The glossy red cubicles of Garbal’s office in Niamey, Niger’s capital, are tucked away in the second-floor space the call center shares with the local headquarters of Airtel, an Indian telecom. It had only been open for a few weeks when I visited early last year. Bursts of fuchsia bougainvillea garlanded the entryway to the building, a welcome respite from the sand-colored landscape and sewage-infused scent of the rotting industrial district around it. One lot over sat a former Total gas station that has remained unbranded since a drug cartel bought it to launder money and removed the sign. Running across the zone was a boulevard commemorating a 1974 coup d’état, which has been followed by four more over the ensuing five decades, the latest in July 2023. In the middle of the boulevard sat a few dozen miles of decomposing railway tracks that had been “inaugurated” by a right-wing French billionaire in 2016. For decades, postcolonial elites, promising development, have pillaged one of Africa’s poorest countries.

In more recent years, various Western players touting tech trends like artificial intelligence and predictive analysis have swooped in with promises to solve the region’s myriad problems. But Garbal—named after the word for a livestock market in the language of the Fulani, an ethnic group that makes up the majority of the Sahel’s herders—aims to do things differently. Building on an approach pioneered by a 37-year-old American data scientist named Alex Orenstein, Garbal is focused on how humbler technologies might effectively support the 80% of Nigeriens who live off livestock and the land.

“There’s still this idea of ‘How can we use new tech?’ But the tech is already there—we just need to be more intentional in applying it,” Orenstein says, arguing that donor enthusiasm for shiny, complex solutions is often misplaced. “All of our big wins have come from taking some basic-ass shit and making it work.”

HANNAH RAE ARMSTRONG

Garbal’s work comes down to data and, critically, who should have access to it. Recent advances in data collection—both from geosatellites and from herders themselves—have generated an abundance of information on ground cover quantity and quality, water availability, rain forecasts, livestock concentrations, and more. The resulting breakthroughs in forecasting can, in theory, help people anticipate—and protect herds from—droughts and other crises. But Orenstein believes it is not enough to extract data from herders, as has been the focus of numerous efforts over the past decade. It must be distributed to them.

The work couldn’t be more urgent. The region’s herders face an existential crisis that has already started to shred the very fabric of society.

Herding—prestigious, high risk, and one of humanity’s most foundational ways of life—is a pillar of survival in the Sahel. In Niger, for instance, known across the continent for its succulent steak, animal production accounts for 40% of the agricultural GDP. Migratory herders usher between 70% and 90% of the cattle population between seasonal pastures, since they rarely own land. These pastoralists have historically relied on common resources, in coordination with local communities.

But the traditional ways are becoming next to impossible. The crisis stems, in part, from the changing climate: as the desert creeps south, and as the dry season stretches longer and the rains come in shorter and more volatile intervals, water, pasture, and other renewable resources are increasingly erratic. But the strain is also political: brutal fighting between pro-government forces and local groups with links to Boko Haram, Al-Qaeda, and the Islamic State has turned major transit hubs, cow superhighways, and wetlands into battlegrounds. Making matters worse, herders tend to be underrepresented within state institutions, whose land-use policies favor farmers, and overrepresented within jihadist groups, which appeal to this exclusion to draw recruits from herding communities. A common lack of schooling among children of herders further deepens this exclusion.

ALAMY

The result is that tens of millions of Sahelian herders who depend upon free movement are increasingly penned in. Things are especially dire for Fulani herders, who get scapegoated as troublemaking outsiders. So addressing the multidimensional crisis would not only help herders; it could remove an intractable driver of one of Africa’s worst wars.

“Ensuring that herders have land and water rights, and working out their access to these through dialogue, is an important part of the solution to conflict in the Sahel,” says Adam Higazi, a researcher at the University of Amsterdam and Nigeria’s Modibbo Adam University, whose 2018 report on pastoralism and conflict for the UN’s West Africa office remains a key reference in the field.

The question now is whether Garbal and a handful of other tech-driven projects can in fact deliver on promises to help stabilize herders experiencing rising precarity.

Aliou Samba Ba, who leads a regional pastoralist organization that has teamed up with Orenstein to get data to Senegalese herders, says he’s optimistic, largely because Orenstein is turning traditional interventions upside down: “We say he looks with the eye of the herder as well as with the eye of the satellite.”

When institutions fail

The Sahel stretches from Senegal’s Atlantic coastline across Africa to the Red Sea, bounded by the Sahara to the north and by verdant forests and savanna to the south. Much of the region has been ravaged by drought and insurgencies over the past few decades, but rural Senegal is still home to the types of spaces that herders elsewhere are fighting for: maintained, not overdetermined; protected, not overpoliced. There is climate change here, but no war.

Last September, I drove deep into the Ferlo, a pastoral reserve roughly the size of New Jersey, to meet with a Fulani herder named Salif Sow.

