If you’re a UK home owner connected to the electricity or gas grid, it’s likely you’ve already been asked to install a smart meter.

Since 2011, energy suppliers have visited more than 21 million homes and small businesses to swap out old mechanical or electric meters for newer, connected ones, which give customers and energy suppliers more information about how and when we’re using energy.

In an era when energy prices are far higher than before, anything that helps consumers use less sounds like a great idea, but smart meters have proved divisive. There are privacy questions regarding the data gathered by their operators, with additional concerns about their role in forcing struggling consumers onto pre-payment plans.

Quite apart from anything else, the smart meter rollout hasn’t always gone smoothly. There have been repeated delays, so the programme’s behind where it should be. Worse, the first generation ‘SMETS1’ meters could lose their smart functions when customers switched supplier. And even if neither of those put you off, there’s the small matter of a few hours without power while you get a new meter installed.

Despite the potential benefits of a smart meter, many consumers wonder why they should bother – it’s not compulsory, after all. So what are the risks and benefits? We look at what the upgrade could do for you, and whether you should install a smart meter at all.

A smart solution?

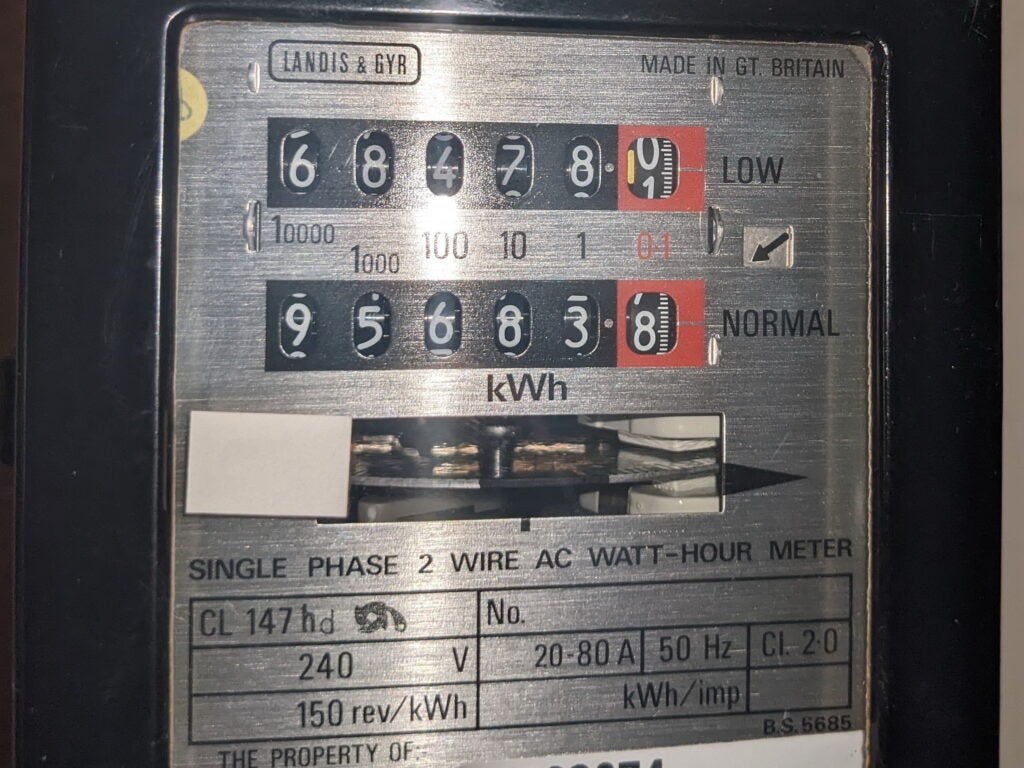

The groundwork for the smart meter rollout was laid in the Energy Act of 2008, and installations themselves began in 2011. Previously, energy meters simply measured the amount of electricity or gas being used by a home or business. They displayed the total, and needed to be read either by the energy supplier or the consumer. It’s a system that worked well for decades, but after gas (1986) then electricity supply (1990) was privatised, things got a little more complex.

As energy suppliers reduced the number of meter readers, they began to rely more on consumers’ own readings. When these weren’t forthcoming, they had to guess at a figure and bill accordingly, which could cause problems if the estimate was wrong, if there’d been a price change, or when customers switched supplier.

