To print this article, all you need is to be registered or login on Mondaq.com.

Decisions of the EPO Board of Appeal in 2023 can largely be

regarded as a continuation of the trends established in 2022. The

findings of

Enlarged Board Decision G1/19 from 2021 continue to

dominate, with an emphasis on the whole scope of the claim having a

technical effect and some popular earlier precedents being

overruled. Although we have not collected detailed statistics,

there seems to be increasing trend for Boards to refuse to admit to

requests on appeal, even to the extent of whole appeals being

rejected because no requests are admitted. New requests will only

be admitted on appeal in response to truly new circumstances, such

as unexpected new objections raised by the Board of their own

motion. Below we discuss cases of interest or perhaps general

applicability, highlighting some interesting cases relating to

artificial intelligence and digital therapeutics.

Statistics

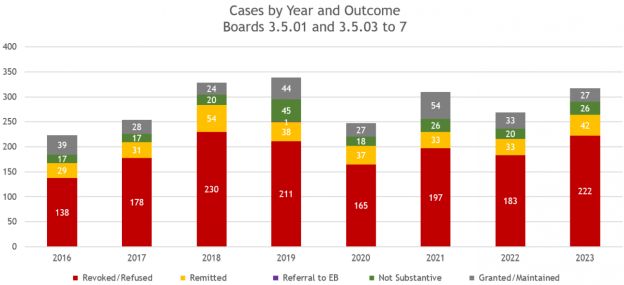

With 317 cases by Boards 3.5.01 and 3.5.03 to 3.5.07 in 2023,

there is a clear increase in output compared to 2022 but still no

return to pre-Covid levels and no apparent reduction in pendency

times.

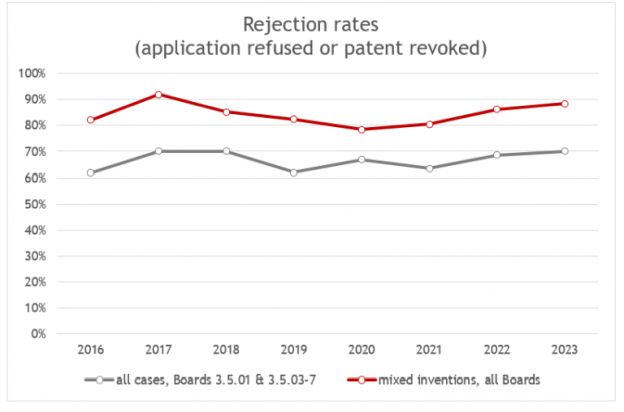

Overall, rejection rates remain high with 70% of cases resulting

in the application or patent in suit being refused or revoked. Of

those that do survive, there has been a slight shift towards

remittal for further prosecution (13%) versus grant or maintenance

(9%). The remaining decisions include cases where the appeal is not

followed through by the applicant, deal with purely procedural

issues, or all requests are rejected as inadmissible. Rejection

rates for these Boards at 70% are consistent with previous years,

as are rejection rates for mixed inventions across all Boards at

88%.

Artificial Intelligence

For a year in which artificial intelligence, in particular large

language models like ChatGPT, has been so prominent in the general

media, there have been remarkably few EPO appeal decisions relating

to inventions involving AI.

T 0183/21 (Controlling the performance of a recommender

system/BRITISH TELECOMMUNICATIONS) of 29-09-2023 perhaps

well illustrates the approach of the EPO to such inventions: in

general terms applying AI to a particular problem is not inventive

and applying AI to a non-technical problem does not in itself

confer technical character, but technical details of the solution

can be inventive. In this specific case, recommending products,

specifically media content, does not have technical character

(following

T 1869/08 and

T 0306/10). However, a technical effect to reduce the use of

network bandwidth to provide training data to the recommender

system and the storage necessary for storing training data was

recognised and “achieved, on average, over substantially the

whole scope of the claim”. This effect was achieved as a

result of a trade off with the achievement of a performance metric

that was not suggested in the prior art.

