It’s been a rough decade for the Mac Pro. In 2013, Apple released a weird cylindrical model that didn’t meet the needs of most of Apple’s professional customers and wasn’t really upgradeable. In 2017, Apple called a bunch of tech journalists into a room and reaffirmed their commitment to the Mac, promising a new Mac Pro. That Mac Pro shipped in late 2019… less than two years before Apple made the announcement that it was shifting the Mac off of Intel and onto its own processors.

Just short of the 10th anniversary of that first Mac Pro misstep, Apple is now late in concluding its processor transition by shipping the first Apple silicon-based Mac Pro. What’s worse, reports from Bloomberg suggest that the company has ditched the next Mac Pro’s highest-end processor, calling the computer’s entire purpose into question.

Is Apple rethinking its commitment to the Mac Pro? And, given the many powerful characteristics of Apple silicon Macs, should it?

Niche of a niche

Let’s start with the facts: Almost nobody buys Mac Pros. The Mac is roughly 10 percent of Apple’s overall business, and it’s safe to say that at least 75 percent of Mac sales are laptops. That leaves a fraction of a fraction to be fought over by the iMac, Mac mini, Mac Studio, and Mac Pro. It’s pretty unlikely that the one that starts at $6,000 is going to be a large portion of those desktop sales.

But just because the Mac Pro is a niche product within a niche category within a small corner of Apple’s overall business doesn’t mean it’s not important. The arguments for Apple to keep a powerful expandable desktop at the top of the Mac line are numerous. Obviously, some markets simply require powerful, modular, expandable systems–and if Apple can’t provide them, they’ll lose out on those sales. (And if a market switches from the Mac at the high end, it’s possible that the rest of the computers in that market will also go from Macs to PCs.)

Then more broadly, there’s the “flagship” argument: The high-end Mac shows off everything the platform is capable of. Apple might not sell many of them, but their existence helps the Mac platform as a whole. And perhaps, as with the tech NASA developed for the Apollo program, Apple’s work pushing the very high end of Mac performance will create spin-off value that will accrue to the rest of the product line.

Or as Apple’s Phil Schiller said back in 2017:

Mac Pro is actually a small percentage of our CPUs — just a single-digit percent. However, we don’t look at it that way. The way we look at it is that there is an ecosystem here that is related. So there might be a single-digit percentage of pros who use a Mac Pro; there’s that 15 percent base that uses Pro software frequently and 30 percent who use it casually, and these are related. These are not distinct little silos. There’s a connection between all of this.

That’s Schiller explaining that the Mac Pro is valuable because… well, because it’s connected to the people who use Pro software a little and who use Pro software a lot, and… it’s all related, I guess? It sure seems a lot squishier when you think about it.

Apple doesn’t sell Mac Pro in numbers that compare to MacBooks, but it’s still an important platform.

IDG

The Mac Pro isn’t a product you make if the bottom line is all you care about. It’s the kind of product you make because you want it to burnish your reputation, to use it to boast about your prowess in designing computers and the chips that go in them. You make it because the experts in key fields want you to, and you love highlighting how your computers are used in those glamorous or exciting fields. You make it because “there’s a connection between all of this,” whatever this is.

Apple silicon doesn’t fit

Here’s the problem with the Mac Pro on Apple silicon: Apple has spent more than a decade designing mobile processors to be power efficient, to share a fast pool of memory between CPU cores and GPU cores, and to integrate Apple-built GPU cores inside the same chip package. It’s a model that was made for the iPhone, but it turns out that it scales pretty well to the iPad and, as we’ve discovered over the last few years, even to the Mac.