There’s another more pressing issue, caused by the changing use and generation of electricity. While we’re used to paying a flat rate for electric power, that doesn’t reflect what it actually costs to generate, which varies throughout the day according to supply and demand. The latter peaks from about 5-8pm on weekdays, but more than a third of UK power now comes from wind and solar, which are variable.

Keeping the grid balanced when supply doesn’t meet demand often means firing up polluting energy sources, or paying much higher rates to generators. This problem will only become more acute as the UK adds more renewables and, at the same time, more consumers switch over to electric cars and heating, increasing the overall demand for electricity.

In the future, more homes and businesses will have the technology to store off-peak energy for use during peak times, but for now, smart meters are an important tool in helping manage demand by encouraging customers not to use electricity at peak times. They let energy supplies see when their customers are using power, so they can charge more or less depending on how plentiful it is at that moment. And as we’ll see, this can be both a good and a bad thing.

How do smart meters work?

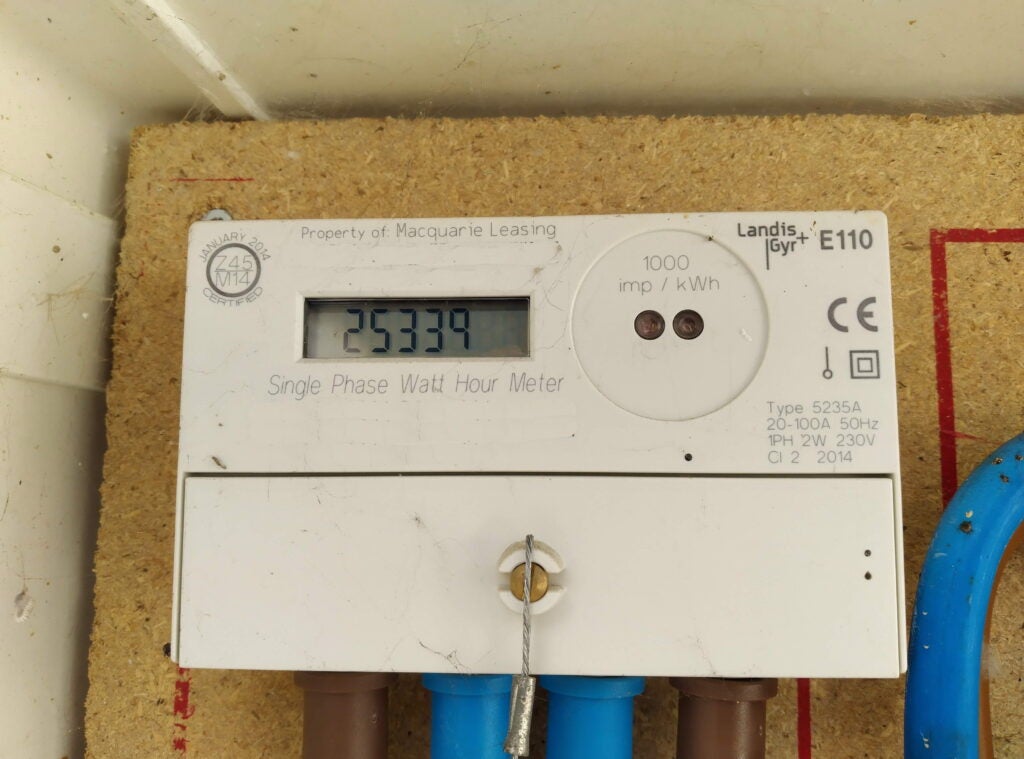

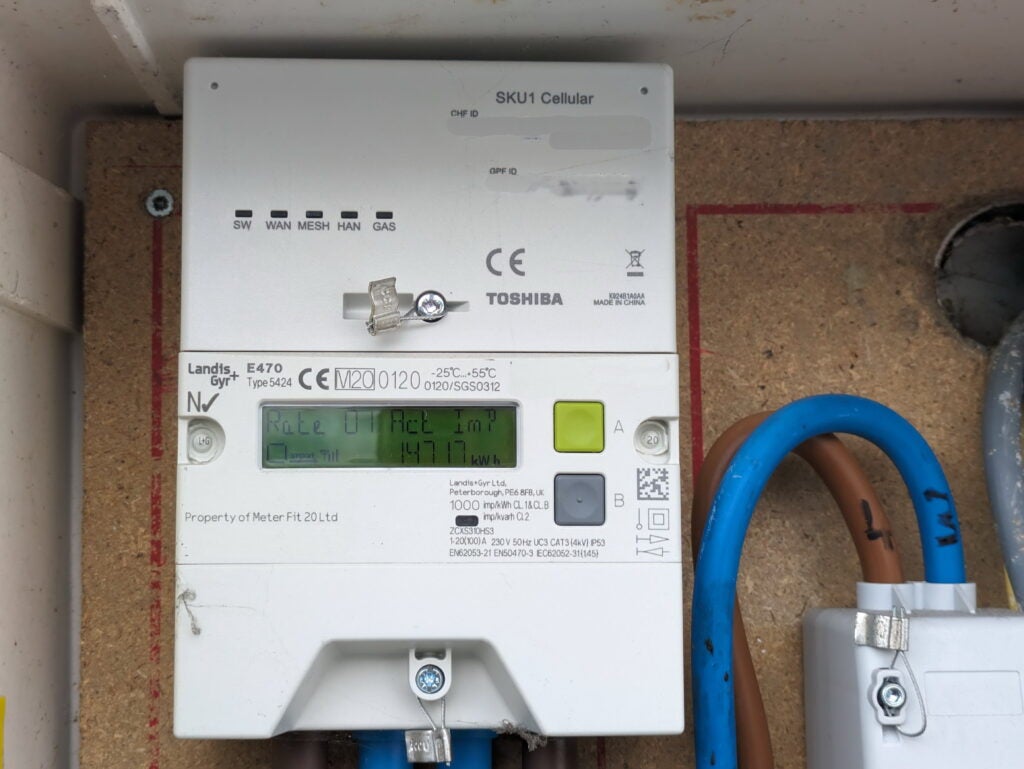

Smart meters are little different from the digital meters they replace.

They measure and display the amount of gas or electricity you’ve used in the same way, but they also record when you used the power. Most importantly, they’re connected to a cellular modem, through which they report data back to your energy supplier.

A smart meter always comes with an in-home display (IHD) unit. These are typically a small colour display that can show how much power you’re using, or how much you’ve used over the past week, month or year. These link wirelessly to the meter and usually have a battery, so you can carry them around the home and see how the power you use varies depending on what you switch on or off.

