What you need to know

- Microsoft shared a new report from the Microsoft Threat Analysis Center (MTAC) highlighting Russian influence operations in Africa, focusing on the Niger coup.

- The report indicates that Russia is using the internet to promote political instability worldwide to further its agendas.

- The MTAC has pinpointed six basic elements to Russia’s African coup playbook, including banning dissenting media, seizing control of the narrative, and more.

Political instability negatively impacts the development trajectory of a country. Besides the lack of adequate social amenities to cater to the public’s needs, high unemployment rate, and insecurity, investors also tend to shy away from venturing into any business activities in a country that’s in a volatile state.

While various avenues are being explored to counter the issue to achieve reprieve, it’s no easy feat. That’s especially true with huge income disparities.

Microsoft recently unveiled a new report from the Microsoft Threat Analysis Center (MTAC) on Russian influence operations in Africa, focusing on the Niger coup (even though the US refuses to call it one). The report unpacks how the Internet is being leveraged to promote political instability worldwide.

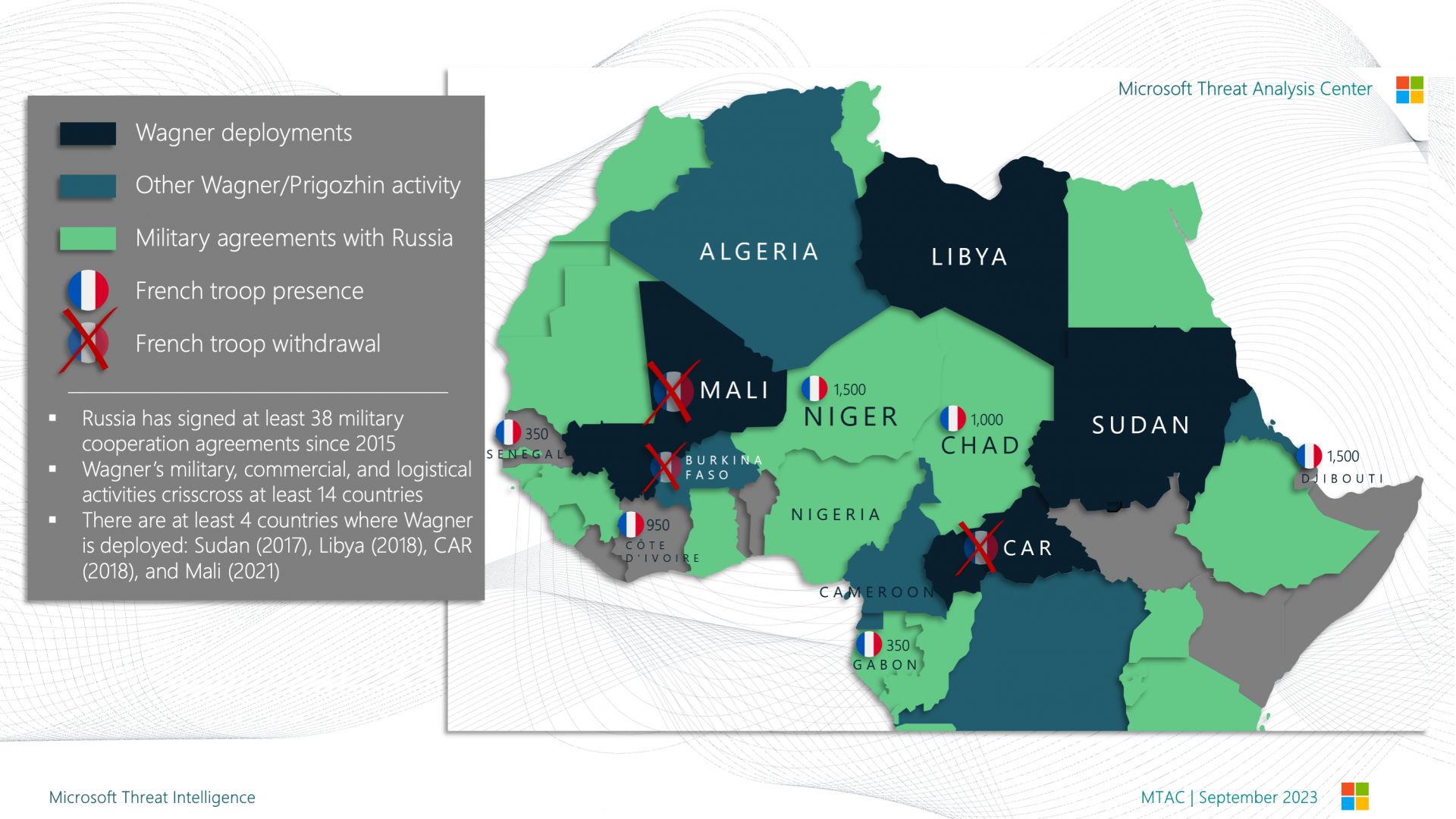

In the past few months, French-speaking African countries, including Mali, Guinea, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Gabon have experienced increased military coups. The countries highlighted above have been impacted by coups for nearly two decades, and the situation isn’t improving.

The appearance of Russian flags is symbolic of a multi-pronged media strategy Russia has developed to capitalize on coups. Although the power grabs in the Sahel and now Gabon were motivated by political dynamics specific to each country, Russia’s online and offline influence campaigns have acted as an accelerant, driving polarization and cementing the authority of often outwardly pro-Russian coup leaders.

MTAC

According to the report, Niger coup leaders leveraged their influence and power to suppress initial protests in Niamey, closing the capital and imposing a curfew restricting movement. This was swiftly followed by multiple counter-protests that supported the coup and brandishing Russian flags. The protests were in place to get the previous government back in power and see France depart from the Sahel region of Africa.

The MTAC highlighted several Nigerien civil society groups deeply rooted in these activities but listed PARADE Niger and the Union of Pan-African Patriots as the key players in the pro-Russian stance. “The first appears to be a construct of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs with little genuine local support while the second is a political vehicle for a single politician,” the report detailed.

