Near the end of his testimony on April 8, Philbrick “made one more startling disclosure,” reported Time magazine: “One of the teachers at the secret schools for revolutionists was none other than Dirk Struik, professor of mathematics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, longtime sponsor of many organizations listed as subversive.”

Struik had avoided political activity when he first arrived in the US but proudly participated in what he later called “the struggle for what I saw as social justice” after he was naturalized in 1935. He had indeed helped fund Boston’s Samuel Adams School for Social Studies, a Communist school modeled after the Jefferson School of Social Science in New York City; he also wrote for the Marxist publication Science and Society and was active on the National Council of American-Soviet Friendship. At one meeting in Cambridge in 1947 that Philbrick attended, Struik had presented a review of Lenin’s State and Revolution.

Struik told journalists that he was a “Marxist in the broadest sense,” but he denied being a member of the Communist Party. In fact, as required by state law, he had taken an oath pledging to support both the US and Massachusetts constitutions.

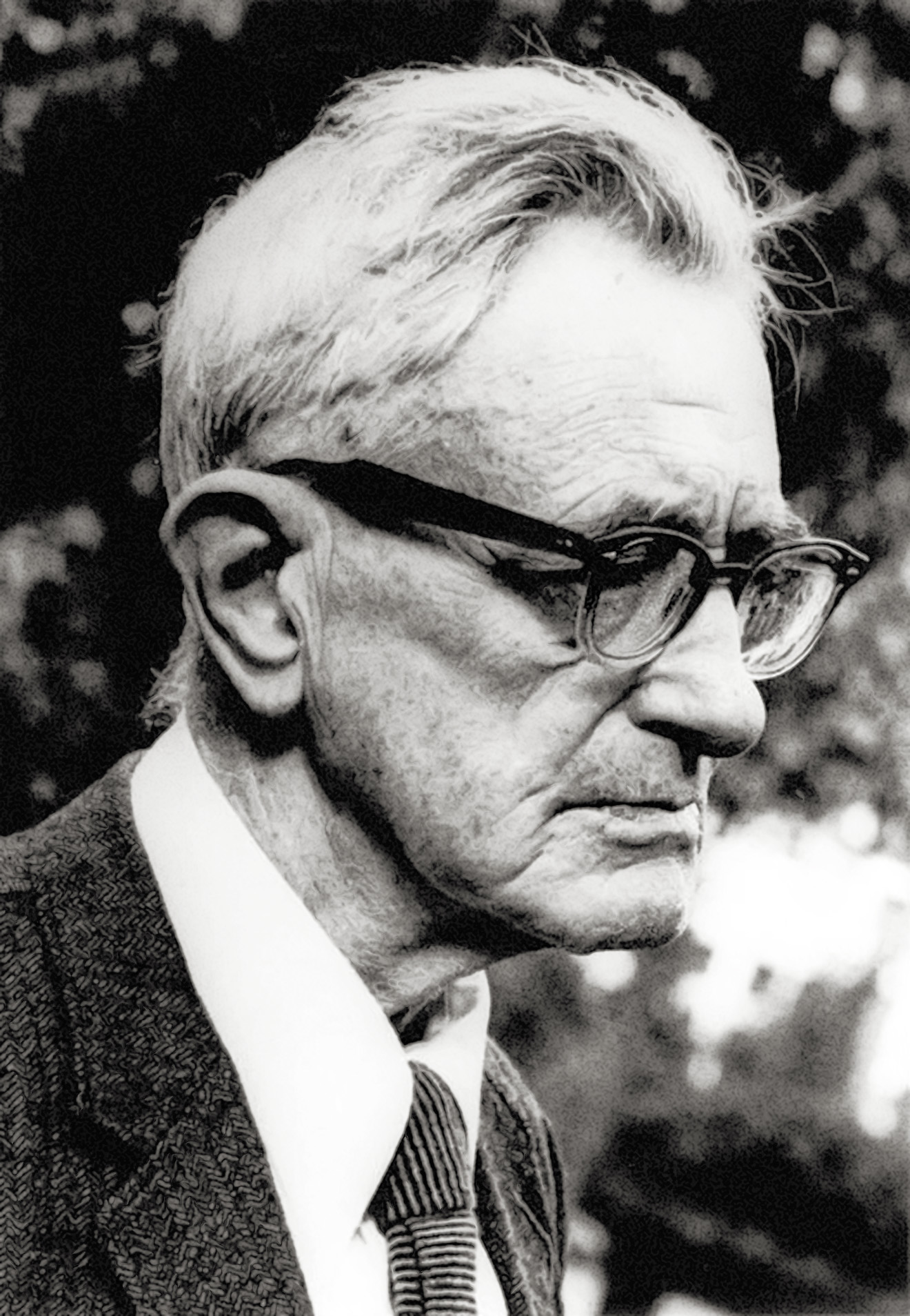

MIT MUSEUM

In a meeting with MIT president James R. Killian, Struik said that he taught only mathematics at MIT, never political ideology. Killian agreed, saying that on several occasions the Institute had placed “observers” in Struik’s classroom and none had reported hearing anything improper.

In May 1949 Killian issued a three-page statement reading in part, “The Institute believes that Professor Struik, who denies that he has committed any crime, should be considered innocent of any criminal action unless he is proved guilty.”

On July 24, 1951, Struik was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). He briefly attempted to explain that he was a Marxist but not a Communist and then refused to answer most of the committee’s questions, including whether he was or had ever been a member of the Communist Party, citing his Fifth Amendment right not to incriminate himself. The story was front page news in the Boston Globe.

On September 12, 1951, a Middlesex County grand jury indicted Struik for “conspiracy to overthrow the governments of the United States and Massachusetts, and for advocating the overthrow by violence of the government of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts,” the Globe reported. He was released on $10,000 bail.

The MIT faculty held a hasty and sparsely attended meeting that afternoon—the fall term hadn’t started—and voted to suspend Struik with full pay until the case was resolved. But beyond Philbrick’s testimony, at that point there was no evidence that Struik was anything beyond a mathematician with a fondness for Marxism and social justice—hardly grounds for firing. Karl Taylor Compton, Class of 1908, SM 1909, PhD 1912, chairman of the MIT Corporation and a former MIT president, defended keeping him on the payroll, noting: “As an institution we did not feel justified in taking action on the basis of rumors and charges that no one could substantiate.” And Rosalind Williams, professor emeritus in the Program on Science, Technology, and Society, recalls that her grandfather, chemical engineering professor Warren K. Lewis, told her MIT believed that only the Institute should decide if he was worthy of a faculty appointment.