In fact, there are two types of smart meter in the UK. Consumers that upgraded before 2019 will have a first-generation, SMETS1 meter, while those upgrading now will typically get a SMETS2 device. Almost unbelievably, SMETS1 meters aren’t always cross-compatible between energy suppliers, so consumers who switched supplier after having one installed sometimes lose their smart functions. This issue is now being addressed with an ongoing upgrade programme.

What are the benefits of a smart meter?

Smart meters have plenty of benefits, both for energy suppliers and consumers. They mean neither suppliers nor householders need to bother with regular meter readings, as usage information is automatically sent to the supplier. In turn, this does away with inaccurate estimated readings, and ensures that if the price changes, the supplier knows exactly how much power to charge at the old and new rates.

For many consumers, a smart meter’s IHD can be very useful. Knowing how much power you’ve used in a week, month or year can really help you budget. Additionally, seeing how much electricity you’re using at a given moment can be an excellent way to zero in on power-hungry appliances or wasteful habits, and give you a great sense of what really uses the electricity in your home.

But for consumers, the real benefits of smart metering are likely to come from the flexible and competitive tariffs that they make possible.

The UK has had Economy 7 and other dual-rate tariffs since 1978. Before smart metering these needed a special dual meter which logged daytime and cheap rate use separately.

New smart meters support a much wider range of off-peak and variable rate tariffs, which can potentially save users a fortune. As an example, many electricity suppliers now offer off-peak and electric vehicle (EV) tariffs, with perhaps four, six or eight hours of discounted electricity overnight.

