Let me tell you a quick story. I like Johnston & Murphy shoes. I’ve been trying to get this pair for weeks, but since it seems a lot of other people like it too, it’s been out of stock in my very common shoe size. So I did a Google search to see if I could find other stores that had it in stock.

And wouldn’t you know it, there was another Johnston & Murphy site, almost the same one with “USA” added to the URL. It looks similar to the other site, but it had every single size of that shoe in stock, ready to buy. And it was half off the original price, what a deal! It must be an overstock outlet for the brand. So I put the shoe in my cart, and prepared to check out.

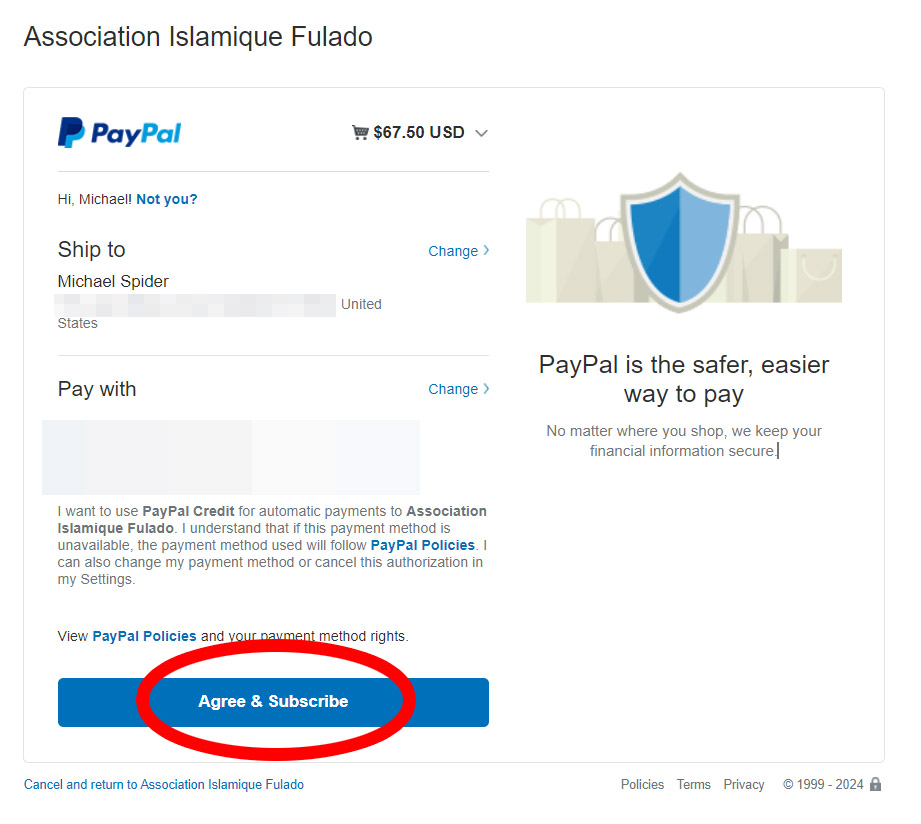

But for some reason, PayPal was the only payment option. No big deal, I often use PayPal and it has a purchase security program. So I went through the PayPal interface…and the very last step in the process, the one that would confirm the order, said “Agree and Subscribe” instead of “Purchase.” It also asked me to pay someone who isn’t Johnston & Murphy, but “Association Islamique Fulado.” That name didn’t return any useful Google results — Its address is somewhere in Luxembourg, assuming it’s the same person or organization.

Not pictured: a shoe sale.

Michael Crider/Foundry

I’ve seen that button before. It’s used when you want to make a recurring payment to a charity or a creator, a la Patreon. Why would I need to “subscribe” for a one-time payment option?

To be honest my red flags were raised from the start when I saw the URL, but at that point I went into Arkham Asylum detective mode. Step one was to check out that fishy URL with a Whois lookup. The main Johnston & Murphy domain has been registered for almost thirty years, and though it’s gone through a private registrar, that registrar is based in Florida in the US. If a judge in the US were to issue a subpoena to Johnston & Murphy, they’d have someone to track down.

I tried the same lookup with the “USA” alternative site, the one that had the shoe in stock and was ready to sell it to me via a PayPal subscription. This one was registered in January of this year, to a Chinese company, with a Gmail address for the private registrar.

Now, since I’m posting this story publicly, I’m not going to flat-out accuse this site of being a scam. But I can’t think of any legitimate reason that a Johnston & Murphy domain for an American company would be using a registrar in China. And I can’t imagine why the PayPal system would only let me “subscribe” to pay for it, especially when the verified site only lets you pay with a credit card. I decided to wait for those shoes.

I will say that fake retail storefronts are incredibly common, even showing up highly in Google searches like the one that I did. I’ve seen a lot of similar — and similarly suspicious — sites selling hugely discounted kayaks in Google shopping results. They were likewise new stores, with designs that aped or just outright stole the layout of other stores, and with prices and availability that seemed too good to be true.

A recent report from German firm Security Research Labs (spotted by BleepingComputer) found a ring of fake retail sites operating tens of thousands of domains. The “BogusBazaar” ring took in 850,000 orders, mostly from the United States and Germany with the rest of the “sales” going to Canada and Western Europe. Shops are quickly set up and copied with automated WordPress tools, including e-commerce plugins for accepting info from PayPal, Stripe, and other methods.

What’s the point? They don’t simply charge the money and try to get away with it — which is often harder than it seems, now that banks, credit card companies, and other payment processors are on high alert for fraud. Instead they’re collecting personal information, especially addresses and credit card numbers. Put all that info together, and it’s a valuable start to an attempted identity theft.

SRLabs says that the BogusBazaar system operates with a small team of developers, who then sell their services to other fraudsters in a “franchise” system, mostly out of China. They look for recently-abandoned domain names that have decent search results in order to pull in traffic. It’s a method that’s “low-key” and “highly scalable,” bringing in stable income via information theft. When one ring of stores gets discovered and wiped from the search engines, they’ll just copy and paste with a new set, rinsing and repeating their techniques to gather more data.

Remember, in online shopping as in life: If something seems too good to be true, it probably is.