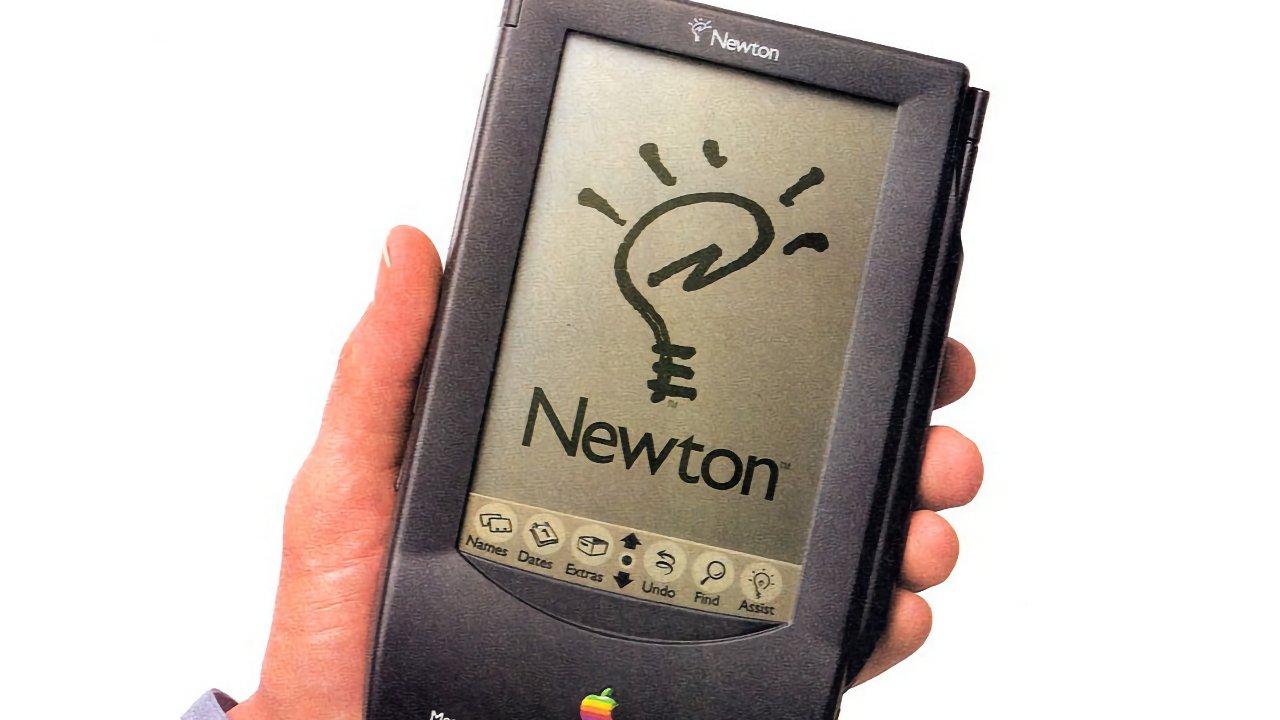

Apple’s Newton handheld computer was both the company’s biggest failure and its greatest peek into the future. Thirty years after launch, AppleInsider reminisces about what it was, what it meant, and where it went wrong.

Back in 1993, Apple’s press officers did the rounds of every technology magazine there was. When they reached one in London, they had the speech down pat. In particular, they knew how to fend off criticisms by asking questions first.

“What do you think it should have next?” they asked, subtly telling us more versions were coming and buttering up our egos. “Backlighting or color?” Without exception, the ten or so journalists in that office all said “backlighting” in unison.

It wasn’t a bad choice. Newton never would get color but it did get backlighting with the MessagePad 130 in 1996.

On reflection, though, the answer to “what does it need next” was a lot more complicated than a simple choice between two features. By the time we were being asked that, the device was already heading to failure because it was competing against everyone’s inflated expectations for it. Newton was announced so far ahead of being shipped and it was hyped so much that by the time it came, it was inevitably a disappointment.

That long delay also meant that competitors could at least start making rivals. Yet really the biggest rival to Newton had begun before the announcement. It’s just that it had been begun by Apple. At exactly the same time Apple was making Newton, its spin-off company General Magic was attempting to make a similar device.

It’s rare for a company to foresee where the future is going but Apple did it in the 1990s — and unfortunately did it twice at the same time. These were two separate Apple-backed devices that eerily predicted the world we live in today. And they both failed.

To understand where Newton went wrong, you need to see what it was trying to achieve before all of the hype and you need to go back further to the mid-1980s.

Who thought of Newton?

In 1985, Jean-Louis Gasse wrote that “in five years or less, computers will probably be capable of recognizing handwriting.”

In his 2023 biography, “Grateful Geek,” Gassee says it was when disaffected Apple engineer Steve Sakoman wanted to quit in 1987, that Newton began. Sakoman wanted to escape Apple’s politics, return to product creation, and work on his idea for a device with handwriting recognition.

