Apple’s annual Worldwide Developers Conference isn’t as high profile as its iPhone launches. But, it has been the setting for moments that have radically changed the company — and all of our lives.

The iPhone, the iPad, and even the Apple Watch — none of them were unveiled at Apple’s annual Worldwide Developers Conference. Major new products get their own event, or they were announced when Apple would attend the now defunct Macworld conferences.

Yet every year since 1983 — albeit sometimes under different names — WWDC has kept developers and users up to date with Apple’s latest moves. That did include showing developers the Mac in 1984, but it had already been unveiled to stockbrokers.

A letter thanking a developer for attending 1983’s version of what would become known as WWDC. (Source: Apple Fritter)

Then 1986, the LaserWriter Plus printer was launched at that year’s precursor to WWDC. And in 1987, the Macintosh SE and the Macintosh II came out.

So in 41 years of Apple’s annual conference — and 35 years since it was named WWDC in 1989 — there have been only a few truly key moments. Whether it was a product launch, a strategy announcement, or just an exceptional speech, these are the WWDC moments that stand out in Apple history.

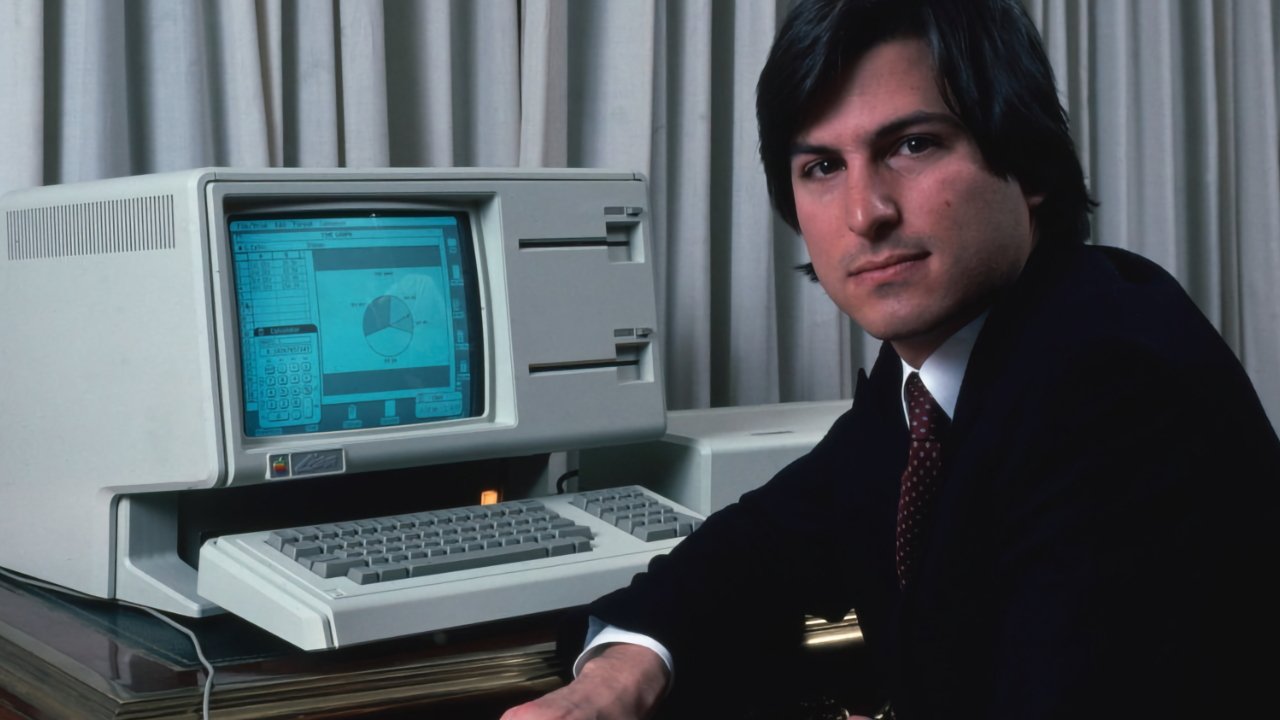

Best of WWDC – Steve Jobs’s fireside chat

There isn’t a fireside anywhere in sight, but this also wasn’t your usual WWDC keynote speech. Instead, in 1997, Steve Jobs briefly sat down before strolling about the stage, listening to an invited audience of acutely angry developers — and slowly talking them all around to his point of view.

