James Howells is someone we’ve reported on a few times in the past. Back in 2013, Howells had a significant collection of 7,500 bitcoin stored on a hard drive. That collection ended up in the trash and subsequently taken to a local landfill. For over 10 years it’s sat somewhere in the midst of that pile of waste—now Howells is taking his local authority to court to get it back.

Even at the time of the bitcoin’s disposal it was worth a pretty penny—today it’s worth around £500 million.

That’s a sum of cash that would be undeniably difficult to just let go of. Though the promise of such a booty has also become a powerful tool in earning Howells help from various legal teams and data recovery engineers—reportedly working pro bono for a slice of the bitcoin millions.

The case is currently being fought at Cardiff civil and family court, which is dealing with Newport City Council’s bid to ditch the case before it reaches a full trial. Howells wants to take the case to court to retrieve what he believes is still his legal property.

James Goudie KC representing the authority suggests (via The Guardian): “Anything that goes into the landfill goes into the council’s ownership.”

Meanwhile, Dean Armstrong KC representing Howells said (via the BBC): “we seek, plainly and candidly, a declaration of rights over the ownership of the bitcoin.”

Armstrong also noted the search would be a “precise excavation” of a “small area which we have been able to identify.”

There’s a lot of, probably fair, references to ‘needles in haystacks’. Though Armstrong also argues they’ve whittled down the haystack to a much smaller haystack and would be able to identify a smaller location where they believed the drive to be.

Ahead of the case, a Newport City Council spokesperson said (via South Wales Argus): “The council has told Mr. Howells multiple times that excavation is not possible under our environmental permit, and that work of that nature would have a huge negative environmental impact on the surrounding area.”

Howells, of course, disagrees with this statement, saying he has a team ready to go that could excavate a landfill within environmental guidelines and at no cost to the public, which has been another concern in this case. The council argues even dealing with Howells’ claims are costing the taxpayer money, and Goudie adds “Bitcoin enthusiasts are not above the law.”

Howells had previously offered to give the council £50 million if he discovered the hard drive and could recover the bitcoin fortune. At that time, it was worth about half of what it is now. Bitcoin’s value has surged massively in recent months as investors try to rally the cryptocurrency (if you can even really call it that anymore) over $100,000. They have not succeeded yet and Howells’ lost fortune has not yet become a lost billion.

A single bitcoin is currently worth around £75,000 ($96,000). Back in 2013, a single Bitcoin was worth around 1/1000th of that.

The judge has not yet passed a judgement on whether this initial case will go to a full trial—probably wise to weigh up the options.

Though you have to wonder what sort of state a hard drive would be in after 10 years being buried in a dump.

There’s surely some argument to be made that, after a time, the trash becomes almost an insulating layer on itself. Layers of layers of trash protecting the bitcoin millions like layers of pasta sheets protecting a lasagna’s meaty filling. Though you dread to think of the oozes and gunks in any city’s landfill site. Even with the best recycling systems in the world (Wales is pretty good on the ol’ recycling front) some perishable goods must’ve gotten through into that landfill over 10 years.

But doth a goo ruin a hard drive?

