One of the most frustrating aspects of a career in clinical psychology, says Dr. Nick Taylor, is that the doctor never gets to see the patient at the optimal moment. It is either too early to diagnose the problem, or too late to prevent it taking hold.

In his years working as a clinician with the UK National Health Service (NHS), he says he never met anyone early enough in their journey towards mental illness, which meant people couldn’t receive the right care at the right time.

Taylor attributes this problem to the emphasis placed on reactive healthcare, whereby issues are addressed only after they appear. Instead, he proposes a shift in the approach to dealing with mental ill-health, towards a system built around prevention rather than cure.

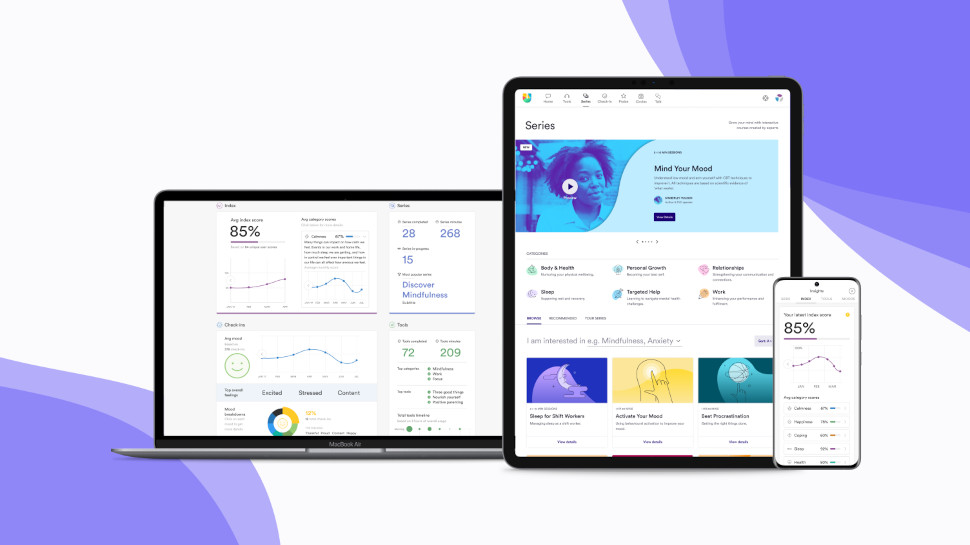

This is the objective of SaaS company Unmind, which Taylor co-founded in 2015. The workplace mental health platform provides employees with a way to monitor fluctuations in their condition, as well as access to meditation exercises and other resources designed to inform a healthier working life.

“We live in a world where we teach our children from age one to brush their teeth, because we know prevention is so important, and the same can be said for physical exercise. That’s exactly where healthcare needs to be,” he told TechRadar Pro.

“The human brain is one of the most complex things in the universe and we don’t get an instruction manual when we receive it. It’s expected that you grow up in life knowing how to manage this thing, but it requires an amount of intentional care.”

In a society in which a quarter of people are said to suffer from mental health problems each year, and there are too few resources to go around, Taylor believes technology can play a key role in helping people manage their own mental health.

A personal connection

Discussions about psychology and mental health have been a fixture in Taylor’s life from very early on. He grew up in a household with three sisters, one of whom has a neurodevelopmental condition called Down Syndrome, which exposed him to a side of life most children are shielded from.

“There was a complexity to Jessica that I didn’t understand at a young age. As I grew up, I formed a deep relationship with her, but a different kind of relationship. Inevitably, it led to me think a lot about the way we build relationships and what they mean,” said Taylor.

“Watching how Jessica was treated by other people and experienced the world around her was informative. It helped me understand that when we are different, we are treated differently, sometimes to the extent that a disability can be compounded by the society around us.”

He says his experience with his sister permeated many aspects of both his and his family’s lives, and instilled in him a deep-rooted curiosity about the workings of the brain.

Although Taylor did not immediately pursue a degree in psychology (his first was actually in music), his interest in the topic remained and he volunteered throughout his studies with emotional support charity Samaritans.

He later took a role at mental health charity Mind as a sleep-in support worker. Taylor’s job was to assist someone with Korsakoff Syndrome, an illness that causes an almost complete loss of short-term memory. Subsequently, he worked in a residential home operated by the charity, supporting people with various other mental illnesses.

Taylor told us it was during this period, under the guidance of the professionals at Mind, that he came to understand how the framework of clinical psychology could be applied to people’s lives to help them both recover and remain well. Eventually, he went on to earn his doctorate in the subject.

Wellbeing in the workplace

One of Taylor’s other “great passions” is working in the garden, and it was while tending to his garden (a fitting metaphor for nurturing one’s mental health, if ever there was one) that his path to founding Unmind first seeded itself.

Although this was before he had retrained as a psychologist, and even before working for Mind, it was at this moment that Taylor realized he wanted to pursue a career in mental support.

Unmind itself was the product of an epiphany, reached separately but synchronously by Taylor and his co-founder Steve Peralta. Both had come to the conclusion that patients rarely receive the right care at the right time, something Taylor had learnt at the NHS and Peralta from his lived experience of mental illness.

