Over the last few weeks, I’ve spent some time helping my late friend Oliver’s elderly father JP and his wife Gretel, who are preparing for a move to an assisted-living apartment in another state (see “Oliver Habicht Dies of Pancreatic Cancer at 53,” 26 September 2020). They’re internationally renowned scientists in nutritional epidemiology and nutritional anthropology, and while they’re both suffering the seemingly inevitable physical ravages of age, they remain fully mentally competent, if occasionally slowed by medications and fatigue.

I had promised Oliver that I’d stand in for him as necessary, and since he had been JP and Gretel’s primary tech support person for years, I was happy to help when they said they had some computer questions. I knew what I was getting into, more or less, since JP was one of my first consulting clients in 1987 when I was a junior at Cornell and he lived just a block away. I’d go over, decipher the notes he left himself by naming empty folders on his Mac Plus, and help him work through various software and hardware problems.

I had time for only a few visits before they were slated to leave, and their house was being packed up around us, so they had three areas to focus on: dealing with old hardware, rationalizing their backup strategy, and coming up with a better password management system. In each case, I was struck by the fact that Apple has put some effort into addressing these problems recently, but in ways that won’t necessarily help older Mac users who aren’t using the latest hardware, operating systems, and technologies.

I don’t want to make overgeneralizations about people in their 70s, 80s, and 90s, since we have many highly technical and capable TidBITS readers in those age ranges (not to mention our centenarian—see “George Jedenoff: A 101-Year-Old TidBITS Reader,” 17 June 2019 and “102-Year-Old George Jedenoff Publishes His Autobiography,” 26 August 2019). But from what I’ve observed among the mainstream public, it’s increasingly common for the elderly to rely heavily on computers, tablets, and smartphones but have trouble with the constant change in the tech world. It’s not that the systems are necessarily too hard (though some could improve); it’s that there is too much to learn and it changes too frequently. Plus, those who have been using technology for decades tend to have a lot of older hardware around, further complicating upgrade and compatibility questions.

It’s tempting to fall back on that old saw, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” and sometimes that’s true. But in the tech world, staying put often isn’t feasible. Some apps really do break purely from age (like 32-bit apps in macOS 10.15 Catalina), some updates require new minimum hardware and OS requirements, and compelling capabilities appear in new and revised apps. Some level of change is inevitable, but when that change has been delayed for years, everything gets harder. Here’s what I encountered.

Old Hardware

On my first visit, JP and Gretel had a box of random tech bits—keyboards, mice, USB hubs, power supplies—labeled with my name on a sticky note. (Sticky notes were everywhere, in fact, since they’re excellent reminders, and JP has long fit the mold of the absent-minded professor.) They also had an old MacBook Air, Mac mini, iMac, Dell PC tower, and some tiny PC laptop that were weighing on them. None were in use, but they’d been kept instead of recycled in part because it’s hard to decommission an old computer soon after getting a new one. You never know if you might need the old one for something, and regardless of whether the machine has value to anyone, it’s important to erase the internal drive before disposing of it.

It was my job to erase the drives and get rid of the machines. Given the age of these machines, that’s proving more difficult than I anticipated. The 2010 MacBook Air was easy: I booted into macOS Recovery, reformatted the SSD, and reinstalled macOS. We even have a friend who wants to adopt it. But while I was able to erase the iMac’s hard drive, it insisted on having my Apple ID to install 10.11 El Capitan, and the installation continually fails. Although the Mac mini seemingly boots, I haven’t yet been able to get it to drive a display, so I can’t see what’s on the screen or erase its drive. I haven’t gotten to the PCs yet—they may end up being drilled and recycled.

My point here is that if preparing a computer for disposal is this involved for someone with my experience, knowledge, and hardware (and the strength and flexibility to move computers and screens around), it will be beyond many older people. That’s especially true because cleaning off a Mac to dispose of it isn’t something that anyone other than a consultant or IT admin will do frequently.

Happily, this is one of those situations where Apple is moving in the right direction. First, the company encourages users to trade in or recycle old hardware. Second, starting in macOS 12 Monterey, Apple has made it easier to prepare a Mac to be passed on, albeit in a rather hidden fashion.

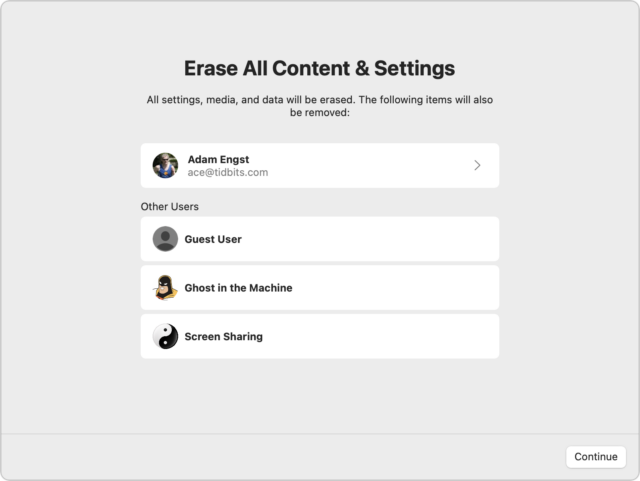

Here’s how you’ll prep a Mac for a new life if it’s running Monterey. Open the System Preferences app, but instead of working inside its window, as you normally do, choose System Preferences > Erase All Content and Settings to start the Erase Assistant. After clicking Continue, it quits all your apps and proceeds with erasing all the data. Or at least I assume so since I didn’t let it erase my boot drive.