Jobs had recently returned to Apple and one of his first acts had been to cancel an enormous number of projects. Some cancellations would upset users, such as the dropping of the Newton MessagePad, while others like OpenDoc would see developers steaming.

They’d spent years working alongside Apple and its aim to create a standard where developers could produce small utilities that then go together LEGO-style to make larger apps. Apple, Microsoft, IBM, and Motorola had been involved at various points, but it was Jobs who killed it.

You would think that a conversation, even a heated on, about an entirely failed software technology from nearly 30 years ago could not be interesting. You would think, too, that it could not relevant today.

Yet it is. This fireside chat remains remarkable, although chiefly because of how deftly Jobs spoke and it is a lesson in how to take really serious criticism and win people over through unflinching honesty.

“I was for putting a bullet in the head of OpenDoc,” Jobs told the developers. “I didn’t think it was great technology, but [also] it didn’t fit — the rest of the world isn’t going to use OpenDoc.”

“Apple suffered for several years from lousy engineering management, I have to say it,” continued Jobs. “Good engineers, lousy management.”

“And what happened was you look at the farm that’s been created with all these different animals going in different directions, and it doesn’t add up, the total is less than the sum of the parts,” he said. “And so we had to decide what are the fundamental directions we’re going in and what makes sense and what doesn’t.”

Bizarrely, though, if the details of OpenDoc and container applications are ancient and forgotten history, how he describes the use of technology is not. The technology that he spoke about then is still relevant today.

“I have computers at Apple, at NeXT, at Pixar, and at home,” he said. “I walk up to any of them and log in as myself… It goes over the network, finds my home directory on the server, and it just is, I’ve got my stuff wherever I am.”

Decades later, we can all do that — yet it still isn’t as smooth and transparent as Jobs described at WWDC 1997.

Best of WWDC – Hardware at WWDC

Today it’s a truism that the rumor mill will insist Apple is going to unveil hardware at WWDC, and then when it doesn’t, the same rumormongers say of course it didn’t. WWDC is a software conference.

Yet over the years, it has included some key hardware. Such as in the very first such event in 1983, when it was called the Apple Independent Software Developers Conference.

The name is unfamiliar but then the event itself was unlike any WWDC you’ve known. For a start, it did include the unveiling of the Apple Lisa — but according to some accounts, developers were asked to keep it secret for reasons passing understanding.

They didn’t do a very good job of it. A long-defunct magazine called Apple Orchard ran a two-page article about the conference, and included some snarky comments about the Lisa.

“A prime example of the kind of software that has yet to be developed for Lisa is a spelling checker,” it said. “Most of the material that was handed out at the conference was prepared using Lisalt contained several spelling errors… it was one more reminder that the imperfect human remains in control, but the tools continue to improve.”

Twenty years later in 2003, the Power Mac G5 was launched. It was accompanied by Steve Jobs’s typical enthusiasm — and even wolf whistles from the audience — but it was only after that launch that the significance can be seen.

This was the last PowerPC-based Mac and it was then the impracticality of putting a G5 processor into a laptop that helped push Apple toward using Intel. That’s despite Jobs saying about the G5 that, “we think it is the beginning of a whole new generation of architecture for Apple.”

Then, too, it was really this Power Mac G5 that introduced the “cheese grater” chassis. That would become more famous with the 2006 Mac Pro.

Best of WWDC – The move to Intel

After years of claiming that its PowerPC processors were faster than Intel’s — by famously comparing the Pentium to a snail — Apple did an about face in 2005. “Yes, it’s true,” said Steve Jobs at WWDC that year, “We are going to begin the transition from the PowerPC to Intel processors.”

“Now, why are we going to do this?” he continued, to laughter from the audience. “Didn’t we just get through going from OS 9 to OS X? Isn’t the business great right now?”

However, he said that “we want to be making the best computers for our customer looking forward.” Jobs talked about how Apple had not been able to deliver a faster G5 desktop Mac, or put a G5 in a PowerBook laptop.