“I should have given him a pep talk and pointed out that Apple was in great shape with many interesting projects ahead,” wrote Gassee. “Without thinking, I asked if he needed a CEO.”

They compromised. Sakoman agreed to stay with Apple and make this device only if his work would be kept free of interference.

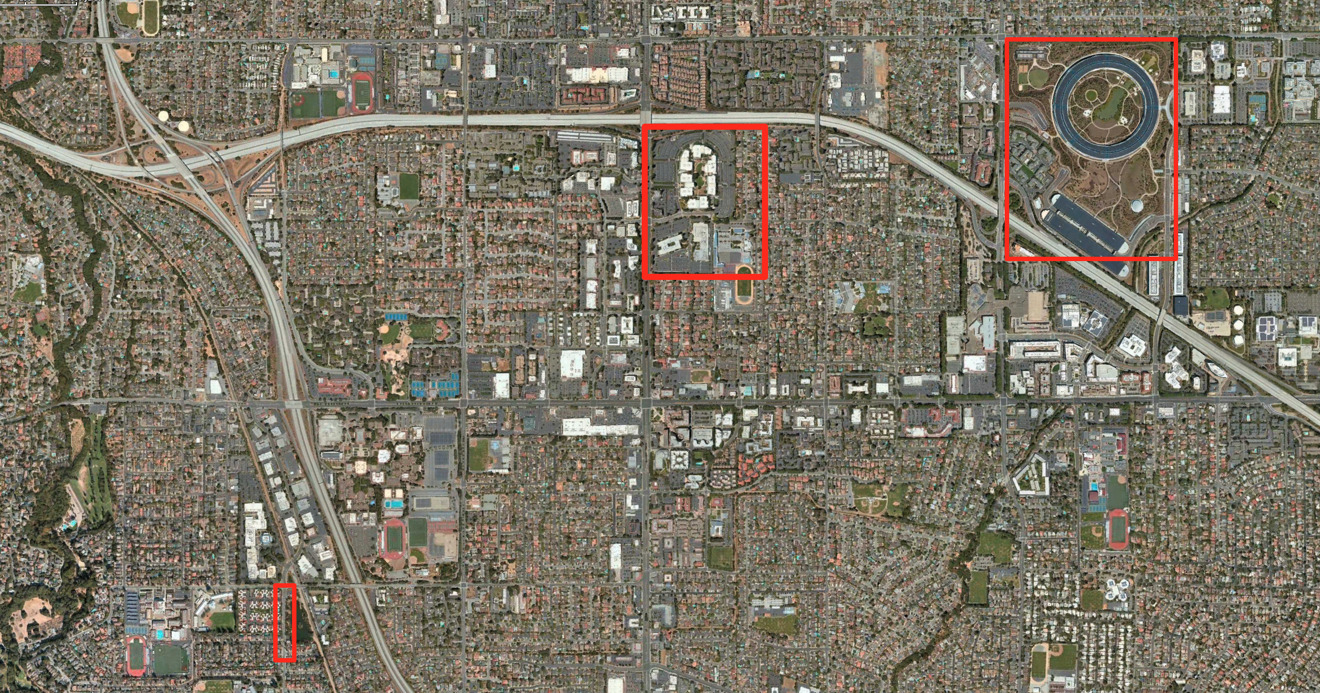

Gassee set him up in a building on Bubb Road, about ten minutes away from 1 Infinite Loop, and did not report to the Board what they were doing.

Sakoman wasn’t working alone, though. By this point he’d persuaded Steve Capps, co-writer of the Mac’s Finder, to return to Apple specifically for this project. What they and their team were doing was specifically to look at making a pen-based mobile computing device. By late 1987 Sakoman had named it Newton, after the original complex pen-and-ink Apple logo.

Also by this point, their plans or at least hopes were well developed. Newton was to be a handheld computer and communicator that sold for $2,495. That’s what the original Mac cost so it didn’t seem unreasonable. In today’s money, though, it’s $5,534 which does.

That’s $2,000 more than the Apple Vision Pro. Or it was. The planned Newton didn’t stay that price for very long.

It didn’t stay handheld, either: by 1989 Newton was instead on its way to being a tablet measuring 8.5 by 11 inches, codenamed Figaro, and probably due to cost between $6,000 and $8,000. Today that’s $12,193 to $16,257.

It’s not clear how long Gassee really did keep this project secret from the rest of Apple, but by 1990, the company’s Board definitely knew about it. By then, though, there didn’t seem such a need to keep it secret in order to prevent any interference.

That’s because Newton’s big supporter Gassee had first taken over worldwide product marketing and shortly after was also named President of Apple Products.

However, early in that same year, Gassee disagreed with John Sculley who wanted to licence the Mac operating system to other computer manufacturers.

Their difference of opinion and Sculley’s position meant that Gassee had a powerful title, but he was sidelined. It was a clear and significant enough change in Gassee’s position that he announced he would resign.

It was more internal Apple politics and this time, specifically because of how Gassee was being treated, Sakoman finally did quit Apple on on March 2, 1990.