Alas, many older users may not have Macs that can run Monterey or may not have seen the utility of upgrading. For Macs running anything earlier than Monterey, hold Command-R at boot to start macOS Recovery, from which you can use Disk Utility to erase the boot volume and then reinstall a clean version of macOS.

Better Backups

As long-time Mac users with advice from Oliver, who was an IT professional, JP and Gretel both had Time Machine drives for local versioned backups and offsite backups to IDrive. They understood the importance of offsite backups but weren’t happy with IDrive and wanted a new Internet backup service. They were also laboring under two common confusions about backups:

- They wanted to know if they could store other files on their capacious Time Machine drive. Technically, that’s possible, but it’s a bad idea to mix backups and original data on the same physical drive, particularly for people who don’t have a crisp awareness of how to maintain multiple backup systems.

- Along with IDrive, they were paying for extra storage on Dropbox and Google Drive and wanted to know if they could back up to that storage. Again, it’s technically possible, but both provide online syncing and storage, not true backup. For backup with versioning and protection against file deletion, a backup app is necessary.

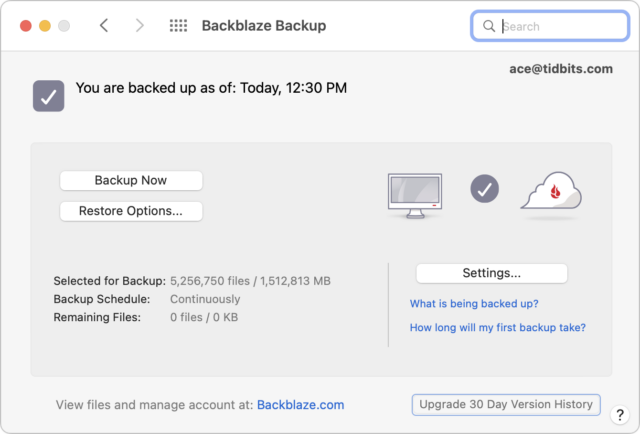

After talking it through, and taking into account that they were leaving the area shortly, I set them up with Backblaze for $70 per computer per year and helped them turn off auto-renewal on the IDrive account. They also dropped their Dropbox accounts to the free level, but stuck with the lowest level Google One storage plan to ensure enough space in Gmail.

Backblaze is a good system, particularly in the set-and-forget category, which is essential for elderly folks who don’t need to spend more time managing their backups. The main problem JP and Gretel have had so far is the disconnect between the preference pane on the Mac and the Web-based interface for additional management and file restoring. They also fell prey to the watched-pot problem of the first backup, which took a few days to complete.

Apple has addressed the need for backups for iOS and iPadOS with iCloud Backup, but I remain surprised that the company hasn’t released an iCloud Time Machine that would back up Macs to paid iCloud+ storage (see “Five Enhancements for Future Apple Operating Systems,” 19 May 2022). Such a built-in system would encourage more Mac users—regardless of age—to protect their data since they wouldn’t need to buy an external drive, and it could serve as an offsite backup for those who already use Time Machine locally.

Shared Passwords

The final area of concern surrounded passwords. I don’t know why, but JP and Gretel had never previously made the jump to a password manager. Part of that may have been JP’s idiosyncratic notetaking habits and Gretel’s excellent memory (when signing up for Backblaze, she was able to rattle off her American Express credit card number, expiration date, and CVC code with no difficulty). Nonetheless, Gretel was aware that she might not remember a one-off password or fact, so she fell back on handwritten reminders on sheets of notebook paper. Similarly, though more digitally, JP maintained a Word document with coded notes that described his passwords for different sites such that only he or someone who knew him well would be able to figure out the passwords. He had recently shared that document with family members but was aware that better solutions existed.

Moving elderly people to a password manager worries me. Password managers are better in every way—they’re faster, easier, more secure, more easily shared, and a boon for multiple device use—but they require learning an entirely new way of logging into websites, which seems to be tough. If a password manager causes more login friction than it saves, it will become more trouble than it’s worth.

Initially, I was thinking it would make more sense to help them come up with a better low-tech solution for backup and set Google Chrome to save passwords for them, but JP was insistent on setting up LastPass and sharing it with members of his family. We did that, and I showed him how LastPass asks to record newly created or updated logins, but I have some trepidation that it will work out in the end. It’s possible that Apple’s Passwords and iCloud Keychain would have worked as well, but Apple’s solution lacks the sharing features of LastPass and 1Password that make them compelling to families who might need to access the accounts of relatives who become incapacitated or pass away.

The ultimate solution is of course passkeys, which are both easier and more secure than passwords, but I fear that older folks will have trouble adjusting to yet another new authentication system. (More on passkeys soon.) If JP and Gretel are at all representative of their generation, the biometric aspects of passkeys may not be as much of a win for older people as well—Touch ID fails for both of them, and I’ve seen suggestions that fingerprint scanning accuracy decreases with age due to skin becoming smoother and less elastic. Face ID shouldn’t suffer such issues, but plenty of Apple devices continue to rely on Touch ID.

So, again, it looks like Apple is moving in the right direction with password management, passkeys, and Legacy Contacts, but it may be too late for those who lack compatible hardware or for whom an entirely new way of authenticating may be challenging.

![iOS Decoded: iOS 18.3 RC new hidden features, changes and updates [Videos]](https://techtelegraph.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/iOS-18.3-Release-Candidate-218x150.jpg)