The offices of TBWAChiatDay in Los Angeles, built 1996–1998.

Photo: Iwan Baan

In olden days, offices grew as the world shrank. Sunset-free empires and vast trade networks released oceans of paperwork that in turn created a demand for record-keepers, copy-makers, storage systems, evolving technologies of communication, and the real estate to accommodate them all. Offices became the material manifestation of trust. If you knew that a man in a dark suit, sitting in a big stone building at a reputable address in London, had signed a particular document, it endowed that piece of paper with weight and reliability, even in New York or Kathmandu. Great distances also necessitated proximity. Serried rows of clerical workers, insurance adjusters, and financial analysts churned out figures that affected lives and fortunes in far-flung time zones. Five afternoons a week, those white-collar forces scattered, repopulating neighborhoods and suburbs that spread out from office-tower canyons. This weekday web, laced together by telephone, ticker tape, elevator, subway, and commuter train, made the modern city make sense.

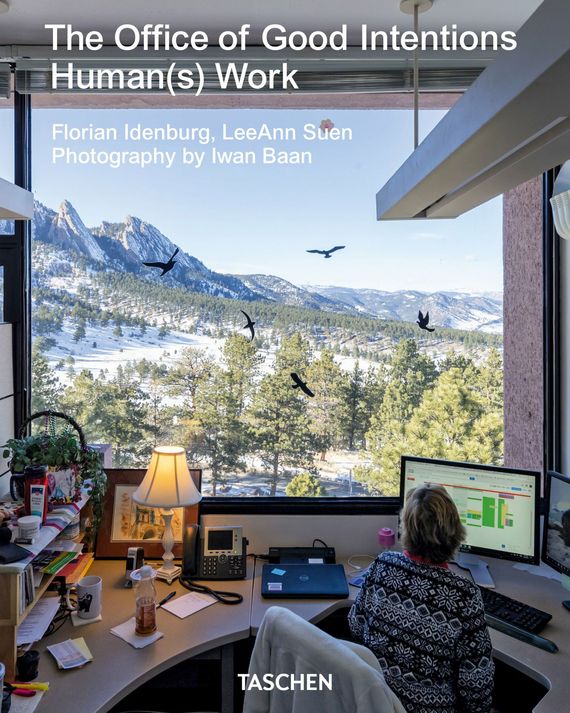

That entire set of interlinked physical structures is a relic now, and not just because of the pandemic. A strange and alluring book, The Office of Good Intentions: Human(s) Work, by the architects Florian Idenburg and LeeAnn Suen, chronicles many attempts to adapt the old analog scheme for the digital age, with results that have ranged from the whimsical to the utopian to the sinister. The collection of essays and case studies doesn’t make an explicit case for or against the office, or offer platitudinous architectural solutions (more lounges, more outdoor space). Instead, the authors roll out a brutal analysis of an entire category of potential clients. With each technological shift, they suggest, companies have tended to treat employees like lab mice, doling out treats, monitoring their behavior, and creating ever more elaborate illusions of freedom. In this scheme, the employee doubles as a product, a font of data that can be packaged for other companies to exploit.

Although the authors don’t quite come out and say this, employers who talk of breaking paradigms also sucker architects into believing that they are shaping new forms of pleasantness, places in which employees can breathe deeply, bask in daylight at a constant 68 degrees, socialize casually, and nourish themselves wholesomely. They design spaces engineered to comfort the body, stimulate the brain, and facilitate collaboration — only to find that they have handed domineering employers insidious new tools of social control. In this jaundiced view, the goal of architecture is to disguise, not reveal, the structure of our days. Long hours of sitting masquerade as wellness, insecurity is palliated by snacks, and flexibility’s just another name for no time of your own.

The foundational story of this dark view is the description of the ChiatDay advertising-firm headquarters in Venice, California, an early-1990s hellhole of inflexibly enforced flexibility lurking behind the binocular-shaped portal designed by Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen. Frank Gehry’s plywood-and-cardboard aesthetic provided the décor for an environment determined by edict: Grab a laptop and find a seat wherever, so long as it’s not the same place you worked yesterday. Nomadism was mandatory, colonizing your own corner verboten. It didn’t last long, but there have been innumerable versions of the same experiment.

Photo: Courtesy of TASCHEN

The authors present that environment as the precursor of the gig economy, which not only eliminated traditional workplace concepts like stability, advancement, and loyalty, but also fostered a culture of fragmentation and distraction. “Today’s worker is encircled by swarms of [apps], each uttering conflicting orders. Taylorism on algorithmic steroids has broken work rhythms into a pandemonium of fractured schedules, collapsed into just-too-late economics. The splintering of space and workers follows suit.”

