Summary

- Famicom’s colorful design was inspired by Nintendo’s Game & Watch handhelds and was meant to appeal to players of all ages.

- The Famicom features a top-loading cartridge slot, while the NES used a front-loading mechanism with serious design flaws.

- The Famicom features better audio quality and proper save functions thanks to the Japan-exclusive Famicom Disk System.

Before the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) changed the gaming industry forever, it launched a few years earlier in Japan as the Family Computer—also known as the “Famicom.” The Famicom was more than just a Japanese version of the NES, and its differences make it one of Nintendo’s most fascinating systems.

The differences between the Famicom and NES begin with their outer design. In stark contrast to the NES’s monotone gray and white shell, the Famicom console and controllers boast a colorful red, tan, and gold palette. There are a few other visible distinctions between the Famicom and the NES, but we’ll touch on those later.

Besides giving the Famicom an eye-catching appearance, the red and gold casing is also derived from Nintendo’s Game & Watch handhelds. Game & Watch technically wasn’t Nintendo’s first foray into game development—that distinction belongs to the 1977 Color TV-Game 6.

However, the unexpected success of the simple Game & Watch handhelds quickly transformed Nintendo into one of the biggest companies in the gaming industry. The Game & Watch handhelds came in a few different color schemes, but the red and gold palette that inspired the Famicom first debuted with the release of Manhole in 1981.

Nintendo also intended to contrast the bulky and mechanical designs of its competitors by intentionally making the Famicom look like a toy. As its name suggests, the Family Computer was meant to be enjoyed by families and players of all ages, so its small, colorful design helped it appeal to children and adults alike. The console even includes a pointless “eject” button that was solely included to make swapping cartridges seem more fun to kids.

The NES kept the same control scheme, but overhauled just about every other part of the Famicom’s design. Western markets were still dealing with the aftermath of the video game crash of 1983. The industry-wide recession had been caused by the oversaturation of low-quality console games and resulted in the rapid decline of both sales and general consumer interest in new video game consoles. To work around this growing stigma, Nintendo designed the NES to not look like a gaming console and avoided making any connections to video games by promoting it as an “Entertainment System.”

The NES was also designed to be inexpensive, as Nintendo hoped a low price point would entice consumers amid the declining interest in gaming consoles. Its colorless box shape was the result of an attempt to simplify the Famicom’s outer design and reduce costs, but it also led to the removal of some of the Japanese console’s most notable features.

The Famicom’s controllers differ from their NES counterparts in a few other ways, with the most notable being that they are hard-wired into the console. This design choice was meant to contribute to the Famicom’s toy-like design (as well as being cheaper to produce), but it also meant that there was no way to detach or replace the controllers if they broke. The NES addressed this issue by redesigning its controllers to be detachable, as well as being slightly larger to accommodate older players.

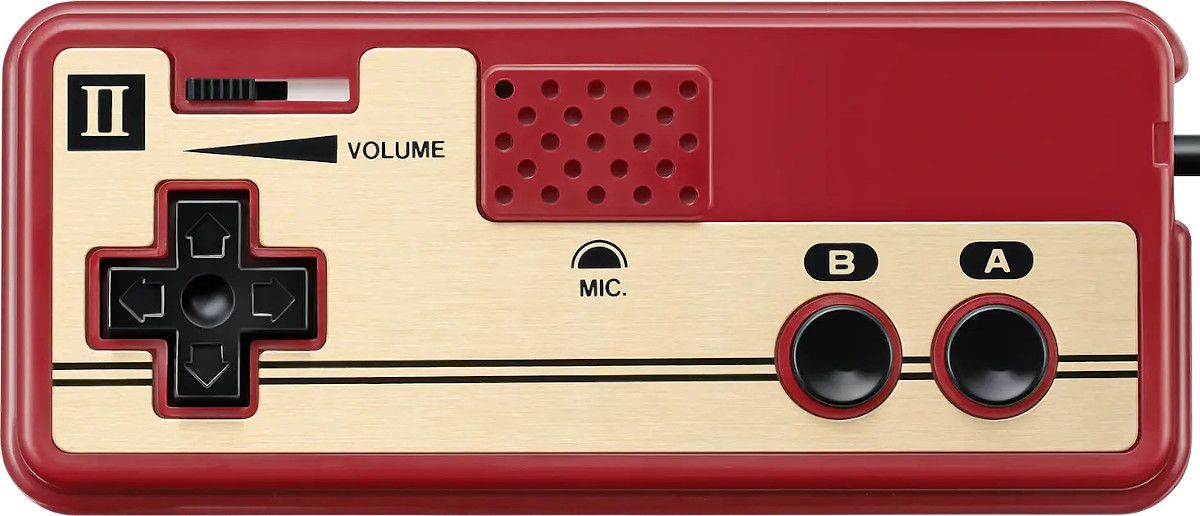

Apart from the obvious shortcomings of hardwired controllers, there is one other feature that sets the Famicom controllers apart from the NES. The Famicom’s Controller II—which is usually reserved for a second player—contains a built-in microphone. Although this feature was hardly used, the fact that the Famicom included voice controls at all was revolutionary for its time.

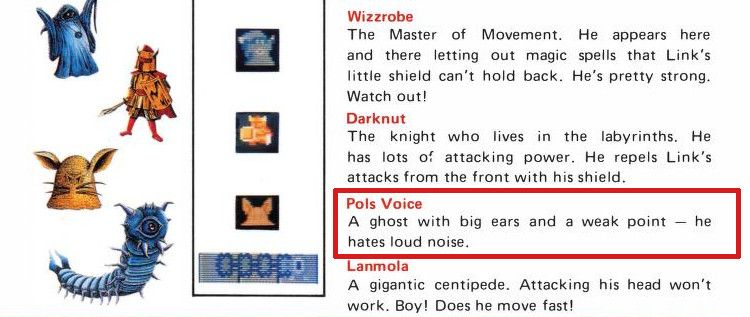

For the few Famicom games that did use the Controller II microphone, it was often reserved for easter eggs or optional commands. The Legend of Zelda allows you to stun Polls Voices—a rat-like ghost found in dungeons—by yelling into the microphone. The NES version removed this feature, though its instruction manual still mistakenly references its weakness to loud noises.