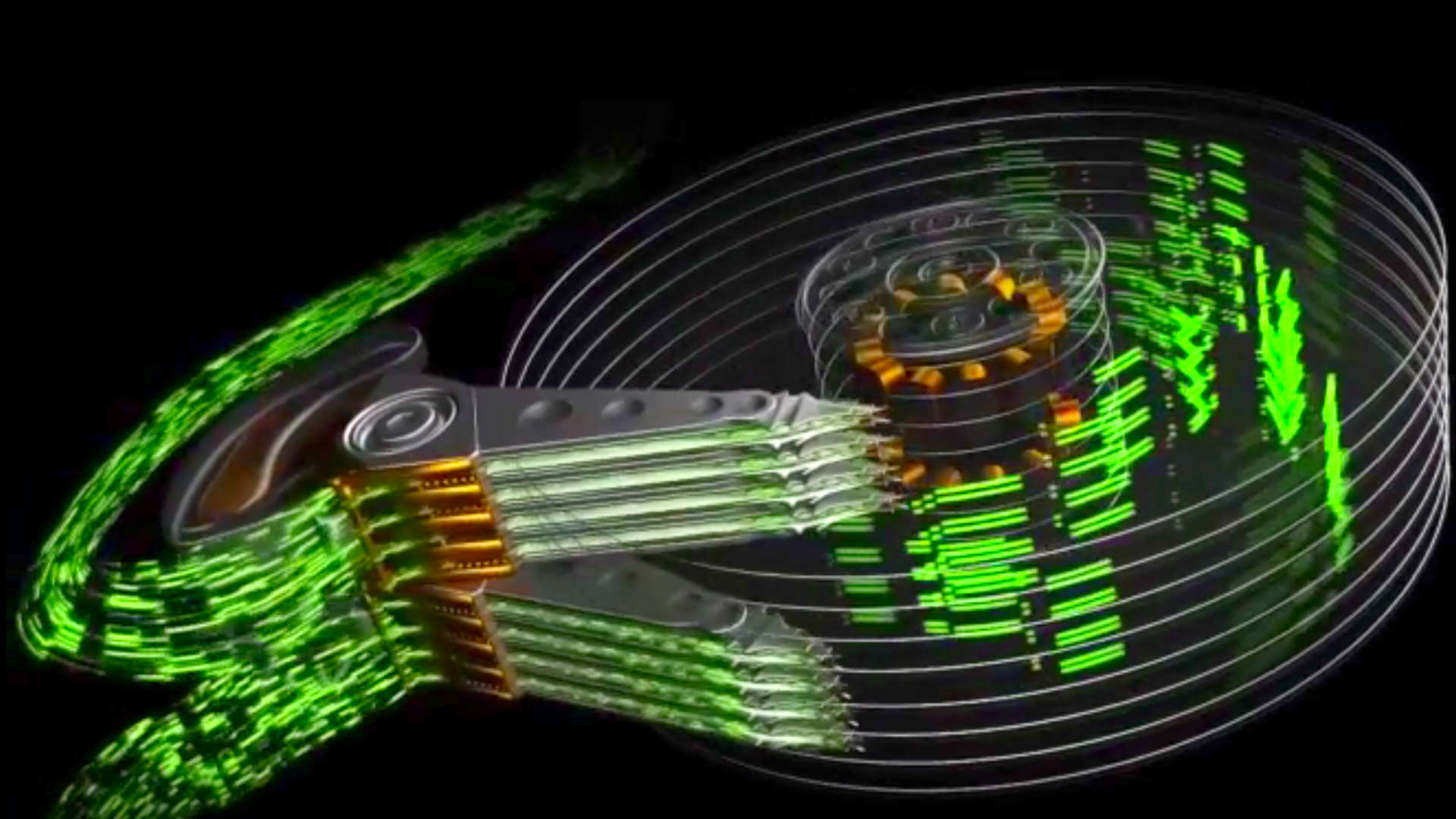

While generally seen as more susceptible to complete malfunction in a user’s PC compared to a more modern solid state drive, that’s largely because the HDD has a spinning platter with moving parts. A solid state drive is, you guessed it, solid. A HDD’s spinning bits might break, but you don’t need those to work to recover the data remaining on the drive.

The outer casing of a hard drive could be ruined, even the head damaged, and a professional might be able to do a good job of getting some of the stuff of it. Especially a drive that’s not been actively wiped. It all depends on the type of hard drive it is, how many platters it uses, and if any or all of the platters have been significantly damaged. Only the bits without damage can be recovered but that’s still potentially a whole lot of usable data.

The good news is, a hard drive is a pretty robust design—a big metal box surrounding layers of platters that sort of protect one another—again, like a lasagna—so maybe Howells and his team of pro bono experts are in with a chance. Now to find and prove in law that he still owns it—does one own their trash once the binmen take it away?