Key Takeaways

- Nyquist Theorem is audio’s foundation, dictating digital sampling rates for optimal quality.

- Lossy compression sacrifices audio detail for file size, stripping harmonic richness & reverberation.

- Poor compression leads to noticeable audio distortions like clipping, metallic sounds, and loss of dynamics.

You may have heard that your music is “compressed” and that if it were less compressed, or even uncompressed, it would sound much better. However, if you know what compression is and how it works, you might not be in such a hurry to “expand” your musical horizons.

Meet Mr. Nyquist

Before we get into it, it’s important to talk about the Whittaker–Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem since it’s based on the work of Harry Nyquist, Claude Shannon, and (all the way back in 1915) E.T. Whitaker. Nyquist is, however, the best-known proponent of the theorem, so you’ll often just see it referred to as the Nyquist Theorem.

Credit aside, the Nyquist theorem is the foundation of digital audio. It states that to digitally represent a sound, you must sample it at least twice the highest frequency in the sound. For example, CDs sample audio at 44.1 kHz, capturing frequencies up to 22.05 kHz—just beyond the upper range of human hearing.

Sampling can be seen as the base form of digital audio compression. After all, you can increase the sample rate and technically have a more accurate recording of the original analog sound, but your file sizes will grow exponentially. Increasing your accuracy beyond what human ears can perceive isn’t worth the storage space required, and so you have a basis for how much space an audio recording should use at most.

Of course, these days higher quality audio offers push beyond CD quality with rates like 48KHz, but the point of diminishing returns is relatively clear.

Lossy Compression Cuts the Audio Fat

Audio compression comes in two flavors: lossy and lossless. Lossless compression (like FLAC) retains every bit of the original data but results in larger files about half as big as a CD audio recording.

Lossy compression (like MP3 or AAC) discards “unnecessary” data to save space, based on psychoacoustic models of human hearing. These models assume we won’t notice certain sounds masked by louder ones, or frequencies at the fringes of the typical human hearing range.

This approach isn’t perfect, however. While lossy compression removes redundant audio data, it can also strip away subtle details, such as the reverberation of a room or the harmonic richness of instruments. This results in what some audiophiles might describe as a “flat” or “lifeless” sound, especially at low bitrates like 128 kbps.

Sample Rate and Bit Depth Matter Most

Compression isn’t the only factor that affects quality; the original sample rate and bit depth are just as critical.

As I mentioned above, the sample rate is how often the sound is measured per second. Higher sample rates (e.g., 96 kHz) capture more detail but require more storage.

