Apple’s Game Porting Toolkit is helpful for developers, former Apple software engineer Nat Brown explains, but it still has a lot of work to do to encourage more games to get made for macOS.

Nat Brown, formerly of a game technology team at Apple and previously of Microsoft and Valve, was deeply involved in producing the Game Porting Toolkit. A suite of tools to help developers bring games over from Windows and other platforms to run on a Mac.

Brown joined Apple in 2019, a time when Apple Silicon didn’t exist, but he felt it was to be coming due to the development of iPhone hardware. “I was like, you know, if they’re not doing this for the Mac, then somebody’s broken,” he tells the MacGameCast podcast.

Employees at Apple had the belief that hardware was “holding us back in gaming,” Brown explains, but in his working at Valve, he saw statistics to believe it wasn’t true. The problem was more “non-optimized content” for Apple’s Intel-based hardware at the time.

While Apple used effectively the same Intel hardware as other Windows-based notebooks, and had engineered the hardware to get the best out of the Intel GPU, the issue in profiting from gaming was software. “The only difference, it’s not the hardware, right? It’s the games and the marketing focus.”

Brown refers to a period when Apple didn’t really market itself as a gaming platform, and that Windows PCs were preferred for gaming. However, within Apple, Brown felt there was a culture of believing there wasn’t enough optimization.

When he told other employees that a Mac version of a game runs horribly compared to a Windows notebook, the response was that the developers probably hadn’t converted it to Metal, which Brown felt was very wrong.

“It’s that you didn’t teach them to not render it full resolution on a retina display. They’re pushing four times as many pixels as this Windows laptop, right? So just tell them to scale it down,” he urged.

However, he would be told back by the colleagues that they wanted games to be rendered at the full display resolution, despite the processing limitations. “There’s no way to optimize something for metal on the same Intel GPU and get higher quality for free.”

Brown adds that the vibe within Apple was “very encouraging and I could see this trajectory,” but he also saw the confusion of hardware being the only perceived issue. There was also a “real fixation on native games,” which is a chicken-and-egg problem for publishers and developers.

Namely they had to make money on Mac to be encouraged to produce for it, but since no-one would produce Mac games, there wouldn’t be money available.

Discussing hardware abstraction layers, Brown discusses the use of the Game Porting Toolkit, and how the layers can cause problems for developers in porting titles. Part of the problem is that the portability layer has to deal with features that are added in to the game from the various abstraction layers.

For example, Unreal Engine and Unity are a different layer above systems like the GPU layer, which are above the layer of coding that works with the CPU. However, each of these layers can add in other things, like plugins and custom shaders, which need to be interpreted by the portability layer, the Game Porting Toolkit.

These extras, which land in the graphics stack, need to have the shading language and architectures involved understood for the porting layer to run efficiently.

In one example, games are found to run under the Game Porting Toolkit quite slowly. Sometimes, it has been found that a “bunch of final passes that they perform over the whole screen to do ambient occlusion or bouquet effects” can impact performance.

On a desktop computer with a big power-hungry GPU, this is “no big deal.” On a tile-based deferred architecture like Apple Silicon, “this is not a good way to architect.”

While Apple’s efforts with the Game Porting Toolkit, there are still many things that are difficult to deal with, which includes all of these abstraction layers.

It’s a problem that needs to be managed, but it’s also a problem that needs a bigger workforce. “The game industry does not have access to a deep pool of graphics programmers who understand metal,” Brown adds, in that developers don’t necessarily have the available staff to maintain macOS games, unlike the deeper pools for Windows architectures.

Later in the podcast, Brown raises the GPTK again, and how he worked on things like video guides for developers on how to port their games to Mac. However, he admits there are many missing features that could be beneficial to to developers.

“There’s nothing in the game porting toolkit that helps you take your Visual Studio solution and bring it to Xcode or keep it in sync with Xcode. There’s nothing that helps you integrate building for the Mac into your continuous integration system.”

For major publishers that have many elements that get updated when developers check in code, allowing for compilation to multiple platforms complete with automated testing, the GPTK doesn’t help that sort of situation at all.

Creating tools could help make GPTK a better tool for developers to bring gaming to Mac, but none of these issues are “really attractive” to Apple. “None of those things that truly bridge the tooling problems or truly bridge the demand problems are there.”

Apple’s gaming push

When it comes to actually attracting publishers and developers to Mac, Brown sees Apple as having an upward struggle, and part of that is messaging.

Likening Apple to how big gaming companies can operate, Brown offers that a big player will say to the market that they will “bake in some new gaming features or maybe SKUs, I’m gonna build those. And I need, you know, 25 launch titles. And for this one thing, maybe I’m gonna pay a little bit of money, or maybe I’m gonna do a huge amount of marketing.”

“I’m gonna make this a huge gaming platform, and that’s why you’re gonna invest.” Brown says the hypothetical company would say. However, “That’s not a message that Apple’s currently sending to anybody.”

