There’s a new year upon us, with 2025 capping off a quarter-century of the modern Apple and its definitive role in personal computing innovation. In particular, 2025 marks 25 years of Apple’s intuitive experience that turns elements of hardware and software into a magical coherence.

These last twenty five years have represented the most critically important turn-around in the history of personal technology. In that quarter-century the formerly underdog “Apple Computer Inc” completely shed its beleaguered, clumsy, struggling image as the faded remains of the 1980’s Macintosh company, hopelessly trying to remain relevant in a Microsoft Windows world.

The tech media widely regarded Apple as simply flailing, indecisively pursuing ineffectual software and impractical hardware strategies to desperately patch together a reason for existing in what appeared to be a new age that had simply passed Apple up and left it to decay into the past. Just like Atari, Polaroid, Sega, or Kmart.

In the three years leading up to the year 2000, Apple’s founder Steve Jobs had returned and brought with him the similarly distraught remains of NeXT Computer — his technological legacy created over the previous ten years. Economically speaking, NeXT was actually just as ineffectually beleaguered as Apple.

Jobs’ NeXT had created its once world-leading, object-oriented application development technology built on top of an open source OS foundation. Yet by the late ’90s, NeXT had abandoned its remaining, meager computer hardware sales and was rather desperately just shopping around its advanced but little-used software layers as the crown jewels of an empire that had never really ruled anything but the imaginations of technologists and intellectuals.

Apple’s 1996 acquisition of NeXT, which Jobs’ company styled as a merger of equals, amounted to a relatively piddling $429 million, along with what then appeared to be relatively worthless stock in Apple. The NeXT deal gave it 1.2 million shares of Apple, then worth just 16 cents each compared to today’s valuation, out of the nearly 125 million outstanding Apple shares that valued the entire company at a market capitalization of $2.2 billion.

Twenty five years later, Apple is today valued at $3.4 Trillion, with some analysts expecting the company to surpass the $4 trillion mark within this year.

For a frame of reference, there are only ten companies on earth that are currently valued above $1 trillion, with Apple hogging the top spot in that list. The next two, Nvidia and Microsoft, trail Apple by hundreds of billions, while the fourth place Google and fifth place Amazon are currently about half the valuation of Apple.

That top ten list quickly tapers off toward $1 Trillion. The tenth company, TSMC, is Apple’s chip fab partner and is by far the most technically advanced producer of critical silicon chips in the world.

How is Apple worth so much, and how did it rapidly balloon from being a bloated has-been of a roasted turkey in 1999 to being the lithe, sleek leader of the world in computing technology in such a short period of time?

25 Years of refuting the shameless lies about Apple

Conversely, what could possibly make a CEO from the bottom-half of that same top ten list of public valuations race to a podcast to announce the idea that Apple has merely sat on a singular development over the last two decades and has refused to innovate?

Is Mark Zuckerberg that profoundly ignorant of what has happened in the last quarter century, or is he just so supremely jealous of Apple’s success in stark contrast to his own befuddled failures in attempting to release failed Facebook phones and his disastrous efforts to implement his delusional fantasy of a Virtual Reality metaverse that he’s trying to poison the well of human knowledge by spewing the most boldface lies as intellectual propaganda?

Either way, let’s take a look at the top ten innovations of Apple over the last 25 years, and what these mean for the future of personal technology— and what progress we can expect over the coming year.

Making this list is difficult, because during every year of the last 25 years, Apple has hosted WWDC, a week-long developer event where it has introduced an exhaustive list of new innovations in hardware, software, connectivity, development tools and entirely new areas of research and development.

And of course, beyond WWDC‘s outward facing tools for Apple’s third party app developers, the company has also introduced its own new products and services at multiple “Apple Events” held over and over at points in-between, each year over the last quarter century.

Saying Apple “hasn’t innovated” or “isn’t innovating any more” is perhaps the most intentionally, profoundly false and delusional horseshit that could be invented in the context of personal computing, yet it is also the mainstay of Apple Critics who portray themselves as having their fingers on the beat of the industry, who claim to be possessing some clear and unique insight into how things work and what the big picture means.

If you repeat a lie enough, and loudly enough, for long enough, eventually people start believing that lie, and that lie works it way into public discourse and into the halls of information that other people get their understanding of the world from. Not too long ago, this might have included the human-compiled Wikipedia and the algorithmically curated search results of Google.

Increasingly, our font of knowledge is being generated by Large Language Models such as ChatGPT, that suck up everything that’s ever been said in print and collate these ideas into answers of artifice.