In spite of advancing every conceivable argument, the applicant

in

T 0761/20 (Automated script grading/UNIVERSITY OF

CAMBRIDGE) of 22-5-2023 was unsuccessful. The invention

related to “a method of automated script grading using machine

learning, which is effectively a computer implemented process. Such

processes may have technical effects – and thus be deemed to

solve a technical problem – at their input or output, but

also by way of their execution (see G 1/19, reasons 85). A

technical effect may also be acknowledged in view of their purpose,

i.e. an (implied) technical use of their output (see G 1/19,

reasons 137).” Most interesting are the discussions of

technical effects “within the computer” and by implied

use.

On the first point, the claimed method contains steps for

extracting numerical “linguistic” vectors from scripts, a

step of training a perceptron, and a step of using the perceptron

to grade the scripts. The extraction of linguistic vectors was not

detailed in the claim and therefore in the eyes of the Board

“cannot be considered to provide any contribution on its own,

be it related to the script acquisition (e.g. scanning or OCR) or

modelling, or to any optimization within the computer.”

The claimed perceptron model is a linear mathematical function

that maps input numerical vectors to output grades and the only

details claimed related to optimization of training to preserve the

ranking of grades, as opposed to minimizing the absolute error in

output grades. According to the Board, “[t]he model is not

based on technical considerations relating to the internal

functioning of a computer (e.g. targeting specific hardware or

satisfying certain computational requirements), and the preference

ranking is chosen merely according to its educational purpose,

which does not relate to any effects within the computer

either.”

On the second point, the applicant argued that the problem

solved by the invention, “providing a computer system that can

automatically grade text scripts [and provide grades] that

correlate well with the grades provided by human markers” is

technical. To decide whether this is technical or not, the Board

considered (i) whether this problem is, or implies, a technical

one, and (ii) whether it is actually solved.

On question (ii), “the Board remarks that the human grading

process is a cognitive task in which the marker evaluates the

content of the script (e.g. language richness and grammatical

correctness) to assign a grade.” They also noted that this

process “is also at least partly subjective: the marker will

have preferences as to style and language, and will be influenced

by experience and grades assigned to scripts in the past.”

Hence, they doubted “that the problem of automating script

grading is defined well enough that one can properly assess whether

it has been solved, i.e. in the sense that it provides a system

that can actually replace different human markers and provide

“correct” grades.

On question (ii), the Board ‘further notes that the field of

“educational technology” as defined by the Appellant …

is a rather inhomogeneous one, covering insights from – and

presumably contributions to – a wide range of

“fields”, technical ones and non-technical ones. It

appears questionable, therefore, that this field can be considered

a technical one as a whole.’

T 0702/20 (Sparsely connected neural

network/MITSUBISHI) of 7-11-2022 discusses neural networks

at some length and in particular the issue of whether an improved

structure of a neural network can provide a technical effect within

a computer. In this case, the difference between the claimed

invention and the prior art was that the different layers of the

neural network are connected in accordance with an error code check

matrix. The applicant asserted that this improved “the

learning capability and efficiency of a machine by reducing the

required computational resources and preventing overfitting”.

The neural network was not claimed in the context of any specific

technical problem. Refusing the application, the Board observed

that the “claim as a whole specifies abstract

computer-implemented mathematical operations on unspecified data,

namely that of defining a class of approximating functions (the

network with its structure), solving a (complex) system of

(non-linear) equations to obtain the parameters of the functions

(the learning of the weights), and using it to compute outputs for

new inputs. Its subject matter cannot be said to solve any

technical problem, and thus it does not go beyond a mathematical

method, in the sense of Article 52(2) EPC, implemented on a

computer.”

The Board’s “Further remarks” suggest that it will

be difficult to convince this Board (3.5.06) at least that a

general invention in the structure or training methods of a neural

network is technical. The Board says that neural networks must

“be sufficiently specified, in particular as regards the

training data and the technical task addressed.” To rely on a

technical effect “within the computer” would likely

require a limitation to specific computer hardware.