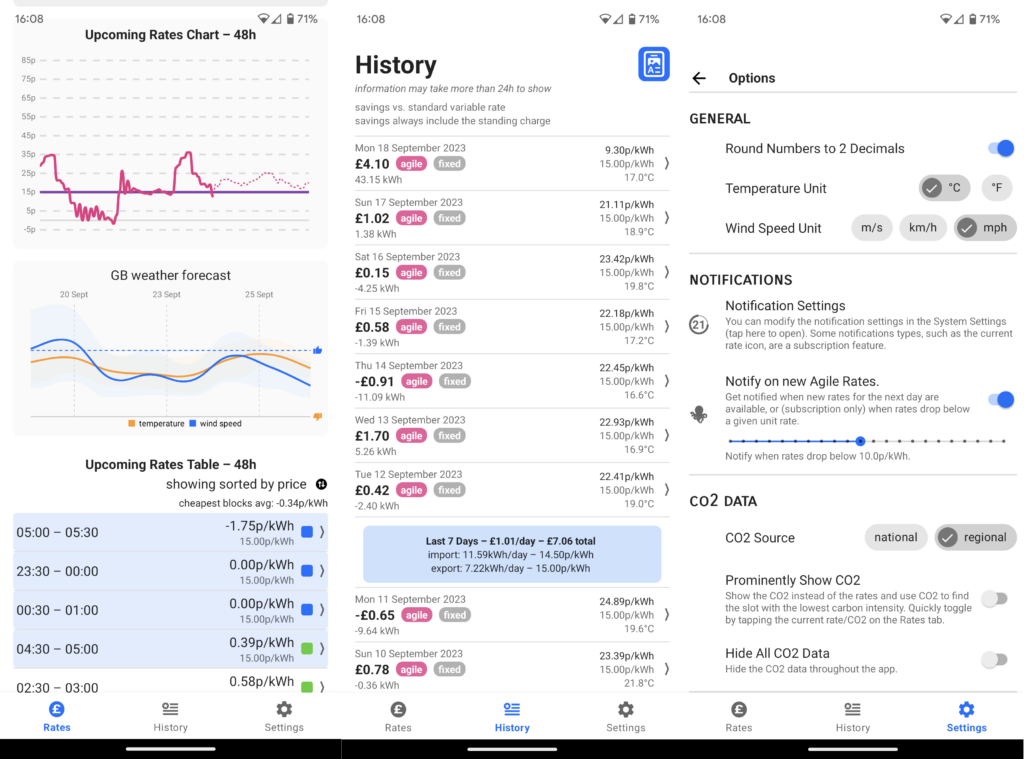

With smart metering, these are becoming increasingly flexible and sophisticated. So-called ‘time-of-use’ tariffs like Octopus Energy’s Agile Octopus even offer a flexible rate that changes half-hourly based on that day’s wholesale electricity price. During periods when demand is low and supply plentiful, this price can turn negative, meaning that you’re occasionally being paid to take electricity from the grid.

More typically, such flexible tariffs offer moderate savings to people who can shift their electricity use away from the evening peak. By charging cars, and running dishwashers and other appliances when demand and prices are low, these users pay less, and reduce the overall demand at peak times – lowering the UK’s reliance on more polluting energy sources.

This is a similar goal to the National Grid’s Demand Flexibility Service, which uses incentive payments to reward customers who can cut down on their peak time electricity use. Several energy suppliers and thousands of customers took part in several trials during winter 2022-23, and the service will continue in winter 2023-24. However, as the trials are targeted at short periods on specific days, they’re only available to users with a smart meter.

One final benefit of smart meters is that they’re bi-directional. In other words, they can measure any power you export back to the grid – for example from solar panels or a battery storage system. Again, this does away with the need for export meter readings, and it opens up support for variable rates. As an example, Octopus also offers a variable export tariff with half-hourly pricing.

If you’ve got a smart meter, time-of-use tariffs and a large battery, you could make money by storing electricity when it’s cheap and selling it back to the grid when demand is high. It might feel like a scam, but in fact you’re helping balance the UK’s evolving power grid. With help from the large batteries in EVs, this is likely to become quite widespread in the future.

What are smart meters like to use?

Smart meters are easier to use than conventional ones. You don’t need to take meter readings, but you still can should you need to – either from the meter itself, or from the IHD. It’s still a good idea to do this whenever you switch suppliers.

You don’t need to do anything else with a smart meter, which just works in the background, but you’ll get the most from one if you use the IHD to at least keep track on your spending. IHDs are essentially portable displays, usually with a touchscreen. It’s easy to change between their main information screens, although accessing and configuring advanced functions – like setting a daily budget – can be a pain.

What are the downsides of a smart meter?

We’ve established that there are loads of good things about smart metering, but there are some downsides. Chief among these is that energy suppliers can change the mode of a smart meter without needing to visit your home. If you owe money for your bills, your supplier could remotely switch your meter to prepayment mode, which requires upfront payment and typically costs more.

