Whenever we have a new generation of processors from AMD and Intel, a lot of things change. Of course, the power balance among the best processors shifts, and there’s a seemingly endless number of comparisons to start making between each lineup. This year, however, AMD and Intel barely moved the needle.

That’s the despite the fact that both companies debuted entirely new architectures, both of which promised to radically change how our PCs work and perform. Those promises just fell flat, particularly at release. We still saw standout releases like the Ryzen 7 9800X3D, but even with so much hardware flying around, there’s been little reason to go out and buy it.

Here’s how we got here.

AMD played with its food

AMD started the CPU battle this year with its Ryzen 9000 CPUs. The setup was simple. AMD planned to leverage its entirely new Zen 5 architecture to build a world-class desktop and mobile lineup. Instead of staggering its releases, as it has done in the past, AMD kept the desktop and mobile launches close together, flooding the market with Zen 5 options over the course of just a few weeks.

The company described Zen 5 as a “new foundation” for Ryzen moving forward. It talked about big efficiency improvements with chips like the Ryzen 9 9950X and world-class gaming performance with the eight-core Ryzen 7 9700X. That’s not to mention new architectural features like a 512-bit data path for AVX-512 instructions, which is a big boost to AI workloads and other tasks like PS3 emulation.

But then the CPUs showed up. AMD provided good gen-on-gen improvements in productivity apps, but it was largely still competitive with Intel’s 14th-gen offerings. The flagship Ryzen 9 9950X, performant as it was, couldn’t manage to beat the Core i9-14900K across apps. It took AMD two years to release a new flagship, and the result was a rather familiar CPU with performance that, in most apps, was just middling.

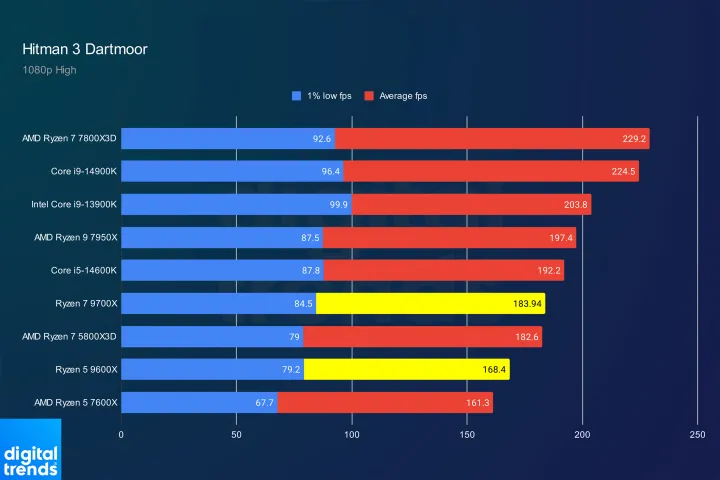

PC gamers really got the short end of the stick, though. In the vast majority of games, the new crop of Ryzen 9000 CPUs performed identically to their less expensive Ryzen 7000 counterparts. Worse, the last-gen Ryzen 7 7800X3D still topped benchmarks, giving PC gamers little reason to invest in AMD’s “new foundation.” It’s little surprise that AMD’s Zen 5 CPUs saw very little interest from buyers when they released.

AMD eventually revisited the performance on Ryzen 9000 CPUs, offering up to a 17% boost in performance through various updates. The company addressed latency issues on the 12-core and 16-core models, and it introduced a higher-power mode for the six-core and eight-core models. Combined with some key Windows updates, AMD’s Ryzen 9000 lineup ended up in a much better spot.

But the damage had already been done. Even with better performance, AMD’s Ryzen 9000 lineup just didn’t deliver the performance boost AMD had promised, particularly in games. They became an even more tough sell with chips like the Ryzen 7 7800X3D floating around, which offers performance that’s hard for AMD itself to contend with.

Intel’s struggles never let up

AMD struck first this year, but Intel fell into very similar trappings to Team Red. For Intel, it focused on a radically new architecture for its Lunar Lake laptop CPUs. That new architecture made a lot of strides in laptops, particularly in machines like the Asus Zenbook S 14. But Intel decided to take its architecture focused on efficiency and battery life and apply it to high-performance desktop CPUs with its 15th-gen Arrow Lake offerings.

That was a mistake, which becomes abundantly clear if you read my Core Ultra 5 245K review. With this architecture, Intel decided to push its efficient (E) cores to the forefront of performance, and reserve its performance (P) cores for workloads that could use an extra boost. This design is very similar to Qualcomm’s approach to chip design, and it does wonders for battery life in laptops.

It just kind of stinks for high-performance desktops.

With a desktop, you don’t have to worry about battery life. And more importantly, there’s far less concern for thermals, with flagship CPUs often getting the liquid-cooling treatment for maximum performance. Intel’s highly efficient mobile architecture fell flat on its face in desktops. In the best situations, Arrow Lake CPUs offered middling performance gains. And in the worst situations, they were flat-out worse than older, less expensive options.

The flagship Core Ultra 9 285K wasn’t a complete disaster, but it definitely wasn’t a strong release. Intel could rarely match the Ryzen 9 9950X from AMD, which as I covered in the last section, was a disappointing CPU in its own right. Gaming was much worse, though. Not only did Intel not provide a significant improvement in gaming performance; in most games, Intel’s 13th-gen and 14th-gen offerings were straight-up faster.

Just like AMD, Intel has put out some updates that supposedly improve performance for Arrow Lake processors. I haven’t tested those updates yet, but similar to the situation AMD found itself in with Zen 5, it’s hard to crawl back from a devastating launch.

To add fuel to the fire, Intel faced massive instability issues on 14th-gen and 13th-gen CPUs throughout the year, which could completely brick hardware if unaddressed. A complete lack of communication during the months-long problem only led to more speculation on the issues, and certainly didn’t inspire confidence for an entirely new generation of underperforming Intel chips.

A new perspective

There are a lot of parallels between AMD and Intel this year, but the most important is this: AMD and Intel designed their new architectures for laptops. That’s speculation on my part, but it’s really hard to imagine these architectures were angled toward desktops with their middling performance. And it’s even more difficult to imagine when you consider how impressive Lunar Lake and Zen 5 are in laptops.

Concurrent to the new ranges from AMD and Intel, Microsoft and Qualcomm launched the Copilot+ initiative — a range of laptops focused on AI features, all-day battery life, and performance that could dethrone the MacBook Pro. AMD and Intel, whose chips had been the driving force behind the loud fan noise, poor battery life, and high heat that Windows laptops came to be known for, needed an answer to new efficient chips like the Snapdragon X Elite.

Intel and AMD don’t just spin up new architectures out of the blue. It’s a years-long process, but clearly the companies knew a major shift in Windows laptops was coming. And Zen 5 and Lunar Lake seem specifically designed to take advantage of that shift.

By doubling-down on architectures for desktop and mobile, the consequences of focus show up pretty clearly here. There isn’t a massive boost on desktop, and sometimes no boost at all. If you were waiting for an upgrade, Zen 5 and Arrow Lake only served to showcase that last-gen options were the best bet for PC gamers.

It’s no secret that your CPU isn’t the main component driving gaming performance. Your GPU is. However, we still see a steady uplift in gaming performance generation over generation, and that uplift was completely absent this generation. Here’s to hoping the next generation doesn’t continue that trend.