In terms of SIlicon Valley feuds, you’d be hard pressed to find one that’s spicier than the years-long battle between Meta and Apple. Meta Platforms CEO Mark Zuckerberg started steering his company towards virtual reality tech, and now Apple CEO Tim Cook has made it clear he’s gunning for the same. Meta’s Facebook recently started testing out encrypted chats, a domain that Apple has dominated for years.

Facebook is a company that historically hasn’t shied away from sharing user data with countless third parties. Meanwhile Apple

AAPL,

as its own glitzy ad campaigns constantly remind us, is the one tech company that doesn’t spray your data across the web. And of course, there’s Apple’s recent privacy changes to its operating system that wiped an estimated $10 billion off Meta’s

META,

market cap. At the same time, the advertisers that relied on the long-established tools on Facebook and Instagram were left without the data they long relied on for their businesses.

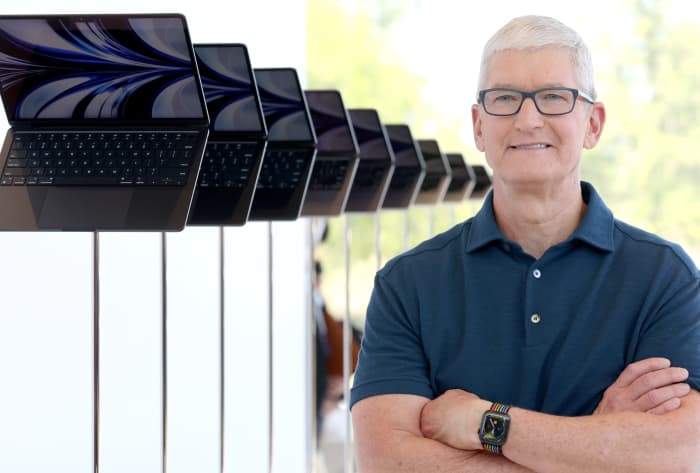

In the year since Apple CEO Tim Cook denounced ad-based business models as a source of real-world violence, Apple has ramped up plans to pop more ads into people’s iPhones and beef up the tech used to target those ads. And now, it looks like Apple’s looking to poach the small businesses that have relied almost entirely on Facebook’s ad platform for more than a decade.

Marketwatch found two recent job postings from Apple that suggest the company is looking to build out its burgeoning adtech team with folks who specialize in working with small businesses. Specifically, the company says it’s looking for two product managers who are “inspired to make a difference in how digital advertising will work in a privacy-centric world,” who want to “design and build consumer advertising experiences.” The ideal candidate, Apple said, won’t only have savvy around advertising, mobile tech, and advertising on mobile tech, but will also have experience with “performance marketing, local ads or enabling small businesses.”

The listings also state that Apple’s looking for a manager who can “drive multi-year strategy and execution,” which suggests that Apple isn’t only tailing local advertisers, but it will likely be tailing those advertisers for a while. And considering how some of those small brands are already looking to jump ship from Facebook following Apple’s privacy changes, luring them off the platform might be enough to hamper Meta’s entire business structure for good, adtech analysts said.

“If you talk to any small business, they’ll tell you ‘yeah, right now is a disaster,” said Eric Seufert, one such analyst who’s been following the battle between Apple and Facebook evolve for years. “It’s just a meltdown. There’s been a complete, devastating change to the environment.”

‘What goes around comes around’

Is Apple’s Tim Cook stealing a page from Facebook’s playbook?

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Zuckerberg has said (over and over again) that Apple’s move to cut off the company’s precious user data would hamper “millions” of small businesses, and indeed, in the iPhone update’s aftermath, some marketers said they were left “scrambling” to measure who their ads were reaching–and typically paying sky-high prices for the privilege to do so.

From an iPhone owner’s POV, it can be tough to understand exactly how a privacy feature can singlehandedly bring countless mom-and-pop’s to their knees. Especially when that feature, App Tracking Transparency (ATT)–which Apple rolled out in April of last year–does something as upstanding as mandating that app developers give users the freedom to choose whether or not they want to be tracked across their device.

