On top of being convenient and community-driven, Steam is perhaps best known for its incredible sales events. Now imagine a world where hyper-competitive online digital marketplaces don’t exist.

Steam makes it easy to expand your backlog and build up a huge library of games, but gaming on the cheap wasn’t always this easy. Here’s how we saved money back in the day.

PC Gaming Before Steam

Valve’s Steam client was officially released on September 12, 2003. I would have been about 16 at the time, and I have the “21 Years of Service” badge on my Steam profile as a constant reminder. In the early days, things weren’t so rosy. The client was slow, buggy, and had a very small selection of games.

Steam ushered in a new way of doing things: a digital distribution network for games at a time when many of us were still stuck on slow dial-up connections, and a friends list that was nice in theory but hardly ever worked. There was a server browser baked into the client, which sounds great on paper, but third-party server browsers already existed and were far better. The pushback against Steam was significant.

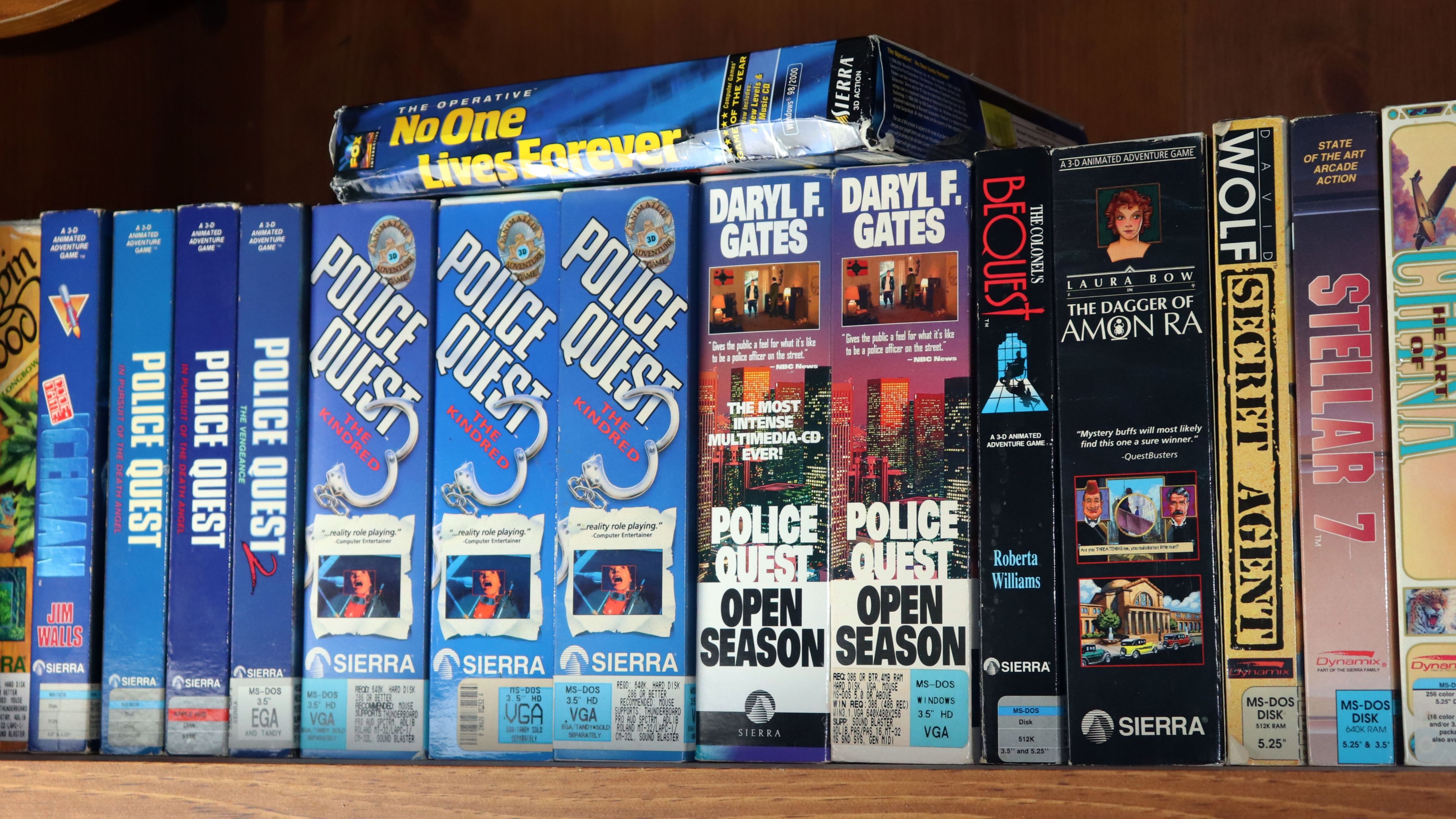

Half-Life 2 was the main reason a lot of people jumped on the Steam bandwagon, and that’s why I turned up too. While many of us unknowingly volunteered for an experiment in all-digital PC gaming, we also had back catalogs of optical media and big box releases. While you might be under the impression that games were a lot cheaper back then, that wasn’t necessarily the case.

In 2002, the average PC game cost around $50 (about $89 in 2025), with Blizzard breaking new ground and releasing Warcraft III for $60 (that’s $106 in today’s money). I grew up in the UK and remember SimCity 3000 costing a whopping £40 (that’s £73 today) when it was released in 1999.

Gaming was expensive, even by today’s standards. That’s why finding ways to save money was vital, especially if you were still in school with virtually no real purchasing power. You’d have to carefully use birthday and other gifting occasions wisely, or get your kicks for free.

Lots of Free Multiplayer Mods

Game modifications, or “mods” for short, are still one of the greatest parts of PC gaming (and they’ve even made their way over to consoles too). Mods range from small tweaks that affect minor game behaviors or swap out character models right through to total conversions and standalone releases.

The best thing about mods is that they are (usually) free, and this gave life to some of the most popular games of all time back in the day. Counter-Strike started life as a free multiplayer total conversion for the original Half-Life, gaining traction around the turn of the millennium before seeing a 1.0 release, a boxed retail release as Counter-Strike: Condition Zero, and a final release with version 1.6 that fittingly dropped alongside the Steam client.