It was the height of the rainy season, and the Sahel was having a great one. The environment that greeted me was a miracle and a mirage—a desert burst into bloom. Tall, bony Fulani herders scrambled to keep up with throngs of lambs, goats, cows, and camels spread out over a seemingly infinite expanse of green grass and lushly foliated trees. The Ferlo was brimming with carefully maintained wells, abundantly filled seasonal ponds, and clearly marked pastoralist corridors, with the country’s biggest wholesale livestock market just a few hours’ ride by donkey cart. There were no paved roads, no commercial farmland, and no extremist recruiters for hundreds of miles in any direction.

SVEN TORFINN/PANOS PICTURES/REDUX

Not that the herding was easy work. “A herder’s life is difficult,” Sow said, welcoming me to his compound with sweet tea and a calabash filled with fresh milk. “There is not one day of rest.”

In a few months’ time, the rains would stop, the herds would exhaust the pastures, and the grassland would revert back to desert. And Sow would again face the difficult decision he faces every year: whether to stay and buy livestock feed to tide his animals over until next year’s rains or to lead his cows on a journey, and if so, where.

A lot of complex spatial calculations go into choosing where to take hundreds of hungry cows to wait out the dry season on the edge of the world’s largest subtropical desert, while making sure they have enough to eat along the way. Observing these deliberations filled Orenstein with wonder more than a decade ago, when he started surveying herders in Chad for a food security project with the French NGO Action Against Hunger (ACF).

