These days Apple is associated with the iPod, iPhone, iPad, MacBook – game-changing products so wildly successful that they have changed the way we live. But even the most valuable company in the world has had its fair share of marketing missteps and hardware blunders.

Apple wasn’t always as profitable as it is today, and the failure of some of its earlier products would have doomed most other tech companies to the annals of history. Here we take a look back at some of Apple’s most infamous hardware flops. See if you agree, and let us know in the comments of any other questionable Apple devices that you think deserve to be named and shamed.

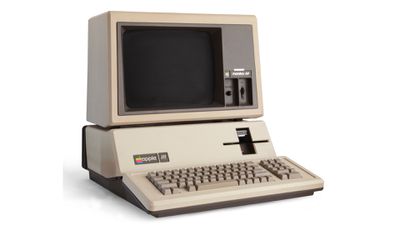

Apple III

The Apple III was the result of a project initiated in 1978 after Apple became concerned that the popularity of its Apple II, launched in 1977, would eventually wane. Originally built with hobbyists in mind, the Apple II was surprisingly popular with small businesses, but Apple was aware that IBM was working on a personal computer specifically aimed at business users, which only made Apple more eager to consolidate its hold on the market. The Apple III therefore had to be the complete system – all things to all users – and a cost-effective addition to any office or home.

A committee of engineers was assigned to the Apple III project, making it the first Apple computer not designed by Steve Wozniak. As it turned out, everyone had their own ideas about what features the Apple III should have, and all of them were included. The project was supposed to be finished in 10 months, but ended up taking two years as a result.

In November 1980 the Apple III finally launched, starting at an eye-watering $3,495, and offering twice the performance as the Apple II and twice as much memory (128KB of RAM). It was the first Apple computer to have a built-in floppy drive, and ran a new operating system called Apple SOS, featuring an advanced memory management system and a hierarchical file system.

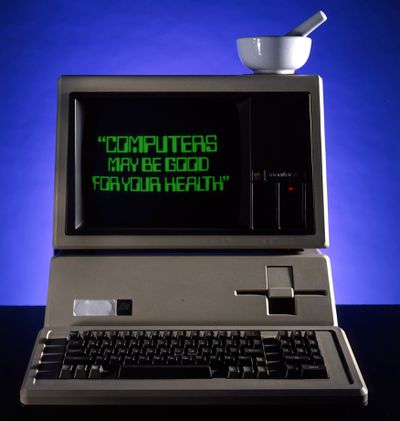

An ad for access to health information via the Apple III

Unfortunately, none of these innovations could save the Apple III from its flawed chassis design, and Apple was forced to recall the first 14,000 machines produced due to serious overheating issues, caused in part by Steve Jobs’ insistence on not including a fan in the case. The problem was so bad that thermal expansion would often cause the chips to pop out of place. Apple even told customers to lift their machine several inches above their desks and then drop it to reseat them. A revised model under the name Apple III Plus was eventually released in 1983 that addressed the widespread failures, but the damage to the computer’s reputation had already been done.

The Apple III was discontinued in April 1984, while its successor was dropped from Apple’s product line in September 1985. The company sold an estimated 65,000–75,000 Apple III computers, with the Apple III Plus taking the total up to around 120,000. Jobs later said that the company lost “infinite, incalculable amounts” of money on the Apple III, and its poor reception caused thousands of US businesses to buy IBM PCs instead.

Apple Lisa

Released in 1983, Lisa officially stood for “Local Integrated Software Architecture,” but was actually a backronym invented later to fit the name of Steve Jobs’ daughter, Lisa. Apple positioned it as a business computer and an alternative to the Apple II. While previous computers relied on text-based interfaces and keyboard input, Lisa was the first personal computer to feature a graphical UI and mouse, interface innovations both first seen in action by Jobs during a visit to Xerox Parc’s research lab in Silicon Valley.

Despite this, starting at just shy of ten grand (around $29,905 by today’s standards), the Lisa was prohibitively expensive for all but the wealthiest of households, and the computer was a flop. By 1986, Apple had only managed to sell around 100,000 units, and the entire Lisa platform was discontinued. Apple was even forced to dispose of some 2,700 Lisas in a landfill in Utah. Fewer than 100 Lisa computers are believed to exist today.

