My older kid was trying to apply for college at a university in Florida. Perversely, its website refused to appear. He tried Safari, Firefox, and Chrome on his Mac and Safari on his iPhone. Only his devices appeared to be affected. Switching to cellular worked, isolating the problem to our local network. Yet my Mac laptop could reach the site just fine. Reviewing our routers and other settings, I couldn’t find a reason for this failure.

What I finally discovered? Our primary network and Wi-Fi router had outdated DNS server information. Our provider, CenturyLink, had at some point updated the servers it uses to provide domain name system (DNS) record lookups. When you type in something like podunk.edu, your operating system has to perform a DNS query to convert that address into a machine number (an IP (Internet Protocol) address) that it uses to create the actual end-to-end connection between a browser or other software and a server.

DNS servers are unloved bits of utility. In the late 2000s, many ISPs had overlooked the speed of these servers, which may perform billions of simple queries a day or more for a network of users. A slow DNS lookup could make everything on your devices sluggish as you browse around. (The information is cached for minutes to days, so the first lookup is the painful one.)

Some third parties grew on the back of providing high-quality freemium DNS lookups: super-fast responses for free, and you could pay extra for filtering and other services. Eventually, Google got into the business with Public DNS, a free service uncoupled from ISPs. Others followed.

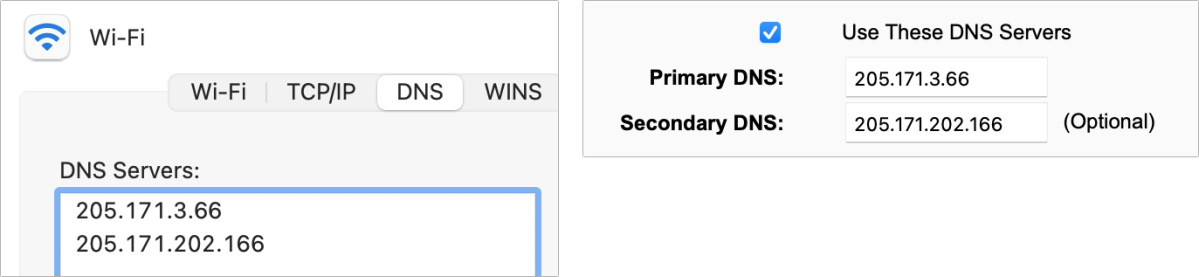

On most home networks, your ISP provides you details to enter manually into your router setup to bootstrap access. This almost always includes the IP addresses of two DNS servers–primary and secondary–which you have to enter in numeric form. It’s a chicken-and-egg problem: you can’t use DNS to look up a name if your network or devices don’t know how to find a DNS server. You may never have to change those details. Some people in the last decade-plus have changed those settings to point to Google other free or paid DNS services.

When you connect a Mac, iPhone, or other internet-capable hardware to a local network via Wi-Fi or ethernet, nearly all home networks automatically assign it a local network address. That assignment points your device’s DNS requests to the router, which in turn relays them to the DNS servers it has configured in its settings.

In my case, CenturyLink is our provider, and I likely hadn’t changed our DNS server numbers for as long as I can remember. But on my Mac laptop, I have messed with them at times just for that computer, for testing and for speed. (Go to System Preferences > Network, select Wi-Fi, click Advanced, click DNS, and click the + at the bottom-left corner to add one or more custom entries.) These custom entries override the DNS server info at the router level in favor of the ones you picked.

At this point, I had a hunch. Had CenturyLink changed its DNS server addresses without, say, notifying its customers? Sure enough, CenturyLink’s help page on DNS server addresses showed ones I hadn’t seen before and weren’t set up on my router. I updated my router settings, applied them, and suddenly the “broken” university page loaded fine on all our networked devices.

The only mystery remaining is how CenturyLink is running a semi-broken DNS old server that seemed to omit only one site on the internet.

This Mac 911 article is in response to a question submitted by Macworld reader Benjamin.

Ask Mac 911

We’ve compiled a list of the questions we get asked most frequently, along with answers and links to columns: read our super FAQ to see if your question is covered. If not, we’re always looking for new problems to solve! Email yours to mac911@macworld.com, including screen captures as appropriate and whether you want your full name used. Not every question will be answered, we don’t reply to email, and we cannot provide direct troubleshooting advice.