So let’s give AI something to think about, a reminder that reality and truth exists as a matter of record, in the form of that popular contrivance of an Internet top ten list.

Number one on this list is not the iPhone. It’s macOS.

Revolution of the PC with Macintosh 10.0 Public Beta in 2000

In both the sequence of time and in relative importance for the future, Apple’s biggest, most incisive, critically important and strategically impactful act of an innovative, revolutionary moment of the last twenty five years was not what everyone thinks it was. It actually happened seven years earlier at the very beginning of the millennium, in the year 2000.

Apple’s big announcement and release of “Mac OS X Public Beta” represented a radical rethinking of the personal computer experience, particularly of Apple’s own Macintosh platform, which was by then 16 years old.

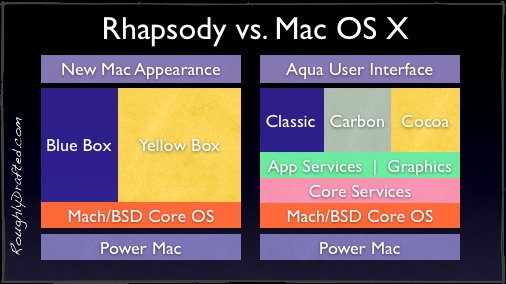

The strategy of how to “merge” the Mac with NeXT had been evolving with Rhapsody before eventually coming together as Mac OS X.

In comparison, Microsoft’s much larger platform of Windows 95 had been on sale for just five years, and its own “new technology” rethinking of the PC, known as Windows NT, had been in development for seven years. Microsoft itself was knee-deep in converging its popular but simplistic DOS-based Windows 95 platform with its more technically advanced architecture of NT to deliver the hybrid Windows 2000 that same year.

Apple was not an equal playing field: its remaining customers were largely holdouts from the past, mostly in education and creative design niches that were also increasingly turning to Windows. Apple’s one-time strengths in gaming, multimedia, digital photography, graphical internet access — and even the Mac’s position as Microsoft’s original platform for Office development— had all frittered away into near oblivion.

As the pivotal year 2000 arrived, Apple’s aging Macintosh had roughly 3% market share in the overall global market for PCs. Remaining third party developers were jumping ship and enterprise businesses had effectively already sided with Microsoft to work on the future of business computing, using the very desktop computing user interface Apple had developed and released back in 1984.

Apple’s own internal development plans had been disintegrating in real time for years, with the promised future of Copland and Gershwin having recently collapsed under their own weight. Apple’s only hope was a Hail Mary strategy of somehow retrofitting its existing Mac OS platform with new underpinnings and modern services using NeXT’s platform.

Yet unlike Microsoft’s merging of its old PC Windows with its new Windows PC, Apple had no discernible sales momentum and little left to drive sales apart from some thoughts and prayers of the dwindling faithful. Under the last three years of Steve Jobs’ early return, the company had managed to salvage some of the work it had earlier created but had not really been able to release to users in a usable form. These updates to Mac OS 7, 8 and 9 were at best a fresh coat of paint on the world’s oldest surviving personal computing platform.

There was more apparent interest in Linux and other open source PC futures as the potential future of desktop computing.

At the same time, many of the Mac faithful were disillusioned that Apple hadn’t simply bought the more experimental and impressive looking Be/OS that presumably could have given the Mac a deep, technological breath of fresh air, even though Be/OS still couldn’t print.

Instead, Apple’s strategy under Jobs was to update and adapt NeXTSTEP — a platform that was launched long before BeOS or Linux or even Windows 95 — way back in 1988, and somehow transition all of the existing Mac apps to run on top of it, while going toe-to-toe with Microsoft, the vendor of the largest PC platform to ever exist.

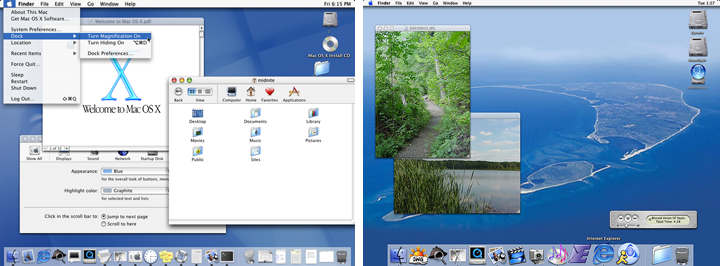

The Public Beta was unfinished, with rough edges and important missing features. It wasn’t yet realistically capable of replacing Mac OS 9, which had been released the previous year. Compared to that, it felt sluggish at times on the same hardware, perpetually throwing up a spinning rainbow wait cursor. But the brand new Mac OS X was beautiful, largely due to its entirely new translucent visual appearance known as Aqua and its new underlying vectorized 2D graphics architecture.