Although outside the scope of this paper, it is worth directing

attention to our briefings on two developments in the UK:

a final determination by the Supreme Court that an

artificial intelligence cannot be an inventor and

a finding by the High Court (said to be under appeal by

the IPO) that an artificial neural network is not a computer

program as such.

Whole Scope

The greater emphasis on ensuring that an invention meets the

requirements of the EPC across the whole claim scope continues

since G 1/19, even in fairly simple cases. For example in

T 1887/20 (Input device with load detection and vibration

units/KYOCERA) of 3-3-2023 the appellant argued ‘that

the haptic effect provided by the invention solved the problem

“to provide a realistic sensation of operating a push-button

switch”.’ However, the Board considered this aim not to be

met across the whole scope of the main request, which had no limit

on the duration of the haptic effect and so “encompasses

durations significantly longer than the time a push button is

typically pressed, thus providing feedback even when the button has

been released.” An auxiliary request that did include a limit

on the duration was however considered inventive.

The whole scope requirement is sometimes criticised as

unrealistic since it is almost always possible to find something

covered by a claim to an apparatus or method that does not work

(e.g. a claim to a teapot does not exclude that it is made of

chocolate), therefore the more nuanced approach taken by the Board

in

T 0814/20 (Adapted Visual Vocabularies/CONDUENT) of

20-3-2023 is welcome. The invention related to image matching and

was supported by a single embodiment directed to vehicle license

plate identification. Initial claims that specified measuring image

“similarity” were considered vague and not serving a

technical purpose. However, claims limited to reidentification of

objects in different images were considered to have a technical

purpose, “because it is tantamount to an objective measurement

in physical reality: is the object observed now the same as the one

observed earlier?”

The remaining issue was therefore whether the claim provided a

technical effect over substantially its whole scope. Having

accepted that the theoretical assumptions underlying the invention

were credible, the Board’s comments are helpfully

pragmatic:

‘The claimed method will not “work” under all

imaginable circumstances. It is probably safe to say that no

computer vision method does. For instance, the present method may

fail to re-identify objects largely changing appearance. However,

the skilled person will understand, from the present claims and the

description, the kind of situations and its parameters (such as

illumination and geometry) for which the method is designed. The

method credibly works over that range of situations.

In the Board’s judgment, this is sufficient to satisfy the

requirement that, in the present case, a technical effect is

present over substantially the whole scope of the claims (see again

G 1/19, reasons 82).’

One approach to an objection that a claim does not solve a

technical problem over its whole scope is to advance a less

demanding problem, or to phrase the problems as to be solved in

certain conditions. However,

T 1890/20 (Display Device/NEC) of 1-3-2023 makes it clear

that this strategy only works if the claims are limited to the

“certain conditions”. On the other hand, if a claim has

two distinguishing features and one credibly solves a problem

across the whole scope of the claim, it does not matter if the

other distinguishing feature does not solve a problem:

T 1573/21 (Determining Virtual Machine Drifting/HUAWEI) of

30-08-2023.

Inventive Step

Board 3.2.02, whose caseload normally relates to medical and

veterinary science, applied the Comvik approach in

T 2165/19 (Taste Testing System/ OPERTECH BIO, INC) of

05-12-2023 and took an interesting approach to the selection of the

starting point for an inventive step objection. The invention

related to “a device aimed at technically implementing a

taste-testing procedure in which a taste sample is presented to a

human subject for tasting and feedback is then gathered from the

subject”. It was noted that such a taste-testing procedure is

not of a technical nature per se (similarly to the odour selection

procedure discussed in

T 619/02) but what was claimed was a physical device adapted to

automate the method, which is technical. The Board considered that

the Examining Division had incorrectly applied the Comvik approach

based on a document that disclosed automated pipetting systems that

shared some physical features with the claimed device but for a

very different purpose: transferring defined amounts of liquids

between preselected groups of reaction containers.