Counter-Strike and Day of Defeat were my own personal favorites, and I even moved on to the Source variants during the early days of Steam. Team Fortress Classic is another capture-the-flag style game of the era that still enjoys a faithful following. But there were so many other fledgling mods that were created, maintained, and released all for free.

These included weirdo mods like Science and Industry which was a simple game of protecting assets (scientists) in a two-team deathmatch, Natural Selection which pitted marines against aliens in some of the best multiplayer maps ever, and Action Half-Life which aimed to simulate fights that would take place in an action movie.

Even after Steam hit the scene, mods like Source Forts (a fort-building masterpiece), Insurgency (a milsim shooter that is now a standalone franchise), and Garry’s Mod (a cultural phenomenon meme-machine) occupied a lot of my time. And they didn’t cost a thing. Mods were one of the best ways to extract more value out of the games you already owned.

While free mods still exist, gaming is far more mainstream than it once was. The rise of indie games makes it more viable than ever to create games from scratch and get paid for it, a strategy that can be lucrative yet hard to emulate. Modding on a grand scale is certainly still a thing, with projects like Fallout: London and Skyblivion proving what is still possible, but much like the internet as a whole the modding scene doesn’t feel like the Wild West anymore.

Mail Order

While the internet went mainstream in 1995 and rapidly gained ground throughout the late 90s and early 2000s, not everyone jumped on the online shopping bandwagon. For many, mail order was still the way to go right through to the mid-2000s (as was ordering with a credit card, over the phone).

Tucked into the back of gaming magazines would be retailers that undercut the prices you’d find in brick-and-mortar stores. Shipping was generally a single low price, so you could load up on a few games and still save some money compared to buying in-person from a chain retailer. Mail-order-only, and eventually online-only, retailers were the best source of cheaper new releases for this reason.

I remember buying games using this method as far back as the early 90s when I’d order big-box Amiga games by cutting out the order form in a copy of Amiga Power or The One, get my dad to write a cheque, and wait patiently for 7-14 business days for games to show up. This is how I got my hands on PC games like Carmageddon and Worms Armageddon.