The groups have been found to be in support of the coup and have even requested more cooperation with Russia. They’ve also assisted in coordinating and amplifying offline protests. Not forgetting the crude methods used to promote this content online.

MTAC also pointed out Russia’s African coup playbook in Africa and narrowed it down to six basic elements.

First, with the help of its messengers in Africa, Russia can curate a substantial amount of content that’s both anti-French and pro-Russian, centered on polarizing issues fueled by colonial-era issues.

Next up, Russia places itself in a strategic beneficial position whenever a coup occurs. This is why messengers with close affiliations to Russia align themselves with putschists and declare support for them through proxies.

There’s also the fact that Russia can amplify affiliates via its pro-Russian propagandists and IO networks, thus making it easier to push their agendas further. This is regardless of whether they are overt or covert. This way, it’s easier for them to wash down other narratives raised by other parties, ultimately selling their agenda as the popular agreement amongst the people.

Radio France International and France 24 are among the largest French-language sources of credible news from the West but have been banned from sharing stories with the public. Coup leaders, in collaboration with Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, got these credible media houses from the air since they weren’t pushing their narratives and agendas but reporting things as they were.

There’s also the inclusion of Russian flags in pro-coup protests designed to create a facade, fronting “widespread support for both the putsch and partnership with Russia.”

Finally, Russia can establish control of the narrative through its messengers who are aligned on prepositioned narratives right after the coup. This way, making the most out of the information gap is possible. “Post-coup messaging typically glorifies military and coup leaders and championing national sovereignty while denigrating France.”

Abstract online facade versus reality

Whatever’s portrayed online doesn’t directly reflect what’s going on in reality. External sources play a major role in determining the information fed to the public, regardless of accuracy. So long as they can push their agendas and narratives further, even if it’s at the cost of political instability across African countries.

To this end, it’s unclear what measures can be implemented to mitigate these issues and ensure that the information being relayed on the internet clearly depicts what’s going on in reality. But the information shared online should be taken with a pinch of salt.