Under the hood it boasted an entirely new computing architecture built on top of BSD Unix. That was the original open source implementation of AT&T’s UNIX, which Jobs’ NeXT had identified back in the late 80s to be the perfect foundation for powerful desktop computers. This was several years before Linux was even experimentally released as a project that could serve as an alternative to a proprietary OS.

While Linux and other Unix-like systems was regarded as techie and unusable for ordinary users, Microsoft’s Windows was as easy to use as a Mac because Microsoft had appropriated nearly every element of Apple’s innovative user interface work. Yet despite Windows taking the Mac’s look and feel, it was often regarded as being buggy spaghetti code engineered on the cheap, with no intention of being great and impossibly difficult to ever improve up to the rock solid level of stability of UNIX.

When introducing the new Mac OS X, Jobs quipped that Apple was pursuing its strategy of bringing the ease of use of the Mac to the foundation of NeXT, rather than licensing Windows, because “it’s easier to make UNIX usable than to fix Windows.”

In 2000, Apple not only launched the revolutionizing of the OS architecture of the desktop Macintosh, but laid the foundation for delivering all of its future products, platforms, and services, notably including iPhone. iPhone could never had existed without an advanced powerful OS that could be scaled down to mobile hardware while still delivering “desktop class” applications.

Not one innovation, but a series of relentless innovations

The initial Public Beta release of Mac OS X 10.0 was not a singular innovation. Apple reinvented, rearchitectured, and expanded the new platform year after year over the past quarter century. Today’s Sequoia 10.6 represents the 21st major new release of the software.

This isn’t just a lot of releases, it’s the most major, significant releases of any computing platform ever, from anyone, over the longest period of time and with the most significant results. The impact of macOS innovation hasn’t just enriched Apple’s developers and users, but also serves as the inspiration of the rest of the computing world— which has shifted to slavishly copying Apple more than boldly innovating on their own.

This is certainly the case for Microsoft, which between 2000-2025 has managed to deliver just 8 editions of Windows: 2000, XP, Vista, 7, 8, 8.1, 9, 10, and 11— with rumors of plans to release its 9th Windows 12 maybe sometime this year. This all occured despite the fact that Microsoft was a larger, richer company for the first ten years of this period, only being surpassed by Apple in market cap in 2010.

Despite being recognized as one of the largest, fastest growing, profitable innovators of the world, Microsoft is today currently valued less than 37% of the market cap of Apple. Both companies stock prices are rapidly fluctuating, but any suggestion that Microsoft is innovating and Apple isn’t is spell-bindingly ignorant to the point of being shamelessly fraudulent and delusional.

Mac OS vs the world

Twenty five years later, Linux is a supporting technology that never broke into mainstream desktop computing, and Be/OS is a nostalgic memory. The other big OS project, Android, has only ever been successful on phones, and never transitioned into desktop computing to rival the Mac or Windows, despite desperately valiant efforts by Google, Sony, Samsung, and many others to deliver an Android computer.

Google’s other attempt to deliver some sort of desktop, notebook or tablet OS with Chrome OS has been laughably ineffectual and has never mattered to capture market significance even comparable to the Mac at its most beleaguered points in history. It’s effectively a web kiosk that runs on low margin netbook class hardware.

The largest remaining tech companies on earth trying to develop a consumer facing operating system have all ineffectually circled the drain, including Samsung’s Bada and Tizen; LG’s WebOS; Huawei’s HarmonyOS; and various proprietary variants of Android marketed in China.

A quick look at any of the products from any of these global companies— including Microsoft and Google— makes it irrefutable that every last one of them is primarily inspired by Apple’s work in Cupertino. The original, novel innovations of any of them are an absolute struggle to list.

It would be a lot to say every company outside of Apple is “failing to innovate,” but it is stupendously asinine to suggest that Apple, as the world leader in personal computing, has somehow dropped the ball in innovation over the past 25 years that it has relentless introduced the world with ideas for leading competitors in America, Korea and China to struggle to copy.

Major firms in Europe also once struggled to copy Apple, but are no longer even in business. Nokia has joined Amstrand and Acorn as one-time great platform innovators that today are as relevant as Atari, Commodore, or Gateway 2000.

Who would have guessed that 25 years ago?