One of the only games to require the microphone is the notoriously terrible cult-classic Takeshi’s Challenge. Multiple sections throughout the game require you to say specific phrases, blow into the microphone, or sing full karaoke songs. Although the game does a poor job of informing you when to use the microphone, the creative use of voice controls in games like Takeshi’s Challenge was ahead of its time.

Possibly the most significant difference between the NES and Famicom is their means of holding game cartridges. The Famicom uses a top-loading mechanism—meaning cartridges are loaded into a slot located at the top of the console—similar to most other cartridge-based consoles. However, as part of Nintendo of America’s plan to pretend the NES wasn’t a gaming console, the NES used a front-loading cartridge slot similar to the ones found in VCR players and videocassette recorders.

Famicom games came in a variety of colorful designs, and their small size made them easy to store away. Nintendo also wasn’t as restrictive on third-party Famicom developers, as some of the console’s officially licensed games use custom-made outer shells and cartridge boards.

Meanwhile, NES cartridges required an entirely different shape and design to fit into the console’s front-loading cartridge slot. NES cartridges are nearly twice as large as Famicom games, and apart from notable exceptions like the golden Nintendo World Championships cartridge, almost all official releases use the same gray cartridge design.

Unfortunately, the NES’s front-loader introduced a massive design flaw. Games placed into the NES’s front-loading cartridge slot tend to bend the connector pins that allow the console to read cartridges. With long-term usage, the connector pins can eventually wear out or become permanently bent out of position. Although these pins can be refurbished, the front-loader’s problematic design means that even replacement parts will be susceptible to the same issue.

Nintendo abandoned the front-loader design for all of its future cartridge-based consoles. In 1993, Nintendo released a top-loader version of the NES that partially resembled the Famicom’s design. Unlike the front-loader model, the top-loader NES does not support composite video, though this feature was also absent from the original Famicom.

Later cartridge-based systems such as the Super Nintendo Entertainment System and the Nintendo 64 were nearly identical to their Japanese counterparts, including their usage of top-loaded cartridges. Even Nintendo’s handhelds and the Switch have followed the Famicom’s top-loaded format.

The NES is home to hundreds of iconic video game soundtracks, but many beloved songs sound completely different on the Famicom. Although both consoles feature similar audio processors and their games use the same musical compositions, the Famicom could deliver higher-quality audio with the help of two Japan-exclusive features.

Unlike the NES, the Famicom wasn’t limited to cartridge-based games. In 1986, Nintendo released the Famicom Computer Disk System—also known as the FDS—which was an add-on peripheral that enabled the console to run games from floppy disks. Games released for the FDS supported a variety of features that weren’t commonly available in cartridge games, with the most important being the ability to save data.

Instead of needing to write down lengthy passwords or beat the game in one sitting, the FDS versions of games like Metroid and Castlevania featured a proper save function with multiple save slots. Later NES and Famicom cartridges for larger games like The Legend of Zelda and Final Fantasy contained a battery-powered RAM that allowed for the inclusion of similar save functions.

Save systems weren’t the only thing the FDS contributed to the Famicom. The FDS also added an extra audio channel to the Famicom, allowing its disk-based games to deliver music with better quality and a wider variety of unique sounds. Compared to their NES versions, the FDS soundtracks are far better at replicating the sounds of traditional instruments and delivering energetic tunes. Even the beloved NES soundtracks of The Legend of Zelda and Kid Icarus can seem like a downgrade after listening to their FDS versions.

Certain Famicom games deliver similarly high-quality music and sound effects with built-in expansion audio chips, which create an additional audio channel from within the game cartridge. Unlike the FDS, which only added one extra audio channel, expansion audio chips could supply multiple additional audio channels. Most of these chips provide three audio channels, though some are capable of using up to 8 extra channels.

As with the FDS, cartridges with expansion audio chips were only released in Japan. The two connector pins that the Famicom used to support expansion audio chips were omitted from the NES. Because of this, NES games didn’t have any means of using additional audio channels, resulting in a noticeable difference between the quality of NES and Famicom music.

That doesn’t necessarily mean the Famicom versions were always better. Musical tastes are obviously subjective, but as someone who grew up with the NES versions of these games, I personally prefer the NES’s soundtracks over their Famicom versions. The NES’s limited audio gives its music a retro charm that’s sorely missing from the FDS and expansion audio chip releases. The one exception is Castlevania III—its fantastic Famicom soundtrack is easily one of the best on either console.

Which is the Better Console?

This will probably sound like a cop-out, but there’s no definitive winner between the Famicom and NES. The Famicom is a more feature-rich system with better audio and long-term durability, but many of these features were severely underutilized. Even the expansion audio chips were rarely used outside a small selection of games.

Although the NES could be seen as a stripped-down Famicom with a tragic design flaw, it also improved upon its predecessor in some ways. The NES’s larger plug-in controllers and composite video support addressed the Famicom’s most obvious shortcomings. That, and it had the power glove.

Your console preference will ultimately come down to your own personal taste. Do you care more about music or graphics? Controller gimmicks or controller comfort? A colorful design that pays homage to retro classics, or a modern look that redefined the future of gaming? Regardless of your choice, it’s easy to understand why both systems are still fondly remembered today.