That could’ve been the end of Newton except for Bill Atkinson. This is the man who was principally responsible for the Apple Lisa’s graphical interface which then became the Mac’s.

Atkinson invited Steve Capps plus Apple legends Andy Hertzfeld, Susan Kare, and Marc Porat to his home for a meeting on March 11, 1990. It was to discuss a way of keeping Newton going and, significantly, he also invited John Sculley.

Three years before in his now out of print book “Odyssey: Pepsi to Apple,” Scullley enthused about what he called the Knowledge Navigator. “Individuals could use it drive through libraries, museums, databases or institutional archives through various windows and menus opening galleries, stacks and more,” he wrote.

Sculley went a bit crazy for this idea, having Apple produce promotional videos for it.

Yet at that first meeting in Atkinson’s home, reportedly he just didn’t get it.

He did, though, ask for something that he could show the Board at their next meeting. If only by that request, Sculley got Newton going again.

With the exception of Steve Sakoman’s departure, the Newton team then began to return to normal. The Board approved the idea, Sculley gave Newton his official and full backing, and then he appointed Larry Tesler to run it in May 1990. There were just two things he mandated: Newton must go on sale on April 2, 1992 and it must cost $1,500 ($3,048 today).

This is where it gets odd

Marc Porat, who was at Atkinson’s March meeting, had been involved since a year before with a separate project to do with making partnerships with Apple and companies i the communications and consumer industries.

In May 1990, he and others persuaded John Sculley to spin off that project into the separate General Magic. Working for General Magic from the start were Porat, Bill Atkinson and Andy Hertzfield. At some point shortly after they were joined by Susan Kare.

So with the exception of John Sculley and Steve Capps, every person who’d been at Atkinson’s March 1990 meeting about the Newton was now with General Magic.

It’s a matter of record that General Magic had the kind of tight security and secrecy that we now associate with Apple. This year’s documentary about the company even shows some of the ways it implemented as total a blackout of news as it could.

Yet even if Apple did the same thing with Newton, so many of the General Magic people were ex-Newton that it is not physically possible that they didn’t know about their rival. These two companies aimed for the same goal of a handheld communicator that would revolutionize the world in pretty much the same ways and Newton announced first.

“John Sculley gave a keynote address at the Consumer Electronics Show where he announced what we were doing,” Andy Hertzfield says in the General Magic documentary. “Except he announced it as something Apple was doing. We thought Apple wasn’t doing it and we heard about it from that speech. We felt completely betrayed.”

“I thought they would co-exist. So I wasn’t really concerned that Newton would hurt General Magic. I was getting intense pressure from the Apple board and the Apple management team as to why I was spending so much time on General Magic [when] Apple was developing in parallel a business that it owned 100 percent of called Newton,” said Sculley. “And that looked like they could ship a product.”

It may have looked like it, but it wasn’t true.

When Sculley launched the Newton on May 29, 1993, it didn’t work. Literally. The first prototype demonstrated on stage wouldn’t switch on. Fortunately the second did. Even so, Sculley should not have caved in to pressure to announce it yet.

Ultimately, the Newton wouldn’t actually ship for another 14 months. It came out on August 2, 1993.

Its initial sales were good, for the time, with a reported 50,000 Newton MessagePads sold by the end of November 1993. However, whether through promotions or discounts, those were sold at $900 or $1,569 in today’s money, far below Sculley’s mandated figure.

The model shown to us in London was nowhere near as fast as using an iPhone today to make notes. However, it was faster than getting out your PowerBook was and the idea of having your calendar and emails with you all the time was compelling.

It just wasn’t the magical device we’d all been led to expect. When the handwriting recognition wasn’t perfect — and it often wasn’t — it got mocked.

That recognition did improve and the machine did get faster and it did ultimately get a backlight.

The end of the show

Newton subsequently went through eight versions of the hardware, and many revisions of its software mostly distributed on 3.5-inch floppy disk before Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997 and killed the project.

It didn’t actually get discontinued until 1998 and there were attempts by other companies to buy the technology but none worked out. To this day there are people using Newton MessagePads and a documentary was released about them and it this year.

John Sculley was ultimately the reason Newton came to market, and perhaps it’s because of acrimonious disagreements that Jobs killed it off. Yet it was also Sculley who created Newton’s most serious rival and it was he who announced it all more than a year before it could be made ready to ship.

“The Newton in 1998 looks remarkably unchanged from the Newton in 1993,” wrote Sculley. “With the exception that the handwriting now works and the screen is readable.”

If he’d let the designers get that right before announcing it, Newton might well have revolutionized the world. In an alternative reality, Newton could have been such a hit.

Which is what the writers of Apple TV+ hit “For All Mankind” think, too. That drama, which posits an alternative reality to our own, has characters using what’s actually a Newton MessagePad 120 with an iPhone 12 hidden inside it.

Even in our own reality, even just looking back at the history of the Newton, still we can see much of what made the iPhone popular so many years later.