Intel is talking a big game when it comes to taking back leadership in chip manufacturing, according to a new report which cites one of the company’s Vice Presidents.

That would be Ann Kelleher, VP and Technology Development General Manager at Intel, who as Bloomberg (opens in new tab) reports, said in a press briefing that when it comes to Team Blue’s targets in this respect: “We’re completely on track,” adding that, “We do quarterly milestones, and according to those milestones we’re ahead or on track.”

This backs up CEO Pat Gelsinger’s declared ambition to retake leadership in terms of production muscle, and as Bloomberg notes, Kelleher’s tech development team is trying to make up ground lost in past delays by stepping up efforts to introduce new processes at an ‘unprecedented’ pace.

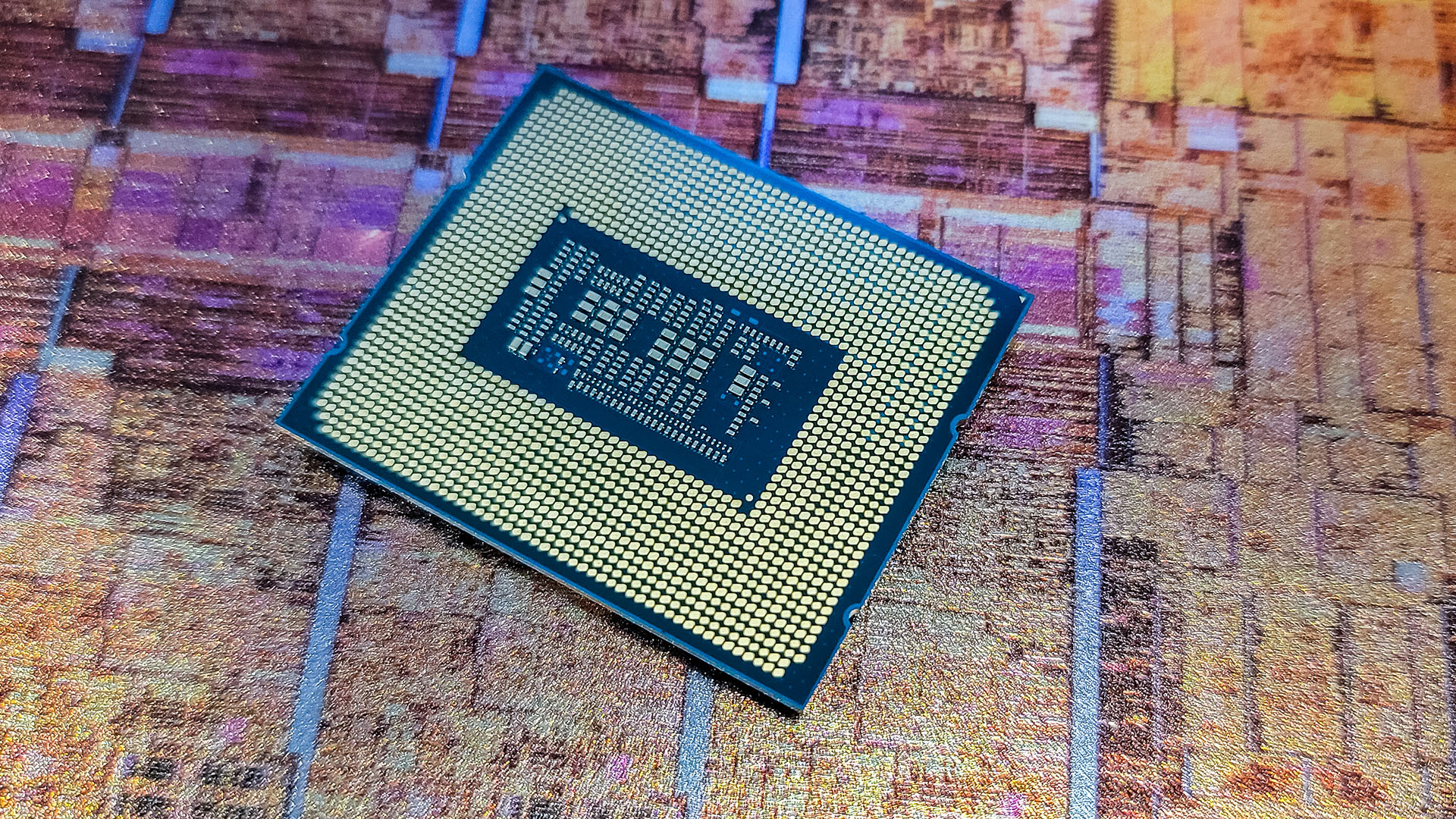

The idea is to take back market share from AMD, for one thing, which has gained popularity in recent history – particularly in the desktop arena – with some highly competitive Ryzen processors. Although Team Blue has already turned a corner in that battle after its markedly successful transition to hybrid tech with Intel Core CPUs (using a mix of performance and efficiency cores, first introduced with Alder Lake, the generation before current Raptor Lake chips).

More broadly, Intel wants to crank up its chip production capabilities to take on TSMC and Samsung in this sphere. Those are firms that make chips for a variety of big tech companies (like Apple for example), and Intel intends to compete in the space of producing chips for big-name clients, too.

In terms of the pace of process advancement, Kelleher observed that Intel is mass-producing 7nm chips now, and is ready to start with 4nm – with a move to 3nm due in the latter half of 2023.

Analysis: Shaking off the specter of past delays

The past still very much haunts Intel in terms of delays of CPUs built on new processes, such as the well-documented battle for 10nm, which witnessed Team Blue ending up stuck on 14nm for way too long. (Intel dropped to 14nm in 2014 then produced refresh upon refresh of that process as it failed to realize 10nm, and indeed Rocket Lake in 2021 was still using 14nm).

And part of the ghosts still rattling around from that episode is those previous promises that 10nm would be delivered, such as an assertion that it was on track in 2018 which turned out to be completely off the mark.

However, this time around, the posture and terminology used are very much more confident, rather than the defensive stance adopted around 10nm. It’s notable that Kelleher doesn’t just say that Intel is on track, but actually ahead of schedule for progress made with the moves to new processes in some respects.

Intel certainly seems to have had a long, hard look at the whole of its chip development and production capabilities. Kelleher also talks of taking new angles in terms of implementing contingency plans to ensure that any big delays are avoided – and rather than Intel trying to do everything itself, relying on equipment vendors to help out. Kelleher observed: “Intel in the past had high walls in terms of not sharing. We don’t need to lead in everything.”

The next step for Intel is Meteor Lake, which is its 14th generation to follow on from Raptor Lake, and that’s finally on 7nm. This update from Kelleher effectively gives us confirmation that those next-gen processors are on target for launch next year. Exactly when Meteor Lake will blaze into existence, and in what form, we don’t know yet. But rumor has it that Intel is focusing more on efficiency, even if that means 14th-gen chips could max out at 6 performance cores (and have more efficiency cores than Raptor Lake).

The overall plan (sprinkle seasoning here) might be to bring in Meteor Lake for laptops (where that efficiency really shines), and lower-end to mid-range desktop CPUs, leaving the 8-core Raptor Lake flagship and its higher-end desktop counterparts still in place, until they’re succeeded in the following generation. (That’ll be Arrow Lake, which could follow hot on the heels of Meteor Lake, going by rumors – whispers that could well be true if what Kelleher is asserting here proves to be correct in the course of time).