This doesn’t apply to me, I told myself. I’m just a writer. And then I counted up the number of apps I use to communicate with editors, learn about packages mailed to the office, write and edit text, book work trips, file expenses, transfer and collect large electronic documents, handle photos, view videos, listen to music, schedule meetings, and explore archives: about 25 different pieces of software I use more or less constantly, all of them recording my sedentary activities in minute and highly specific — and therefore marketable — slivers.

The book traces the evolution of algorithms that subject employees to the same real-time data-collection and performance-management systems that govern utilities and security. The badges that employees use to unlock bathroom doors, summon elevators, and pay for lunch have turned humans into components in a system of sensors and tracking devices. The more you know, the more you control. The great 2006 movie The Lives of Others depicted life under constant surveillance: A Stasi officer in Cold War East Germany listens in on a dissident writer’s home life and finds himself falling for the family he is supposed to be victimizing. At the time, it seemed like a horror story; now it reads almost like a fairy tale, enough to make you nostalgic for a time when Big Brother was human.

Idenburg and Suen, their prose fleshed out by dozens of photographs by Iwan Baan, careen through a dizzying assortment of situations: the pajama-clad guru Hugh Hefner fashioning the Playboy aesthetic from his circular command-post bed; unseen cleaners agitating for more humane conditions in L.A.; server farms humming in the desert; suburban office parks; the job-networking extravaganza that is Burning Man; Andy Warhol’s Factory; research labs trying to emulate the inspiration-friendly conditions of Archimedes’ bathtub; dog-friendly cubicle grids; high-tech towers; purportedly ergonomic furniture designed for the nonexistent average body.

Employers have been reinventing the office on a regular basis for at least 30 years, steadily dismantling the appearance of regimentation while camouflaging the pursuit of efficiency in ever more genial costume. The book tells a story of centralized oversight over segmented lives, carried out not by some Dr. No type in a high-back executive chair but by an impersonal, intangible power that runs on plenty of electricity. And because it can exist anywhere, like the Holy Spirit, workers bring it home with them, or take it on the road. The work-from-home revolution turns the bedroom into just one more branch of the data pipeline.

“Woken by a stern but servile, automated, female voice, we start playboring in bed, hop on a hangout during a shared ride to spin class, check our biometrics at the Soylent bar, meet for kombucha, take a shareable cooking class that doubles as lunch, put in two hours of pow-wows at a work-club, another deep-dive, and then … #selfietime! Cities dissolve into a smorgasbord of occupational touchdown offerings for this new world of pseudo-work.”

What do you mean we? I perform exactly none of the trendily self-improving tasks on that list, and I wonder whether work, for most people, really has so thoroughly transformed. I suspect that most “digital native” office workers spend their days similarly to the ways their analog-born parents did: sitting in one place all day long, performing somewhat repetitive tasks that are still resistant to automation. And that’s not even accounting for the untold millions who devote their working hours to filling boxes for delivery, making hotel room beds, or cleaning up errant body fluids.

Still, this book suggests that architects have an ever-more-minimal role in how and where people work. Some keep designing fancy high-rise office buildings or converting old ones to the sorts of places where people can sleep, eat, labor, and commune without ever fully separating one activity from the others. Mostly, professional designers stand by as people cobble together their own workplace bivouacs out of whatever scraps of square footage they can muster. In a sense, this means we have come half circle, partway to the days when most commutes consisted of a stroll downstairs or at most a few blocks. Today we don’t live above the shop; we are the shop.

The Salk Institute research labs in La Jolla, built 1959–1965.

Photo: Iwan Baan

Idenburg and Suen stop short of following their own logic to the urban scale. The fulfillment of this long-term trend of fragmentation and decentralization would reshape cities even more radically than it has so far. Beyond all the kombucha-bar email sessions and rolling Uber meetings, cities will have to once again figure out what they’re for. Perhaps businesses fighting a rear-guard action will rediscover daytime density, measure the value of physical proximity, preserve the intangibles of office culture, and once again promote looking one another in the eye. In the meantime, metropolitan centers need to plan for the opposite outcome: nebulae of semi-self-sufficient neighborhoods and 15-minute cities joined by transit that fewer people take in more and different directions. Slouching from a late-19th-century commuting paradigm into a go-where-you-wish future might ultimately result in a better city and richer lives, but getting there will be almost as traumatic as it was to shift the archetypal urban workplace from the factory floor to the trading floor.