike back

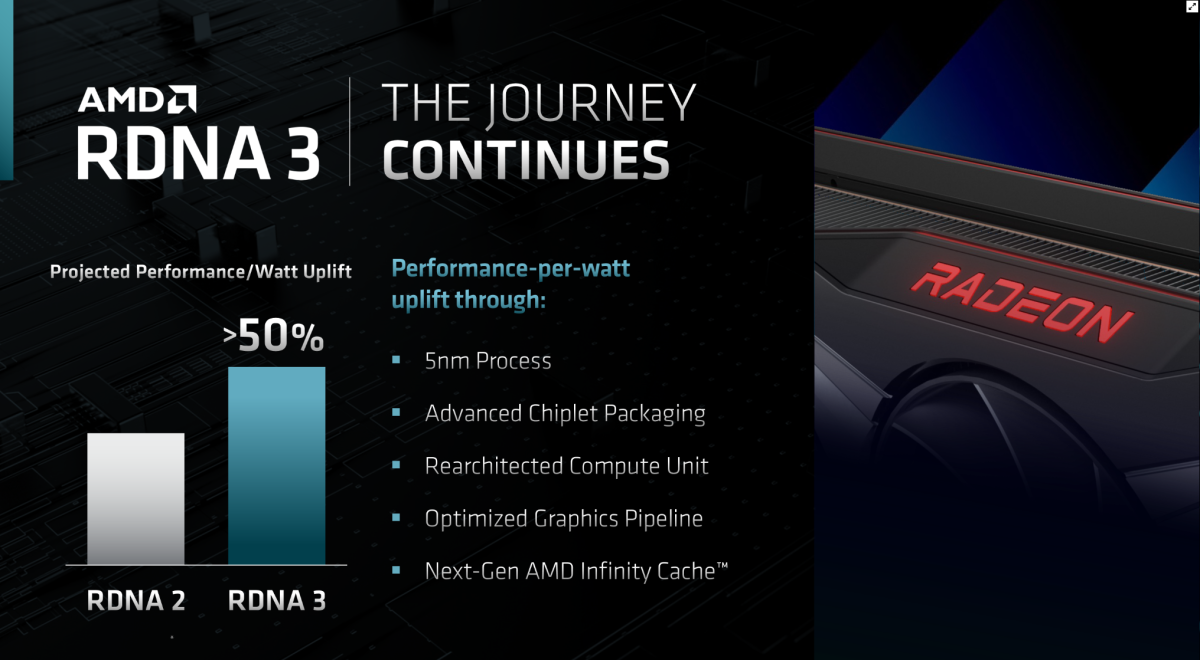

But with unrest comes opportunity. Nvidia isn’t the only company with a shiny new series of graphics cards on the horizon. As usual, AMD is preparing its next-gen offerings at more or less the same time — in fact the company announced the reveal of its next-gen RDNA 3 Radeon GPU family just hours before Nvidia’s CEO showed off his latest cards. It also indicated that AMD is thinking beyond the usual number-crunching arms race, targeting performance-per-watt gains that might just be welcome as energy prices rise even faster than everything else. But more intriguingly, AMD is expected to move to a chiplet-based approach with RDNA 3, eschewing the typical “giant monolithic die” approach, after successfully revitalizing the CPU market with Ryzen processors built around their own chiplet designs. GPUs and CPUs are very different beasts, but there’s the opportunity for RDNA 3’s chiplets to radically reset the graphics card market, depending on how they perform (and what they cost).

Intel

And don’t forget Intel. The company has been hyping up its entry into the discrete GPU market for more than a year, but frequent delays and less-than-impressive benchmarks for the debut Arc A380 graphics card have left us wondering when we’ll see anything except budget cards. Intel has been pretty frank about its troubles entering this incredibly competitive market, not least of which is a lack of experience in developing complex drivers. A full-range debut six months ago would have been perfect, but an entry at the midrange tier with the A770 next month is better late than never.

Intel knows it’s facing both a massive imbalance in experience and a market that’s unlikely to embrace a newcomer. And it appears to be making the smart choice: competing on price. According to interviews with the Arc development team, Intel plans to price its GPUs based on its worst-performing game tests. After Nvidia’s claims of triple and quadruple performance gains using proprietary rendering tricks, it’s a bit of refreshing honesty — assuming that actually pans out in prices on the shelf.

Right now, creating an unmistakable contrast with Nvidia is the smartest thing AMD and Intel can possibly do. With consumers experiencing almost unprecedented pricing fatigue, a possible recession looming to curtail expendable income, and sentiment poised to break against Nvidia’s attempts to keep prices high, there’s an incredible opportunity to exploit the market leader’s hubris.

AMD

AMD’s November Radeon RDNA 3 announcement will certainly show cards that are competitive with Nvidia’s designs, whether or not they can actually keep up with the RTX 40-series in terms of raw power. (However much that turns out to be, in the real world beyond ideal DLSS and RTX benchmarks.) Wherever the chips fall, AMD should absolutely hammer Nvidia with competitive pricing, especially in the mid-range.

Imagine the goodwill AMD could win if it reveals a theoretical Radeon RX 7800 that competes with the RTX 4080 12GB on paper, and beats a new RTX 4070 on price, coming in at around $550. That’s within striking distance of the retail price of the RX 6800 back in 2020. It wouldn’t be easy — inflation has hit hard in the intervening years, and the temptation to rise to Nvidia’s pricing will be strong. But positioning itself as an undeniable value would be an almost guaranteed way to grow market share, quickly and dramatically. It might even be worth positioning those cards at a loss leader price, at least while Nvidia insists that quadruple-digits is the new normal.

Brad Chacos/IDG

Meanwhile, Intel can double down on its promise to deliver value, clawing its way into the $150 to 250 segment with cards that can run most new games at 60fps without the ray tracing bells and whistles. Intel seems to understand that it simply won’t compete with Nvidia and AMD at the top of the market — that’s why its “flagship” GPU is under $350. Intel’s partnerships with OEMs (and, to be frank, its history of strong-arm business tactics) can be helpful here, delivering shelves full of prebuilt, inexpensive “gaming desktops” at retail stores around the world.

Selling competitive but not exorbitant cards to the budget-conscious doesn’t make you billions, but it does get you a seat at the table, and the opportunity to take bigger swings at the GPU market once your presence is established. Intel arguably has more to lose here; without some immediate, visible gains either in market share or in pure profit, its investors might get cold feet and tell the company to stick to tried-and-true CPUst Nevertheless, the opportunity is there — Intel wouldn’t have spent billions upon billions creating an entire generation of discrete cards if it wasn’t.

A fight for the future of the GPU market

Will AMD and Intel be aggressive enough to make the most of this situation, and tip the scales against Nvidia for the first time in decades? Who knows. I’m not telling these companies anything they haven’t already figured out for themselves, and I’m not privy to the kind of data that would even make those decisions possible. Despite a normalization of the chip market, it might not be economically possible to undercut Nvidia and remain profitable. And indeed, these companies might simply lack the business hutzpah to sacrifice short-term profitability in favor of the chance at a better position in the future.

But this kind of chance, this confluence of market circumstance and consumer unrest, doesn’t come along very often. If ever there was a time to knock Nvidia off its comfortable perch atop the GPU heap, it’s now. Even under ideal circumstances, AMD and Intel are unlikely to actually take away its huge lead in the market. But they won’t get a better chance to grab new customers anytime soon.