The Board considered this document not to be an appropriate

starting point for assessing inventive step of claim 1 as the

skilled person would not have looked at this document without the

benefit of hindsight. Instead, the starting point for the invention

should be prior art in the field of devices and methods for

assessing a subject’s response to stimuli. Although the problem

to be solved was considered non-technical and therefore

“given” to the person skilled in the art, it seems

reasonable that it is not obvious to seek a solution to that

problem in hardware for a different purpose. At the same time, this

is consistent with many cases where general

purpose hardware is considered a suitable starting point

for implementation of non-technical methods.

General purpose hardware, such as computers and networks, are

often considered “notorious”, meaning that no specific

prior art disclosure need be cited.

T 1898/20 (Method and server for providing air fare

availabilities/SKYSCANNER) of 05-12-2023 warns that care

must be taken in asserting that something is notorious. The

invention here related to assembling data relating to air fares and

seat availability. The claims referred to a “distribution

system server” which implements specific functions. Although

the distribution system server was discussed in the prior art

section of the application, the applicant argued that these

mentions were not necessarily admissions of common general

knowledge. The Board noted that, in contrast to US Patent Law, the

EPC does not know the principle of admitted prior art and so could

not assume the distribution system server is notorious. Therefore

the case was remitted to the examining division for further

prosecution, in particular to carry out a search for a prior art

document disclosing the distribution system server.

There was a similar outcome in

T 2321/19 (Capturing user inputs in electronic

forms/BLACKBERRY) of 13-2-2023 where the Board agreed with

the applicant’s argument that it was very difficult, thirteen

years after the date of filing of the present application, to

assess what was the common general knowledge of the person skilled

in wireless hand-held devices at that date of filing, especially

since the technology of mobile phones had evolved very quickly at

that time. Since this aspect of the common general knowledge of the

skilled person was highly relevant, the case was remitted to the

examining division to allow for two-instance consideration of the

common general knowledge.

The scope of notorious prior art and common general knowledge

was also at issue in

T 1273/20 (Performance storage system/EMC) of 13-11-2023.

The Board observed that ‘no specific documentary evidence may

be needed to prove knowledge which belongs to the “mental

furniture” of the skilled person, such as routine design

skills and general principles of system design which are often

necessary just to understand the prior art in the relevant field (T

190/03, Reasons 16).’ And went on to conclude that

“[m]emory hierarchies are so pervasive in the computing field

that the board considers that no documentary evidence of them is

needed.” Contrasting with the two cases discussed above, it

was only the general concept of memory hierarchies that was

considered common general knowledge and sufficient to render the

claimed invention obvious, and not any detailed implementation

thereof.

The absolute novelty approach of the EPC implies that all prior

art disclosures are of equal potential as starting points for an

inventive step argument. In

T 1092/19 of 04-10-2023 the Board rejected an argument

that the person skilled in the art would not consider modifications

to a method described in a working draft of a video coding standard

because of the nature of that document, rather than based on

technical reasons. The Board commented “the person skilled in

the art is motivated by the desire for further improvement and is

not dissuaded from their pursuit by administrative decisions, e.g.

those taken by standardisation organisations.”

That an invention is a straightforward automation of a known

manual method is a fairly common reason for asserting a lack of

inventive step. However,

T 0302/19 (Cell characterization/BIO-RAD) of 21-12-2023

cautions that “[f]or such an argument to succeed, it should be

clear what is the alleged manual practice, it should be convincing

that it was indeed an existing practice at the relevant date and

that it would have been obvious to consider automating it.” In

that case, the detail was lacking and the alleged manual procedure

unconvincing as it would have been too laborious to carry out

manually.

J A Kemp LLP acts for clients in the USA, Europe and

globally, advising on UK and European patent practice and

representing them before the European Patent Office, UKIPO and

Unified Patent Court. We have in-depth expertise in a wide range of

technologies, including

Biotech and Life Sciences,

Pharmaceuticals,

Software and IT,

Chemistry,

Electronics and Engineering and many others. See our

website to find out more.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general

guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought

about your specific circumstances.