Most of those users, by all accounts, would end up saying no. And when they did, those apps lost access to a crucial mechanic in mobile advertising; that person’s unique “identifier for advertisers,” or IDFA for short.

You can think of it as something like the iPhone’s answer to a web cookie: an advertiser can use your IDFA to track, say, whether you saw their ad on Instagram and then bought their product on Etsy, or followed their account on Pinterest. IDFA was the key that let mobile advertisers know whether their ads actually worked.

So when Apple’s change hit, it wasn’t just Facebook’s advertisers that were flying blind–small shops that were running ads on Google’s

GOOG,

YouTube, Snap’s

SNAP,

Snapchat, Pinterest

PINS,

and any other platform where fine ads are sold felt some sort of the hurt. And the more your platform relied on user data for your business, the bigger sting you felt.

“You can have an ideological take on all of this and say ‘well, these ad tools shouldn’t have gotten so efficient, since that was dependent on violating people’s privacy,” Seufert said. “And that’s a fair argument!”

But as he also pointed out, you can’t ignore economics. Apple certainly isn’t.

“I guess what goes around comes around,” said Zach Goldner, a forecasting analyst at Insider Intelligence who specializes in digital ads. “I mean, it’s not like Facebook hasn’t copied other platforms before.”

Aside from its myriad privacy scandals, the other core concept that the Meta brand is synonymous with is copying its competitors. As Goldner put it, it was only a matter of time before someone tried dethroning the company that’s spent more than a decade making its brand synonymous with small businesses.

“Using Facebook ads for small businesses is voluntary in the same way that using email for a job search is voluntary,” said Jeromy Sonne, a longtime digital marketer who has since abandoned the platform to start up his own ad-serving network.

“No, you’re not ‘locked in,’ and they aren’t forcing you to spend money. There’s no contract here,” he went on. “But because of the lack of options and the number of businesses that built their entire revenue off the back of the platform, it’s virtually impossible to walk away.”

How Facebook became ‘virtually impossible’ for small business to escape

Mark Zuckerberg made Facebook indispensable for the nation’s small businesses. Will his stranglehold on them last?

AP

Before rivals like Snapchat and TikTok would hit the social media sphere, Facebook had already been running ads for years.

Some of the last holdouts in the switch to digital were smaller businesses–and reports from the time showed that there wasn’t a lack of companies trying to swoop in on the opportunity to work with local mom-and-pops. Ultimately, a good chunk of them would end up migrating to Facebook; the platform’s ad service was easier and cheaper to run than its competitors, and offered more data than they did, too.

“You could just run anything in it, and it was so cheap it didn’t matter,” said Jeromy Sonne, a longtime digital marketer who has since abandoned the platform to start up his own ad-serving network. Facebook was offering something that was “100% self-serve” and didn’t have the price-floors that other platforms–like, say, Doubleclick–were demanding at the time. And it was far easier to navigate than those competitors to boot.

Then the early aughts happened. In an effort to make its platform more user-friendly in 2014, Facebook started throttling the cheap promotional page posts that brands had become accustomed to, forcing the bulk of them to pay up for ad space in people’s feeds or lose the audience they’d spent nearly a decade cultivating.

When small businesses cried foul, Jonathan Czaja, Facebook’s then-director of small business for North America, bluntly said that the platform was simply “evolving,” and advertisers had no choice but to evolve alongside.

So they did; a month after Czaja’s statement, the company boasted in a blog post about a new record of small businesses operating on the platform: 40 million. At the same time, Zuckerberg noted that the company, though it was pivoting to fewer ads in people’s feeds, would be going even harder on microtargeting–a strategy that even he admitted was “pretty controversial” inside the company. Around the same time, employees reportedly began raising red flags about a then-obscure ad firm named Cambridge Analytica, which improperly harvested data from countless Americans in the run-up to the 2016 election.

“‘Using Facebook ads for small businesses is voluntary in the same way that using email for a job search is voluntary.’ ”

By 2017, the combination of Facebook’s ever-growing tranche of user data and increasing scale had left advertisers more or less stuck. When Facebook admitted to marketers no less than a dozen times that it might have flubbed the figures it provided, advertisers shrugged off the miscalculations every time. “Even with the wrong math–it is really small compared to fraud rates on other platforms,” one ad executive told Business Insider at the time. “In digital advertising, you just learn to live with a certain amount of ambiguity.”