“But these aren’t even the most important reasons,” he continued. “The most important reasons are that as we look ahead… we can envision some amazing products we want to build for you and we don’t know how to build them with the future PowerPC roadmap.”

Even back in 2005, he said that a key consideration what not just performance, moving to Intel would give Apple something else that was important.

“Just as important as performance is power consumption, and the way we look at it is performance per watt,” he said. “For one watt of power, how much performance do you get?”

Jobs then showed a chart that said over the next few years, PowerPC would give Apple “sort of 15 units of performance per watt.” He didn’t explain that unit, but he didn’t have to because “the Intel roadmap in the future gives us 70.”

“And so this tells us what we have to do,” he concluded.

Moving from PowerPC to Intel made possible the next 15 years of ever-improving Macs. It was only toward the end of that period that the same issues of limited potential began to make it clear that another move was needed.

Best of WWDC – The move to Apple Silicon

June 2020 saw a rather special WWDC. COVID restrictions meant that it was the first ever to be done entirely online, with a spectacularly well-produced video instead of the regular presentations.

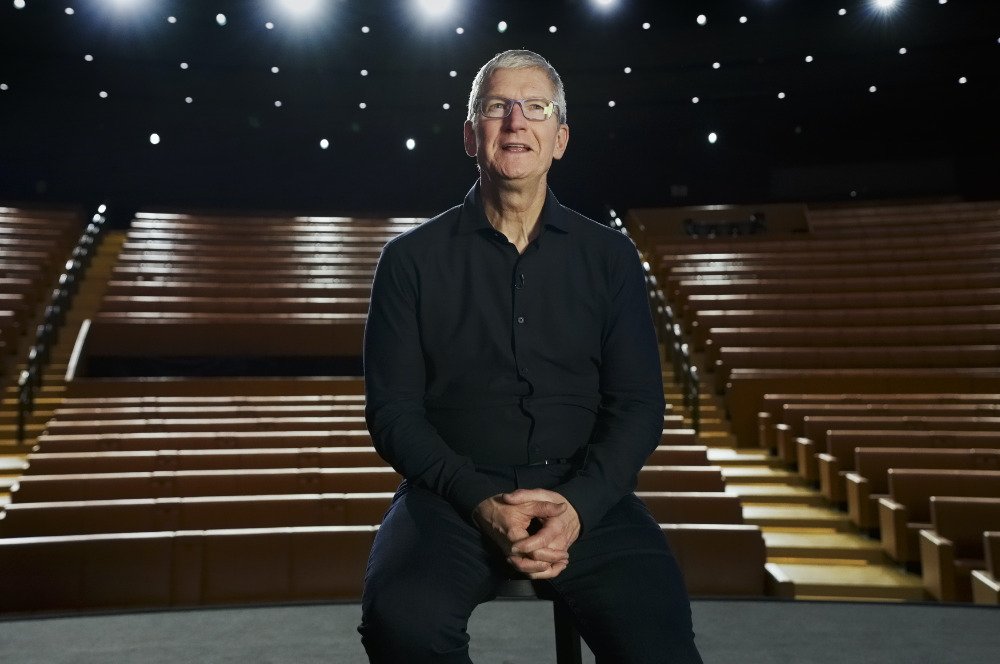

“Today is going to be a truly historic day for the Mac,” said Tim Cook in the event. “Now it’s time for a huge leap forward for the Mac, because today is the day we’re announcing that the Mac is transitioning to our own Apple Silicon.”

Now it was Intel that was limiting Apple, and now it was Intel’s future plans that were stopping Apple making the computers it wanted to. As early as 2011, it was reported that Apple had told Intel it needed to “drastically slash its power consumption.”

Apple went so far as to warn Intel it would move to another processor, and at times it was believed to be considering adopting AMD chips.

But something else had changed over those 15 years since the move to Intel, too. The iPhone.

Despite disagreements with Intel, Apple had asked it to make the processors for the iPhone — and Intel turned it down. “And the world would have been a lot different if we’d done it,” said Intel’s then CEO Paul Otellini said in 2013.

There’s at least a chance that if Intel had said yes to the iPhone that there would not have been a move to Apple Silicon yet. For one thing, Intel would have had to improve its power/performance capabilities, so some of the impetus for the move would have been reduced.