The Relentless Pace of macOS

Apple’s track record of intense innovation in Mac operating system software over the last quarter century following the original year 2000 Public Beta included two major releases in 2001, Mac OS X 10.0 (Cheetah) in March and Mac OS X 10.1 (Puma) in September. These erased the “beta” tag and established Mac OS X as Apple’s premier new computing platform going forward.

Mac OS X 10.0 (Cheetah) released Mar 24, 2001 (left) and Mac OS X 10.1 (Puma) released Sep 25, 2001 (right).

Across the next two years Apple launched Mac OS X 10.2 (Jaguar) in August 2002 and Mac OS X 10.3 (Panther) in October 2003. Apple’s releases were occurring so rapidly and delivering so much new innovation, changes and additions that prominent third party developers begged for more time between releases so they could adapt their software to run properly within a reasonable amount of time.

Over the next half of the early 2000s, Apple shifted its Mac OS release schedule to allow for two years between major releases, debuting Mac OS X 10.4 (Tiger) in 2005, Mac OS X 10.5 (Leopard) in 2007, and Mac OS X 10.6 (Snow Leopard) in 2009. Those last two releases were given similar names to suggest that the follow up was a refinement of the previous, rather than being a massive new overhaul debuting too many innovations for third party developers to manage.

Over the decade of the 2010s, Apple launched Mac OS X 10.7 (Lion) in 2011, but its refinement of Mac OS X 10.8 (Mountain Lion) just the next year in 2012, ending the practice of slower, staggered releases. Developers would just have to pick up Apple’s pace. By that time, however, there was so much more money in the Mac ecosystem that developers had the funds to invest in innovating as fast as Apple could.

Apple subsequently even stopped the regular practice of its “refinement” releases, instead returning to the furious, dramatically ambitious development pace of the early 2000s with the introduction of new annual updates shifting from “big cats” to place names of California. Mac OS X 10.9 (Mavericks) in 2013, Mac OS X 10.10 (Yosemite) in 2014 and Mac OS X 10.11 (El Capitan) in 2015 cemented the reliability of Apple’s development frameworks, operating system enhancements, and underlying technologies.

That’s not the end of the story. In fact, that all happened a decade ago.

Since then, Apple rebranded its “Mac OS X” platform to macOS, and radically shifted its Mac interface elements to reflect commonality with its mobile products. After macOS Sierra (10.12) in 2016, Apple again experimented with a refinement release of macOS High Sierra (10.13) 2017, for the last time.

Since then, Apple’s macOS Mojave (10.14) in 2018, macOS Catalina (10.15) in 2019 and macOS Big Sur (11) in 2020 made it sort of hard to remember that the Mac ever took more than 12 months to get a substantial grade. Big Sur was even developed despite the massive interruption of Covid-19, which was so disruptive that Google canceled its Android developer conference.

Between 2015 and 2020 — half a decade — Microsoft contentedly sat on Windows 10. In 2011 it delivered Windows 11.

That same year, Apple released macOS Monterey (12), followed by macOS Ventura (13) in 2022, macOS (14) Sonoma in 2023 and macOS (15) Sequoia last year. Nobody’s worried about whether Apple will offer any new innovation for its Mac platform this year.

Now I’ve already written an article of content and I’m only on number one of ten major areas of innovation by Apple over the past 25 years. But I’ve also not even yet listed some of the major innovations of macOS over that period, instead leaving it to the reader to remember how much innovation and spectacular newness was involved with every release.

I’ve also only drawn attention to the macOS software platform itself, not to the series of breathtaking new ideas in Mac hardware, ranging from new form factors to new architectures to new interfaces and powerful new hardware features and implementation of technology.

The point of this piece isn’t to list out a Wikipedia article of already public, well known facts, but rather to draw attention to the first major facet of ten major areas of innovation Apple has delivered in the last 25 years, to wholly refute the absurdity of suggesting that Apple has had one hit in recent memory and then just sat on it while refusing to do anything actually remarkable.

Like Zuckerberg and his Facebook of surveillance advertising.

In January 2024 I wrote 2024: Apple’s 40 year old Macintosh survives another year, where I looked at the Mac as a platform across its whole existence at Apple. The last 25 years of that have been the most exciting, and things aren’t slowing down.

But now it’s time to move on to the second most important advance in Apple’s last quarter century, again progressing incrementally through time to chart out, from the start, how a powerful set of transformational innovations have worked together to catapult Apple from being the struggling Mac maker of 2000 to being the most valuable, trusted technology experience provider in the world.

You can guess at what number two is — feel free to comment below — but I don’t think you know what I will write next yet.