The pair agreed that the problem required a new approach based around prevention, and that a digital service embedded in the workplace would provide the ideal vehicle.

As Taylor describes it, Unmind offers customers a platform that “empowers employees to proactively manage their mental health”, through a combination of measurement facilities and access to content (ranging from mindfulness sessions and yoga exercises to healthy recipes) developed by academics and clinicians. The app also signposts users towards services within their organization and in their local area that can help with the onset of mental illness.

The customer, meanwhile, gains access to aggregated and anonymized data drawn down from the platform, which is supposed to inform future HR and mental health strategy. As Taylor points out, mental health issues are currently the single most significant driver of absenteeism, presenteeism and staff turnover, all of which can have a serious impact on productivity and the bottom line.

Unmind has enjoyed a significant period of growth since the transition to remote working, which has emphasized the responsibility of employers where staff wellbeing is concerned. The company also recently raised a $47 million Series B, which Taylor says will go towards expanding the company’s reach and investing in research.

Although attitudes towards mental health have come a long way in the past decade and speaking about mental illness is no longer taboo, Taylor says there is much more work to be done before parity is achieved between the treatment of mental and physical health.

“Overall, the trend is positive and I’m encouraged by the trajectory of the space,” he told us. “But at the same time, it’s important to recognize that the problem is still very common; the prevalence of mental illness in society is staggering.”

“What’s exciting about what we’re doing is that it feels like we’re just at the start of a journey. We’re passionate about our vision of a world where mental health is universally, understood, nurtured and celebrated.”

Measurement paradox

Throughout our discussion, Taylor circled repeatedly back to Unmind’s commitment to the science of mental health, something he is clearly keen to emphasize. Indeed, the company employs a dedicated team of scientists and is participating in a number of studies with the University of Cambridge and University of Sussex.

However, while Unmind is almost certainly capable of helping people improve their awareness of their own mental state, there remain questions over the extent to which it can help fend off mental illness.

The main conundrum is that the company aims to solve a problem before it even exists, which makes empirical measurement of effectiveness almost impossible. Although a customer could feasibly compare data from one year to the next to get a sense of the direction of travel, or use data from a comparable organization as a benchmark, such analyses would lack precision. There is no concrete way to know when you have solved a problem before it becomes one.

Secondly, the platform relies on people’s ability to assess their own mental condition effectively, but it’s difficult to achieve objectivity when performing self-analysis and translating feelings onto a numerical scale is tricky too. The scores allocated to aspects of a person’s mental health by the platform are informed by data provided over time in the form of standardized questionnaires and mood diaries, but the validity of these scores is to some extent linked with that individual’s ability to self-assess.

“Every human being that has ever lived has had mental health from the moment they were born to the moment they died.”

Dr. Nick Taylor

Lastly, there is an opportunity for a misalignment between the objectives of the businesses that recruit Unmind and the end-users of the platform. Naturally, the organization is interested in the benefits from a workforce productivity and strategy optimization perspective, whereas employees are more likely to prioritize their own happiness and wellbeing. Whether it’s possible for the Unmind platform to balance these different and potentially contradictory objectives is unclear.

TechRadar Pro put all of these concerns to Taylor, who pointed out that these kinds of challenges are inherent to the handling of mental health in any context. He also says that giving up all attempts to measure mental health equates to giving up on tackling the obvious challenges it creates.

“There’s the old adage: you can’t manage what you can’t measure,” he noted. “One of the challenges in the field of mental health is that our conscious mind is fickle. Our perception of mental health is really what we’re measuring here, not brain activity or any other physical symptom.”

“But awareness of self is valuable in so many ways when it comes to identifying areas of opportunity. The critical thing about the [Unmind’s] measurement tools is that they correlate with the gold standard measures.”

By this, Taylor means the company’s tests have been designed to map onto standards used in a clinical setting, such as the PHQ-9 assessment for depression and GAD-7 for anxiety. And there is research soon to enter peer review, he says, that suggests digital assessment might actually be the optimal way to triage people suffering from mental illness.

Taylor also contests the idea that the happiness of employees and workforce productivity need be mutually exclusive. In his mind, the former is likely to beget the latter.

A universal problem

The measurement paradox and other questions aside, it’s clear that platforms like Unmind will play a larger and larger role in the workplace in the years to come.

For example, Microsoft recently integrated meditation service Headspace into its collaboration platform, which is used by many millions of workers worldwide. And Taylor says Unmind will pursue similar partnerships in future, provided there is value to the end user.

Although there has been significant progress in attitudes towards mental health, it remains a problem encountered by all businesses and almost all people in some form. This universal quality makes the need for new technology-based approaches all the more urgent, Taylor believes.

“Every human being that has ever lived has had mental health from the moment they were born to the moment they died, and the same will be true of every human being that ever will live,” he said.

“Mental health is a profoundly central part of the human experience, and it’s important we have a toolbox to manage it.”

For all his knowledge and experience, Taylor says he still often fails to practice what he preaches where mental wellbeing is concerned. This he takes as proof that mental health is something that demands continual attention. The sooner that’s understood, the better.