Apple Lisa commercial starring Kevin Costner

Looking back, Jobs felt that Apple had lost its way. “First of all, it was too expensive — about ten grand,” he said in an interview with Playboy in 1985. “We had gotten Fortune 500-itis, trying to sell to those huge corporations, when our roots were selling to people.” Jobs actually got kicked off the Lisa project in September 1980 because of his volatile temperament, but as fate would have it, he subsequently joined the team that ended up developing the first Macintosh.

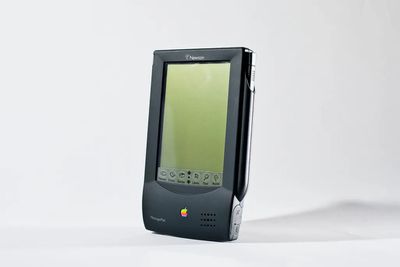

Apple Newton

In May 1992, Apple CEO John Sculley unveiled the Newton MessagePad to a rapt CES audience. He called the sleek black handheld gadget, which was about the size of a VHS cassette, a Personal Digital Assistant (PDA). The Newton PDA, he said, was a completely new category of device. It came with a stylus and could be used to take notes, store contacts, and manage calendars – standard functions of any modern-day smartphone, but revolutionary in 1993. Users could take it out, send a fax, and return it to their pocket, without ever going near a desktop computer.

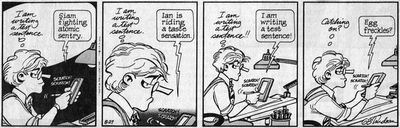

The truly killer feature, however, was its handwriting recognition. Or at least, that was Apple’s original plan. What the audience didn’t know was that it barely worked. Apple shipped the first Newton MessagePad 14 months later for $900, but by that time other companies had already rushed rival PDAs to market, and the Newton still had big problems translating handwritten notes into text. After the negative reviews, it was widely derided in the media – the comic strip Doonesbury dedicated a whole week to lampooning its handwriting recognition issues, and the device even became the butt of a joke in The Simpsons.

Doonesbury comic strip lampooning the Newton (Image credit: Universal Press Syndicate)

Apple battled to make successive versions of the Newton a success, and with the release of Newton OS 2.0 in March 1996 the handwriting recognition had been substantially improved. But it was too little, too late. The brand just couldn’t shake its abysmal debut performance. Worse, Steve Jobs hated it, for two reasons: It came with a stylus (“God gave us ten styluses,” Jobs would say, “Let’s not invent another.”) and it had been Sculley’s pet project. Upon his return to Apple in 1997, Jobs pushed for the product line be killed off. It was discontinued a year later.

“Lisa On Ice”: Episode of The Simpsons making fun of Apple’s Newton

Newton went through eight versions of the hardware, with Apple spending $100 million on its development. Only an estimated 200,000 were ever sold. But it wasn’t all a waste. The same thinking behind the PDA would eventually bring us the iPhone.

Macintosh TV

In an age where watching streaming video on your phone or PC doesn’t even raise an eyebrow, Apple’s original computer-television hybrid now seems like a solution in search of a problem. But when it launched in 1993, the idea of watching TV on your Mac was completely ahead of its time.

The black chassis of the Macintosh TV was essentially an LC 520 fused with a 14-inch Sony Trinitron CRT. It came with a CD-ROM drive and remote control, while a built-in tuner card with connecting coax cable allowed broadcasts to be displayed in 16-bit color. Unfortunately, users had to choose to either watch TV or use their Mac. It couldn’t display TV in a window (Picture in Picture hadn’t been invented yet) and it was impossible to capture video, although users could save still frames of broadcasts as PICT files.

On the face of it, the Macintosh TV offered faster performance than the standalone LC 520, thanks to a 32MHz Motorola 68030 processor. In reality though it was bottlenecked by a 16MHz bus. Also, the 5MB of RAM was only upgradeable to 8MB, whereas the LC 520 could max out at 36MB. Costing $2,099 at launch, Apple’s TV-Mac mashup was not cheap, and it failed to catch on. It was discontinued in 1995, two years after its release, by which time Apple had shipped just 10,000 units.

Pippin

Launched in 1996 with the help of Japanese game company Bandai, the Pippin was Apple’s infamous stab at a CD-ROM based game console, but it was badly marketed, poorly supported, and vastly overpriced. The Pippin arrived at the height of the console wars, a time when home computers had yet to become commonplace. Apple’s ill-fated plan was to shift the market dynamic with a hybrid computing/gaming device.