But it didn’t say yes, then it didn’t improve its power/performance, and ultimately Intel began producing only better and better PowerPoint presentations about the processors it would make some day.

Tim Cook in front of a spookily empty Steve Jobs Theater at WWDC 2020, when he announced Apple Silicon

Plus having lost Intel for the iPhone and instead decided to design its own processors for that, Apple gained enormous experience in processor design overall.

Now Apple could do it all itself — and Apple likes to do everything itself, or at least everything that it possibly can. It’s called owning the whole stack, and Apple does that more than any other computer firm.

Apple designs the operating system, it manufactures everything it can from the motherboards to the casings, and now it was designing processors too. And now it was designing them very well.

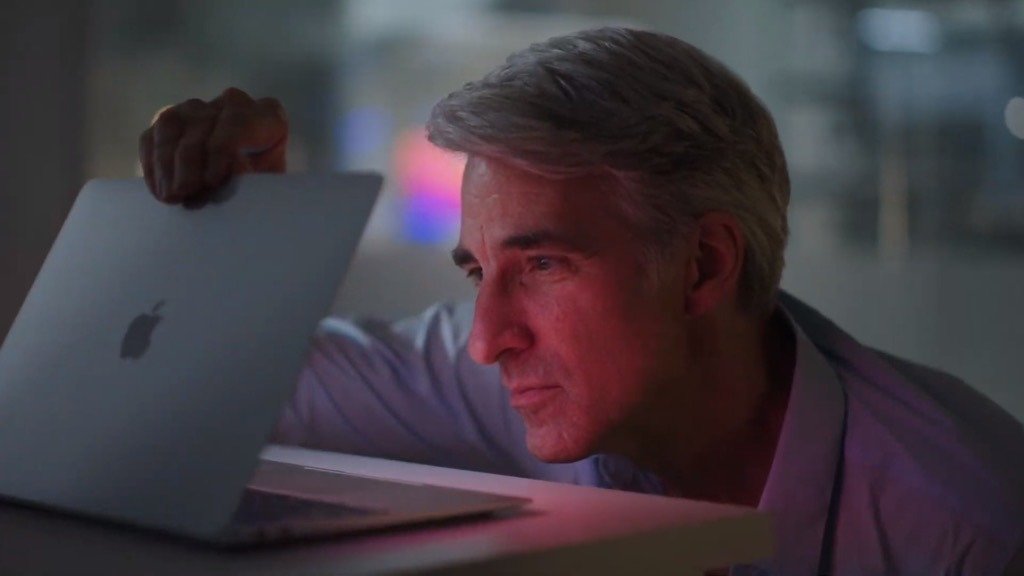

“We overshot,” Craig Federighi said of Apple Silicon in 2020. “You have these projects where, sometimes you have a goal and you’re like, well, we got close, that was fine’.”

“This one, part of what has us all just bouncing off the walls here – just smiling – is that as we brought the pieces together, we’re like, this is working better than we even thought it would,” he continued.

That was to do with the performance of the initial Apple Silicon tests, but of course Apple was still also focusing on power/performance. And Federighi said that had turned out to be even more unexpected.

“We started getting back our battery life numbers, and we’re like, you’re kidding,” he said. “I thought we had people that knew how to estimate these things.”

Borrowing from Steve Jobs

Apple got rave reviews for its move to Apple Silicon, but in general it is rarely credited for how it manages transitions like these. That’s partly because no one else has done it — Microsoft keeps trying to move Windows to ARM processors.

But it’s also because Apple has made it easy. It made the move from PowerPC to Intel so smoothly that when he came to announce Apple Silicon at WWDC 2020, Tim Cook followed exactly the same playbook as Jobs had done at WWDC 2005.

Cook explained how this move was not going to happen overnight, and he even echoed Jobs’s line about more PowerPC devices to come by saying there would be more Intel Macs. There weren’t, as it happens, but he was telling developers that the transition would be smooth.

And it was developers he had to tell first, so it was WWDC where he had to announce it.

Four years on, the move to Apple Silicon is behind Apple and we’re not going to see another hardware transition this year. Yet WWDC 2024 may yet come to be seen as another key year for the conference.

For it is as close to certain as it can be, that Apple will make major AI announcements for the Mac and iPhone on June 10, 2024.