Summary

- Meteor origins are diverse, ranging from asteroid collisions to comet debris, each with varying compositions.

- Meteorites are primarily stony chondrites, but also include iron-rich achondrites and pallasites.

- Studying meteors provides insight into the universe’s early stages, from small rocky bodies to impactful events like craters and explosions.

The ancient Greeks thought meteors were fiery shooting stars originating from the tears of goddess Iris. They weren’t technically right, but meteors do produce quite a fiery spectacle in the sky as they enter the Earth’s atmosphere and burn up.

The Origin Theory

Humans have observed meteors for thousands of years, but for a long time they were associated with divine or spiritual portents. It was German physicist Ernst Chladni who first theorized that meteors are bodies of rock and metal that fall from the sky. Roughly eight years after Chladni’s controversial book on meteors was published, a chemical analysis proved that they were indeed extraterrestrial in origin.

So, how are they formed? Well, their origins are quite diverse. Some form when asteroids collide and chunks fall apart, while others are birthed within comet debris, natural satellites, or even planetary bodies. They are commonly stone-like, but some contain a lot of heavy metals such as iron—and there are hybrid varieties, too. The majority of meteors burn up completely in the atmosphere, so whatever falls on the surface is usually charred on the surface.

Related

I’ve Watched Many Meteor Showers—Here’s How You Can Too

There’s more to our sky than constellations and planets.

When the Earth passes through the trail of debris left by a comet, we see several meteors producing a dazzling effect in the sky, commonly referred to as a meteor shower. From our perspective, it seems as if all the meteors are coming from a single point in the sky, following a parallel trajectory. That’s also how they get their name, by tracing their relative point of origin to the closest star or constellation. The well-known Perseid meteor shower, for example, is named after the Perseus constellation.

What Are Meteors Made Of?

A majority of meteors that fell to Earth—and thus get the status of meteorites—are stony in appearance. Such meteorites are commonly referred to as chondrites, thanks to the presence of round grains called chondrules. These round grains are usually formed of minerals, which often get the appearance of partially molten droplets. As far as their formation goes, the NASA Astrobiology Program says gas-melt interactions triggered their formation.

According to a paper published in the Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta journal, chondrules went through the first physical change during their early phase after interaction with gases, leading to the formation of an outer layer surrounded by a silica-based matrix. But not all meteorites share the same chemistry or origin. As per the Lunar and Planetary Institute, achondrites (or iron chondrites) are formed in extremely hot and high-gravity situations. They are quite heavy, dense, and have a silvery appearance on the inside.

Then there are pallasites, which are a mix of heavy metals and silicate materials, and lunar meteorites, with their origins traced to impact events on the moon’s surface.

When meteors fall to Earth, they have an external layer called fusion crust, created due to the atmospheric friction melting their surface. Fresh samples are highly sought after, as they have not been altered by chemical interactions and Earthly processes. Meteors are studied predominantly to understand their chemical origin, which offers an insight into the early state of the universe.