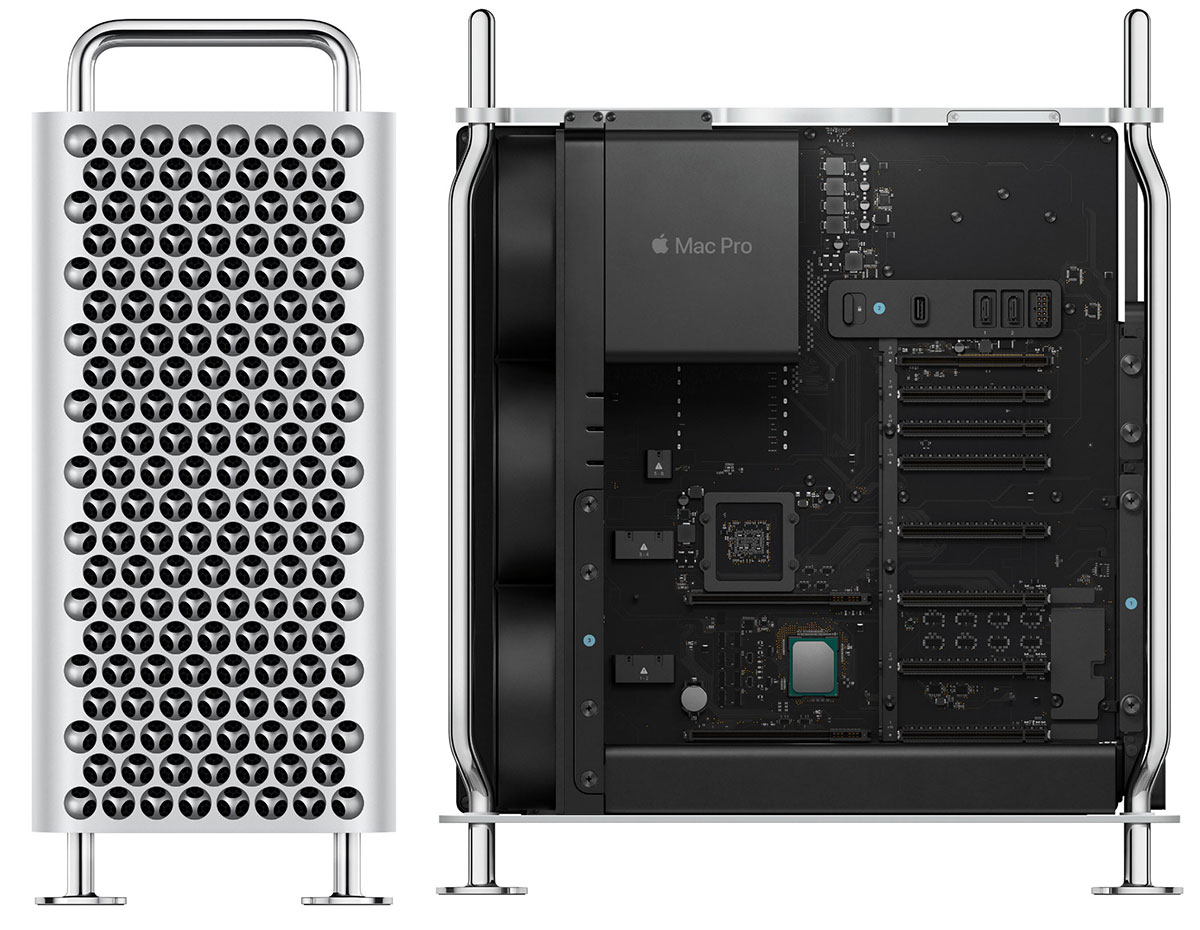

That’s great, but the Mac Pro doesn’t want to be any of that. It doesn’t want to learn any of those lessons. A big tower Mac doesn’t worry about energy efficiency. It’s got huge cooling fans and is plugged into the wall. It wants expansion slots to load in more GPU horsepower. It wants loads of expandable memory. It wants what Apple silicon was never designed to provide.

This is not to say that Apple couldn’t redesign things to fit the Mac Pro. But… do you re-think fundamental design decisions of the processor architecture that has led you to great success in phones, tablets, and all the other Mac models, all for a niche of a niche? This is one of the key questions of the next Mac Pro: Did Apple bend its chip-design philosophy for the Mac Pro, or did it bend the definition of a Mac Pro to feature its chips?

I can’t say that I’m encouraged by Mark Gurman’s report at Bloomberg that Apple has scrapped plans for an “M2 Extreme”, essentially four M2 Max chips (or two M2 Ultra chips) put together, which was originally planned to power the new Mac Pro. If Gurman is right, it means that the new Mac Pro will be powered by the next generation of the M1 Ultra chip that was introduced in the Mac Studio last year.

Minimal Mac Pro

So what makes a Mac Pro a Mac Pro? If it’s a tower enclosure, Apple’s got a relatively fresh one from 2019 that it can just roll out again. (Gurman says that’s now the plan, which is also a little disconcerting when you consider that the original reports suggested a new, half-height enclosure and that quad-M2 chip.) But what’s inside the Mac Pro matters, and if it’s just an M2 Ultra chip, it’s hard not to consider the new Mac Pro just a Mac Studio that moved out of its apartment and into a mini-mansion.

Does it help if there’s expandable internal storage? Sure, I suppose–it’s certainly a lot neater than attaching drives via external ports. Does it help if Apple offers additional M2 GPU cores via some sort of proprietary add-on card system? Maybe, if it’s done the extra engineering work. What about RAM expansion? Sure, but again, such a choice would undercut the work Apple has done to create a pool of fast, shared memory right next to the CPUs and GPUs.

And all that custom work, all those distortions to what makes Apple silicon so successful, would be done for a product that’s a niche of a niche–and it’s work that Apple’s chip design team could have spent on a next-generation chip for the iPhone, iPad, and Mac.

Apple

The final countdown

Is it worth it? I honestly don’t know the answer. It’s hard to imagine that building a new Mac Pro that’s anything but a big Mac Studio is worth it in terms of chip-design resources and money. But as much as I am baffled by Schiller’s statement in 2017 about everything being connected, if decision-makers at Apple truly believe it, then it’s the best case I can find for building one.

The danger here is that Apple’s forcing itself to build a computer that doesn’t really make financial sense, and along the way, it’s reduced the scope of the project to the point where the final product will also be a computer that nobody really wants to buy. That’s bad for all concerned.

But as harsh as I’ve been in this article, I’ll say this: I want Mac Pro users to be happy. I want the new Apple silicon Mac Pro, when it finally arrives, to justify Apple’s promises back in 2017. I’ve just got a bad feeling that the Mac Pro and the Apple silicon era aren’t as compatible as we were all hoping they’d be.