Instead, Apple is saying “There’s a huge addressable market. You should target it. And people do.”

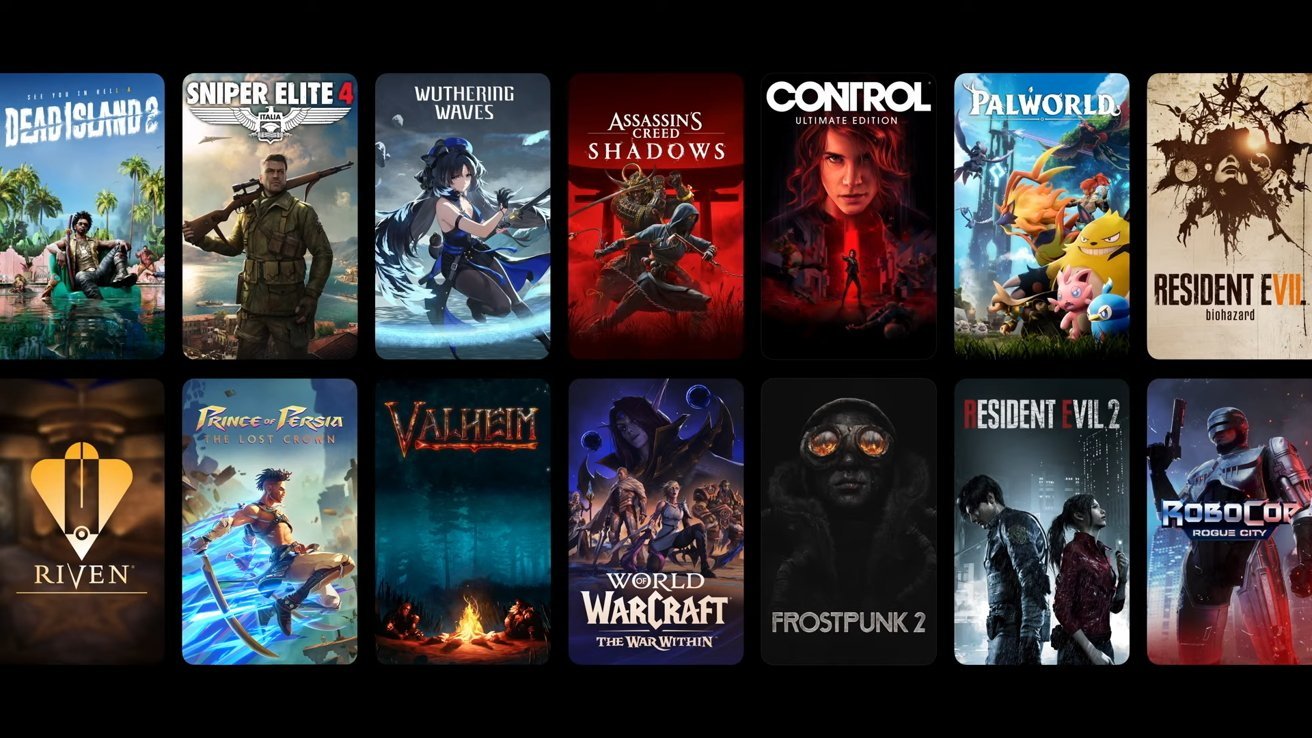

While Apple has convinced companies like CD Project Red, Capcom, and others, Brown hoped that they would get a commercial success so that, when they go to Dice or GDC in the future, they can declare they made a “bunch of money on the Mac.”

“Unfortunately, they haven’t,” admits Brown, based on talking to game industry friends. “None of them had really.”

One possible exception is Kojima Productions, as it benefited from the momentum of the Death Stranding 2 announcement two days after releasing the iOS build for the original game.

Apple could continue the messaging of it operating as a gaming platform and having partnerships for some time, and eventually see success, Brown offers.

“Hey, we’re going to have beats for the next five years, where every four months, here’s another set of games, we’re going to do co-marketing with you, we’re going to put you on TV,” he proposes Apple could tell the games industry.

“You know, we may not pay you, but we’re definitely going to make customer demand here,” Brown added. “We’re going to be telling customers that this is the best place for gaming, and we’re going to showcase your games.”

This would have to work against Apple’s tendency to just showcase Apple in its commercials, he adds.

For example, referring back to an iPhone 16 commercial in the fall, he asks “What was the game that was being played? Do you even, you know? It was Honkai Star Rail.”

“Unless you knew, you wouldn’t know. It was a dude flying through the air, whatever this last one was. He was flying through a subway and punching through walls.”

Brown believes “Apple markets Apple,” not apps and games. By contrast, while major commercials for game consoles do include some shots of the consoles themselves, the main focus is on the games.

“Apple doesn’t seem to know how to do that,” Brown said. “It wants to only showcase itself.”