Another executive put it more bluntly: “I wouldn’t say they are foolproof, but they are fairly impervious to almost anything.”

Revelations that the company knowingly lied to advertisers for years about how far their campaigns were reaching didn’t send advertisers packing, and neither did the slowly rising prices that many advertisers were paying. It’s average for ad prices on any platform to fluctuate from month to month, but Facebook’s spikes were unusually high. Between January 2017 and January 2018, for example, one analysis found that the prices advertisers were paying for their Facebook ads were spiking up to 122% over a 12-month period.

Meanwhile, finding support as a smaller brand was becoming an increasingly frustrating exercise in futility, Sonne explained.

“Over time the [prices] go up, support gets stretched thin, scaling issues take hold,” he went on. But what was a struggling startup to do? Venture capital had been steadily flowing into a new generation of digital-first brands for more than a decade, which gave them new monthly goals they needed to hit.

“It became a situation where brands or agencies who had expectations of eternal growth could consistently get it from Facebook,” Sonne said, and that their funders now expected the same. But it also made them dependent on a platform that was either increasingly unreliable or downright unusable, depending on which advertiser you asked. Some small businesses reported having their ads improperly flagged by Facebook’s automated ad review process, while other marketers expressed frustration at how buggy the backend systems were.

Apple did not respond to a request for comment. A spokesperson for Meta, meanwhile, noted that “small-business owners around the world tell us our products helped them create and grow their businesses.”

“It’s why we are consistently committed to developing and providing new programs, tools, training, and personalized advertiser support for them,” the spokesperson went on.

The company doesn’t disclose how many of the ten-million-plus advertisers pouring money into a given Meta property each year qualify as a “small business.” The last time Facebook shared that data itself was in a 2019 earnings call when then-COO Sheryl Sandberg said the top 100 advertisers represented “less than 20%” of the company’s total ad revenue. An analysis from the marketing analytics firm Pathmatics found that percentage closer to 6%, at $4.2 billion dollars in spend altogether. The company raked in nearly $70 billion in ad revenue that year alone.

Apple’s next move

Since upending the online ads ecosystem, third-party analysts have seen a surge of advertiser activity–and ad dollars–heading Apple’s way.

Last year, for example, one of these reports found that Apple’s Search Ads–which appear at the top of your iPhone screen when you’re looking for a new app to buy in the company’s App Store–were the source of roughly 58% of all iPhone app downloads. The year prior, these same ads were only responsible for 17%. And earlier this summer, one Evercore analyst projected that Apple’s App Store ads could net the company $7.1 billion in revenue by 2025.

“I think the revenue piece [of the ad market] is less important to Apple than just breaking up Facebook’s total ownership of distribution on mobile,” Seufert said. He pointed out that, for a long time, Facebook dominated the market for driving app installs with its ads. One report from earlier this year found that about three quarters of folks marketing a mobile app rely on Meta’s adtech tools to do so.

“Ads are a revenue opportunity but more importantly, they’re a discovery mechanic,” Seufert went on. “And suddenly, Facebook was determining which apps got downloaded, not Apple. My sense with all this is that they care about the revenue, but I don’t think that was the primary driver. I think it was about the power.”

As far as power plays go, there’s really no better move than honing in on the small businesses that are already disgruntled with Facebook’s platforms. And as Goldner pointed out, with the ongoing economic crush that came with the pandemic, more advertisers–big and small–are shirking display-based advertising like Meta’s for more search-based advertising, like Apple’s.

“As we’re hitting a potential recession, people are moving more towards bottom of the funnel ads to squeeze the margins,” Goldner said. “Whenever a potential economic downturn exists, companies want to focus on maximizing their sales. They care less about goodwill, and more about just keeping their businesses afloat.”

Apple’s impending small business push could also explain the rumblings that the company plans to add search ads to Apple Maps in the near future. After all, one of the best ways your local hardware store or diner can advertise their wares today is via search ads in Google Maps, which have been there since 2016. As Seufert put it, “How could [Apple] justify not doing it?”