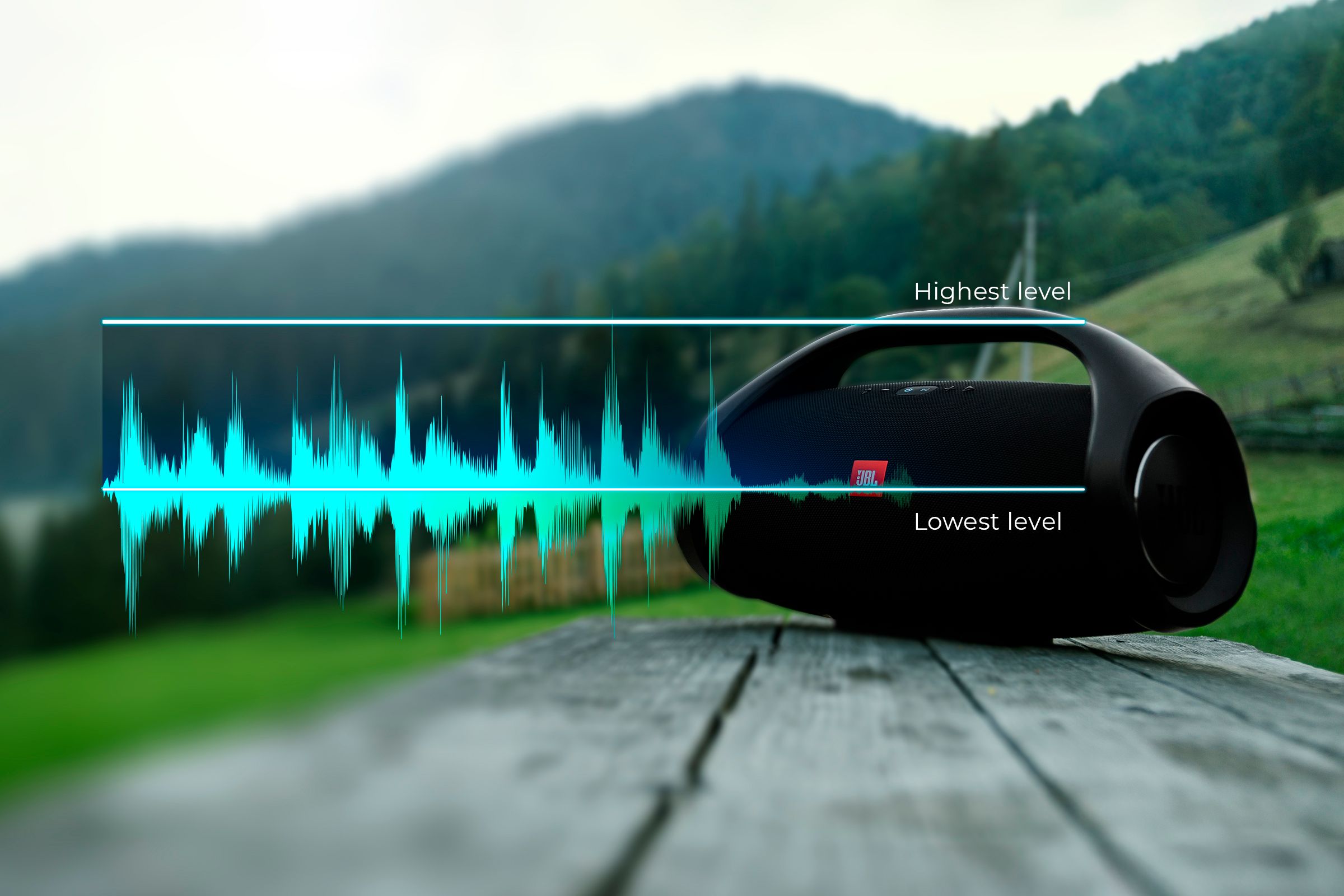

Bit depth defines the dynamic range—the difference between the loudest and softest sounds. A higher bit depth, like 24-bit audio, preserves more nuances than the 16-bit standard of CDs.

When audio is compressed into lossy formats, it’s often reduced in both sample rate and bit depth, which can eliminate quiet background details and result in a “harsh” or “grainy” texture.

Of course, with cheaper storage, more powerful processors, and better compression algorithms that vary the bit-rate based on what’s needed by the music at a given moment, the original quality of the music can be almost completely preserved. All while using just a fraction of the storage space of something like FLAC.

You Can Hear Poor Compression Easily

Even if you’re not an audiophile, poor compression can be noticeable. Common audio “artifacts” include:

- Clipping: Loud sounds become distorted or cut off.

- Metallic sound: A “tinny” quality from over-aggressive compression.

- Loss of dynamics: Music sounds flat and lacks impact.

- Echo or warble: Subtle distortions in vocals or sustained notes, similar to “wow” or “flutter” on vinyl records and cassettes.

Want to hear it for yourself? Compare a high-bitrate MP3 (e.g. 320 kbps) to a low-bitrate version (e.g. 128 kbps). The difference is stark, especially with complex music like orchestral or live recordings.

However, moving to higher bit-rates quickly sounds the same, which means that there’s a sweet spot, with 320kbps being a good example for MP3 specifically.