Game Retailers (Especially Independents)

Video games truly hit the mainstream in the 90s, with the success of consoles like the Game Boy and eventually Sony’s PlayStation. As a result, many more retailers got on board. These were often the sorts of places you’d go to buy music or electronic goods, but occasionally dedicated stores would appear.

Independents were almost always the better choice as they stocked a huge number of games for a large variety of platforms. The next town over from where I lived had one such store, and I have fond memories of walking past the Sega Genesis and Game Boy sections into the PC gaming basement, a dusty room that was filled with oversized boxes and bins of what we’d now refer to as shovelware.

Brand new released and lightly used copies dotted the shelves. I remember walking away with games that I’d eventually play to death like Colin McRae’s Rally and Need for Speed II. I once returned to the store with a copy of Driver that I’d begged my parents for because it wouldn’t boot on my PC, only to swap it out for Unreal Tournament which worked a treat thanks to Epic’s inclusion of a software renderer.

These really do feel like the good old days, but much of it comes down to nostalgia. There’s no way a 45-minute drive and 2000’s game prices can compete with the immediacy, game selection, and bargains you’ll find on Steam in the modern era.

Shareware

Shareware was devised as a solution to software piracy in the 80s, but the phenomenon really established itself among gamers a decade later with the release of games like id Software’s DOOM. Rather than discouraging people from copying their wares, id embraced the practice by distributing shareware versions of its games that included only the first episode of four. To keep playing, you’d have to buy the registered full version.

I distinctly remember finding a treasure trove of shareware on a Duke Nukem 3D CD that helped me discover and play limited versions of Rise of the Triad, the original 2D Duke Nukem games, Whacky Wheels, and other Apogee classics. Though I couldn’t buy these games at the time because I was just a kid, they still kept me entertained and they’re still fun to revisit.

At the time, passing around floppy disks and CDs with shareware versions of games on them was fairly normal. The same was true of trial versions of software like PaintShop Pro, Adobe Photoshop, and Macromedia Flash.

Buying and Trading With Friends

Physical media advocates will be the first to tell you that being able to do exactly what you want with a game that you own is more important than ever. While PC gaming has become exclusively digital, the openness of the platform generally means this isn’t an issue. But one thing that Steam doesn’t support is game trading.

As Sony’s famous Official PlayStation Used Game Instructional Video demonstrated, sharing physical games was as easy as passing a copy from one person to the other. While you can share your library of Steam games with others, you can’t straight up sell a game you don’t like or are bored of to fund another purchase.

Related

How to Enable Steam Family Sharing (and What It Does)

Share your whole Steam library, or restrict access to certain games.

I borrowed PC games like Dark Forces II: Jedi Knight, Medal of Honor: Allied Assault and MDK and lent out my own copies of games, but resale was also always an option. By far my best score was a mint copy of Mafia for £10 shortly after release from a friend who decided the game wasn’t for him. That was a lot of money for 15-year-old me, but it was a 75% discount on the full price.

Demo Disks

Saving money and buying games for cheap aren’t necessarily the same thing. One thing I was lucky to enjoy while growing up was a subscription to my favorite gaming magazine (UK-based publication PC Zone). An upshot of this was the inclusion of a demo disk every month, which was a window into the world of new releases at a time when downloading these demos wasn’t feasible.

While game demos have made a bit of a comeback, they’ll probably never return to the dizzy heights of the late 90s and early 2000s. Not only did this give you something new to play every month, it was a great way to tell if a game would run on your hardware and whether it was any good.

This is how I knew that Unreal Tournament was playable, even if it was via software rendering. These disks helped me discover weird games I might otherwise have missed, like Monolith’s Shogun: Mobile Armor Division. Sometimes you’d even get standalone experiences, like the famous Half-Life: Uplink demo that’s a whole self-contained episode.

While it’s nice to look back on a time that’s impossible to return to, it’s also important to keep an eye on how good we’ve got it. Even at a time when new games are approaching the $80 mark, there are lots of ways you can save money on games.