An Impactful History

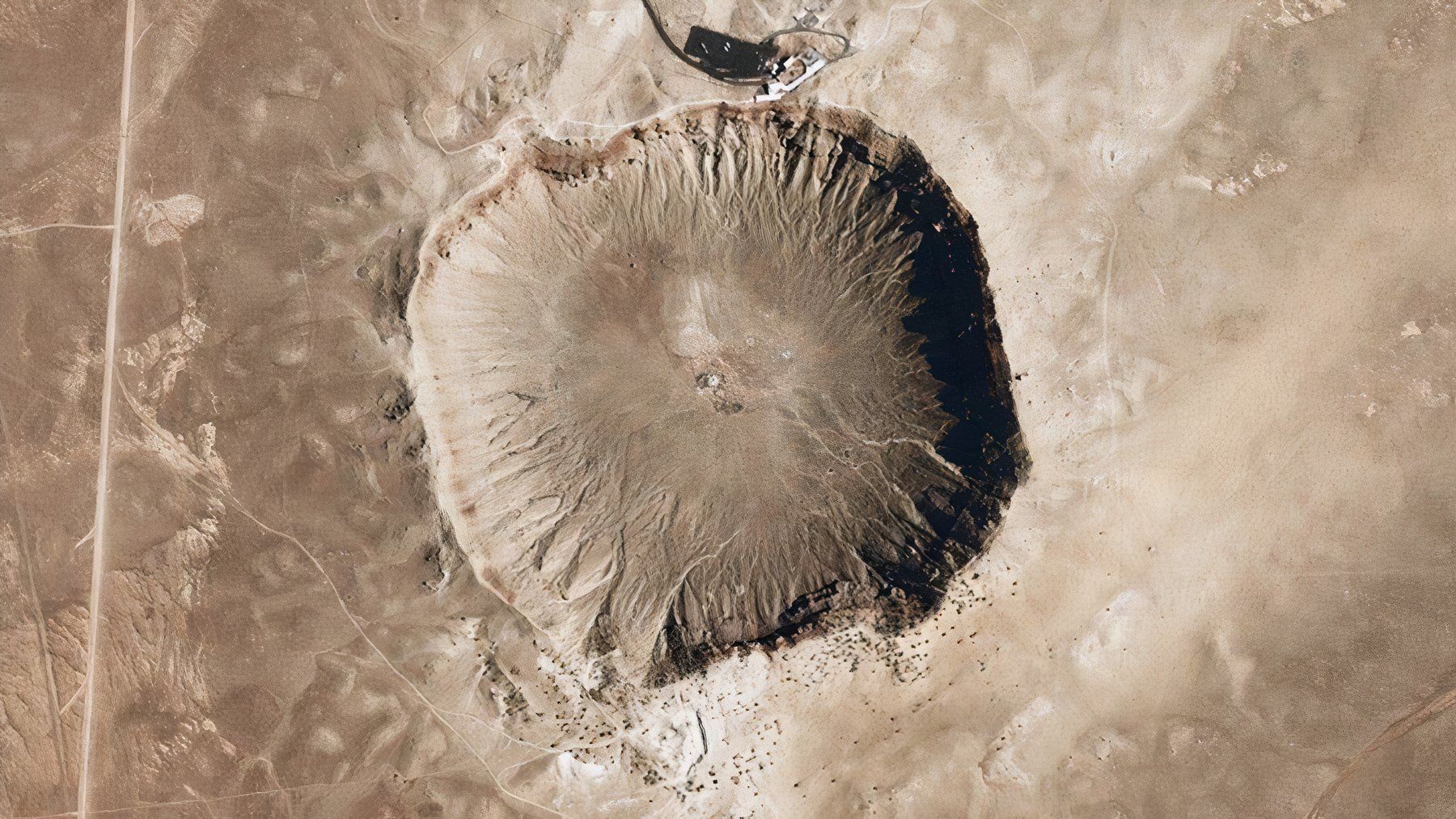

While most meteorites are small rocky bodies, a rare few left quite an imprint. The Barringer Meteorite Crater is about 0.6 miles across and was formed after an iron-nickel meteorite made an impact roughly 50,000 years ago. The impact event was so powerful that it created a rim of boulders that stand as high as 50 meters, while the crater’s depth is roughly 180 meters. When it was first discovered, tons of meteoritic iron were found in an area spread across 15 kilometres.

Elsewhere, the Tunguska event of 1908 triggered an airborne explosion so massive that it flattened trees in an area spanning hundreds of miles. The locals only saw a giant fireball, followed by a bright flash, and then a booming sound. The shockwave and heat blast from the explosion were so strong that the evidence of destruction was still intact when the first scientific expedition reached the zone nearly two decades later.

Then there was the 2013 meteorite event in Russia’s Chelyabinsk, which is estimated to have delivered a blast energy worth 440,000 tons of TNT explosion. It shattered windows in a 200-mile area and injured hundreds of people. NASA Planetary Defense Officer, Lindley Johnson, referred to the event as a cosmic wake-up call. On the same day, plans for an International Asteroid Warning Network (IAWN) and space Missions Planning Advisory Group were finalized at a UN meeting in Vienna.

Meteor Observation and Prediction

The size of meteorites varies dramatically. They can be grain-sized, or even weigh a few thousand pounds. The Hoba Iron meteorite, for example, weighs 66 tons. But they can also be amazingly small.

“Meteors fly by the ISS all the time, but the astronauts don’t see them. The meteor is just a little piece of rock, but it is so dark and moves so fast that you don’t see it whiz by,” says Bill Cooke, lead at the NASA Meteoroid Environment Office (MEO).

MEO is the NASA agency tasked with monitoring and providing meteor forecasts. The agency keeps an eye on meteors by keeping a track of larger bodies such as asteroids and comets that come close to Earth using ground-based telescopes. Using advanced simulation modes, the experts not only calculate the probable trajectory of these objects, but also predict when they might enter the Earth’s atmosphere.

Based on this information, the MEO also publishes an annual forecast of meteor shower predictions and other such events. Interestingly, the space agency has a dedicated program called NASA’s All Sky Fireball Network that tracks fireballs, which are essentially meteors that are brighter than the planet Venus.

The system, which consists of 17 cameras with overlapping fields of view placed across the country, automatically updates its data and maintains a live view radar for all meteor events. The Canadian Meteor Orbit Radar is capable of detecting meteors that are as small as one millimeter across, while also calculating details such as their spatial location, speed, and direction.

NASA’s data presentation is rather technical. Thankfully, the American Meteor Society maintains a fantastic database of all upcoming meteor shower events, complete with date, time, peak, and radiant location details. For photographers or enthusiasts, NASA even offers learning material on how to click the best meteor shower shots.

Meteor showers are one of those rare but flashy cosmic phenomena that we can witness with the naked eye. Their origin is tied to rather unexciting materials such as rocks, dust, and ice, but their scientific analysis can offer a glimpse into an early state of the universe itself. That’s quite some existential history rooted in streaks of light appearing in the night sky, isn’t it?

Related

The 6 Most Interesting Facts About the Moon

Earth’s only natural satellite is endlessly fascinating.