On the face of it, the Pippin was just that, boasting some unique features that all other console rivals lacked. Based on Macintosh architecture from the early-to-mid ’90s, the Pippin ran a simplified version of Mac OS 7, making it faster than other consoles. It was also equipped with a veritable selection of ports, supporting not only modem and printer connections, but also offering users the ability to connect external peripherals like keyboards and mice.

Unfortunately, Apple’s intention to give Pippin users a computer-like experience in a console form factor was partly the reason for its downfall. Costing $650, the Pippin was around $400 more expensive than leading rivals such as the PlayStation and Nintendo 64. And despite Pippin’s fast performance, competing consoles had the edge in terms of software, with many sporting extensive games catalogs, whereas only 25 titles were released for Pippin owing to poor third-party developer support on the part of Bandai, a relatively unknown name among the gaming community.

Apple didn’t plan to release Pippin on its own, intending to make the platform an open standard by licensing the technology to third parties, similar to its licensed Mac clone program in the late ’90s. However, when Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, he canned the company’s clone efforts and subsequently shut down Pippin development, leading Bandai to halt the production of all models of Pippin by mid-1997. Apple had hoped to ship half a million consoles a year, but only sold a total of around 42,000 in the device’s short lifespan.

20th Anniversary Macintosh

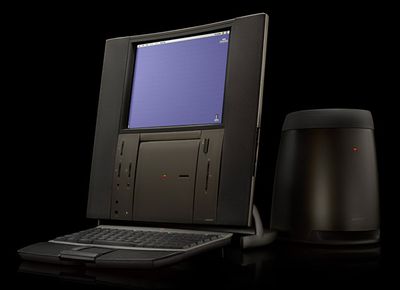

Released in March 1997 to mark Apple’s 20th year in business rather than the anniversary of the Mac, the “20th Anniversary Macintosh,” or TAM as it became known, might look odd by today’s standards, but it was a unique machine in its own right.

Its strikingly thin and upright “all-in-one” design housed several novel features, including a built-in 12.1-inch LCD flat-screen display, vertically mounted CD-ROM and floppy drives, and an integrated TV/FM tuner. The TAM ran a modified version of Mac OS 7.6.1 to control these features, while a 250MHz PowerPC 603e CPU and 64MB of RAM ensured performance was nothing to sniff at. It even had a custom Bose sound system with two accompanying speakers and a subwoofer built into the external power supply.

TV commercial for 20th Anniversary Macintosh

Delivered to customers via a direct-to-door service undertaken by tuxedoed concierges, the TAM was marketed as an executive machine, but at $7,500, the executive pricing proved too much of a turn-off, and sales were poor. In the final weeks of its availability, Apple slashed the price of the TAM to $2,000, but this only served to anger people who had paid full price, and Apple was forced to reimburse early adopters with a new PowerBook.

Only 12,000 TAMs were made, many of which were never sold. The system lasted barely 12 months in Apple’s product lineup and was discontinued a year later in March 1998, shortly before the launch of the iMac G3, which offered similar specs but a larger screen, and all for just $1,299.

Power Mac G4 Cube

Unveiled on July 19, 2000, the Power Mac G4 Cube was an engineering marvel and a statement piece of Apple industrial design. At less than one fourth the size of most PCs available at the time, the fanless machine represented an entirely new class of computer, featuring a powerful G4 PowerPC processor, discrete Nvidia video card, AirPort card for Wi-Fi, and a DVD burner, all packed neatly into an elegant eight-inch cube suspended inside a transparent molded acrylic case. Steve Jobs called it “simply the coolest computer ever,” and going on first impressions, it was hard to disagree.

But the Cube was doomed almost from the start. Upgradability was limited – a handle in the bottom of the Cube allowed users to pull the innards out of the case, providing access to three RAM slots and space to insert an AirPort card, but there were no PCI slots and the proprietary video card was shrunken down to fit into the tightly enclosed space. It was also too expensive, even by Apple’s standards. The lowest-priced model cost $1,799, which was $200 more than the far more upgradeable Power Mac G4.

Apple promotional video for Power Mac G4 Cube

Apple sold fewer than 150,000 units in 349 days, and on July 3, 2001, Apple announced it was suspending production of the Cube indefinitely. “Cube owners love their Cubes,” said Phil Schiller, Apple’s then vice president of product marketing. “But most customers decided to buy our powerful Power Mac G4 minitowers instead.” Apple CEO Tim Cook would later describe the G4 Cube as “a spectacular failure.”