In February 2023, in response to a growing number of forced metering changes, Ofgem asked all energy suppliers to pause this practice until they had agreed a new set of guidelines. If and when it resumes, some customers can refuse to be moved to prepayment, as detailed in this Citizens’ Advice article.

A smart meter can also be used to disconnect a consumer remotely. However, energy suppliers aren’t allowed to disconnect homes unless they’ve first contacted you to discuss repayments, and visited your home to assess whether disconnection would affect your personal situation.

Some users are concerned about the data gathered by a smart meter and shared with the energy supplier. It’s an understandable concern, but meters can only report how much gas or electricity your home uses, and when. According to Smart Energy GB, the body tasked with promoting the smart metering rollout, smart meter data is encrypted and shared only with your energy supplier. Some anonymised energy-use data is also shared with energy network operators – the companies that manage local energy infrastructure.

It’s conceivable that, should your smart meter data be intercepted, half-hourly energy use information might be enough to reveal more about your household – for example, including when you sleep or when your home is empty. Users can lower this risk by opting out of half-hourly data and just sending daily updates, but this could prevent you realising many smart metering benefits.

A final, potential concern about smart metering is that it might ultimately allow energy companies to force customers onto time-of-use tariffs. For me, these are great: I mostly work from home, so I’m here to charge my EV, run appliances and do other energy-intensive things whenever electricity is cheap. They don’t suit everyone, though. If you’re out all day, then cook dinner and run appliances at peak times, you’re likely to pay significantly more.

As yet there are no plans to force customers onto variable or time-of-use tariffs, but these do feature heavily in governments’ strategies to manage energy consumption and maximise the use of renewable power. As it stands, they’re a money saver for those who can be flexible, rather than a way to penalise those who can’t.

In practice

There can be other practical drawbacks and limitations to smart meters. It typically takes 2-4 hours to install smart electricity and gas meters, and you may be disconnected for much of this time. Smart meters require a 3G mobile data signal, so they can’t be installed in all areas. Also, as I mentioned, SMETS1 meters that haven’t yet been updated can’t always be switched between suppliers without losing their smart features.

There’s certainly plenty of room to improve the smart meter user experience. My IHD – a widely used Chameleon model – can show how much electricity we’re exporting at a given moment, but it doesn’t show the export total for a day, week, month or year as it does for our consumption. More significantly, it’s ignorant of the half-hourly tariff we’re signed up to, so its cost calculations are completely wrong. We get much more useful historical information from our energy provider’s app.

I discovered by accident that there’s a byzantine complexity to the system on which smart meters run. Ours was originally installed by Bulb, who didn’t add it to the relevant database, so when we switched to Octopus it took weeks before the company could establish communication and get any readings. I was told there could be up to 14 different parties involved in smart meter provisioning. We also had problems getting our power export set up – although it uses the same meter, you need a second meter number, and our network operator seemingly didn’t add this to the right database, either.

To be fair, the energy suppliers themselves know that the system is imperfect. For example, Octopus CEO Greg Jackson has addressed it in more than one blog post.

Final thoughts

Smart meters definitely have their flaws, and their rollout hasn’t gone smoothly, but they are an essential component in modernising the UK power network. The industry says they’re secure, and that your data is protected and only shared with your energy supplier. Meanwhile, rules enforced by Ofgem should offer protection from forced metering changes and disconnections.

Set privacy and billing concerns aside, and the choice over whether to have a smart meter is actually quite simple. If you can be flexible with the time of day that you use electricity, you’ll generally benefit from the dual rate or time-of-use tariffs that smart meters support. This is especially the case if you’re a heavy user, for example if you’ve got an electric car or a large family. It’s also especially true if you generate or store electricity that you want to export into the grid – in this case a smart meter is probably essential to getting the best price.

There’s much less incentive to get a smart meter if you’re a light electricity user, and especially if you’ve no choice but to use power at peak times. You’re less likely to save money with a time-of-use tariff, and unless you have electric heating or an electric vehicle you probably won’t benefit significantly from cheap overnight rates. In these cases, getting a smart meter won’t commit you to getting a smart tariff, and it will free you from the hassle of meter readings. However, if you don’t want the upgrade, you’re unlikely to be missing out on smart metering’s other benefits.