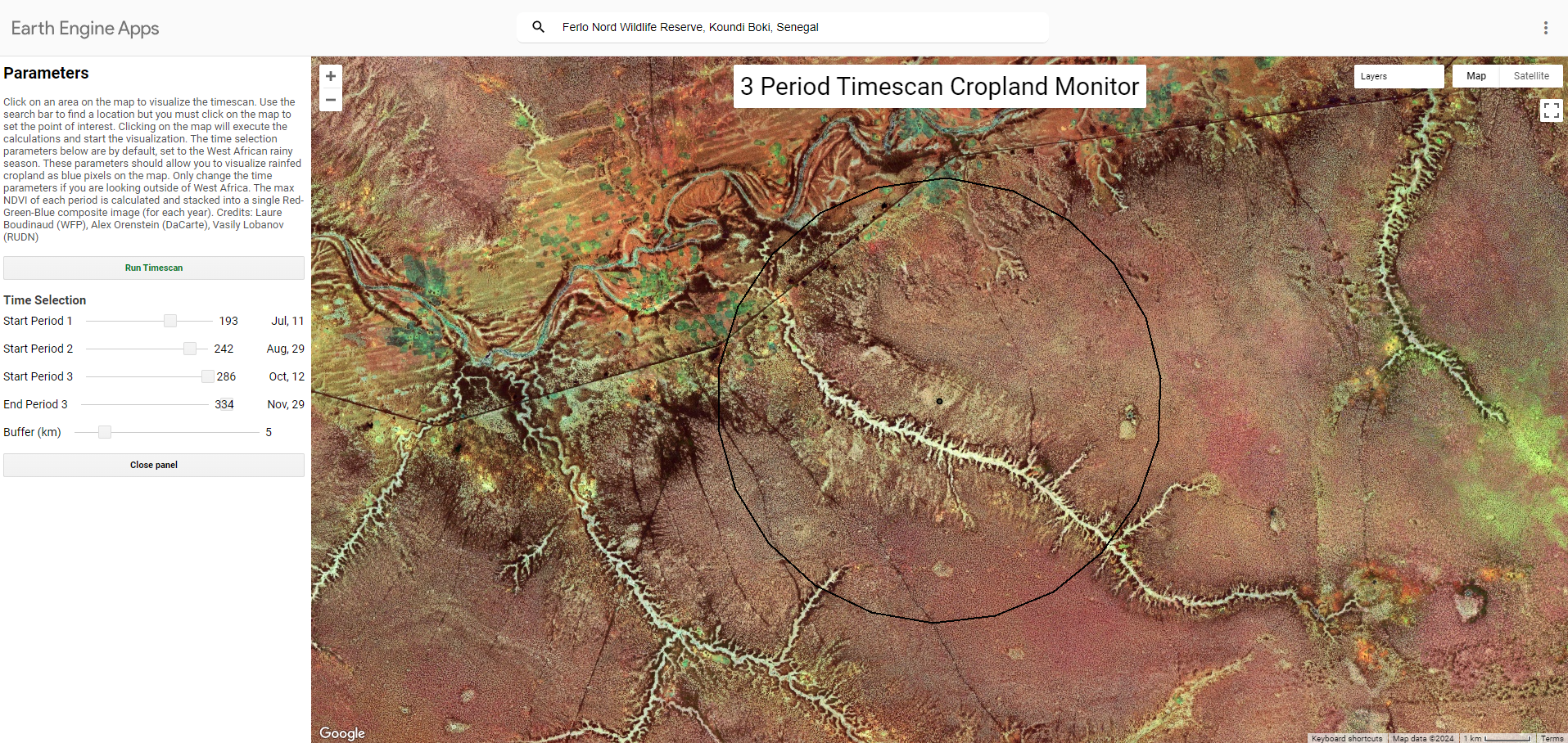

In 2014, Orenstein helped ACF develop an early-warning system, mining new data sources using remote sensing—observing the conditions of grazing pastures from space via satellite imagery and, in some cases, with the use of drones. He also worked with pastoralist organizations to gather information about diverse conditions on the ground, ranging from wildfire locations to the spread of animal disease. He then began making maps using open-access sources; passing the data through an algorithm that he developed to treat and filter imagery, he created detailed and accessible illustrations of rainfall levels and vegetation that became a rare reliable resource for herders and their allies. Aid workers in war zones would print out his maps and pass them around to herders.

It was part of a system designed to extract data, analyze it, and send it up the chain to institutions, including national ministries, UN agencies, and donors. Being able to see crises coming, the thinking went, would give institutional actors more time and power to prepare their response and assign their resources. Being able to deploy emergency programming earlier would in turn afford herders a bit more protection.

In practice, that’s not always how it worked.

At the start of the rainy season in the early summer of 2017, Orenstein was tracking rainfall patterns and felt a knot in his stomach. The first rains had hit too hard, washing the dormant seeds out of the soil; a dry spell followed that lasted for several weeks. When the rains did return, the grassland growth was stunted. Drought was coming.

By mid-August, Orenstein was scribbling reports and ringing journalists to warn that disaster was imminent. But when presented with this evidence, the regional body with the authority to declare an emergency did not act. By the time it finally did, in April 2018—eight months after initial warnings were sounded—it was far too late to respond effectively to what turned out to be the worst drought in 20 years.

COURTESY OF ALEX ORENSTEIN

Two months after that, in June 2018, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs urgently warned that 1.6 million children faced severe acute malnutrition, up more than 50% from the previous year.

That blighted season was also brutal for Sow. In March, his entire village sent its animals south to escape the drought—the first time anyone could remember doing so that early in the dry season. But Sow lingered, unwilling to take his sons out of school to help him. Nonetheless, he also could not afford to stay and buy several tons of animal feed per month at inflated prices. By the time Sow finally hired a few assistants and headed south with his cattle, sands had engulfed the grasslands.

They marched across the desert like soldiers at war, covering 18 miles a day. On the 10th day, they reached the Tambacounda region by the Malian border, where the cows would spend the rest of the lean season grazing on savanna woodlands and lush forest. Not all the herd survived the trek, and the cows that did were emaciated and more prone to insect-borne tropical diseases. By season’s end, a quarter of the herd had dropped dead—a defeat from which Sow still hasn’t recovered.

Democratizing data

Driving through the Ferlo in 2018, Orenstein was distraught to see the rail-thin Fulani herders trailing behind their withering cows. Across the Sahel, anti-Fulani pogroms were on the rise; some West Africans were taking to Twitter to call for their extermination. As weather, food, and protection systems broke down, it was easier to scapegoat the drifting “foreigner” than to demand accountability from anyone responsible.

The combination of starvation and ethnic massacres reminded Orenstein of the stories his grandfather used to tell of surviving Auschwitz. What good were early warnings if institutions were not willing to act on them? Not that the drought could have been prevented. But declaring an emergency sooner would have facilitated measures to soften its impact on herders. For example, governments could have sent cash transfers and distributed food for both humans and livestock at strategic transit locations.

From that point on, Orenstein decided to do things differently. If institutions could not be trusted to make good use of new data, why not get it directly to herders?

But delivering data to herders would prove extremely challenging. The centralized, vertically oriented systems traditionally used for data collection and analysis are better adapted to those institutions, usually located in capital cities, than to herders dispersed across thousands of miles of desert. What’s more, Sahelian herders are some of the world’s least reachable, least connected people. Many of them don’t have cell phones or access to internet or strong cellular service.

Still, the timing was good—aid workers and donors were increasingly hopeful that technology could solve stubborn problems. In 2018, Orenstein secured a $250,000 grant for ACF to broadcast data reports to herders in northern Senegal via text message and community radio.

The project launched several months later, though by then Orenstein was already working on another one: the Garbal call centers. Even more than community radio, the call centers, which are a collaboration with the Netherlands Development Organization, could offer data tailored to individuals in very specific locations over a wider remit. The first center launched in Bamako, Mali, in 2018. Another, in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, followed in 2019.

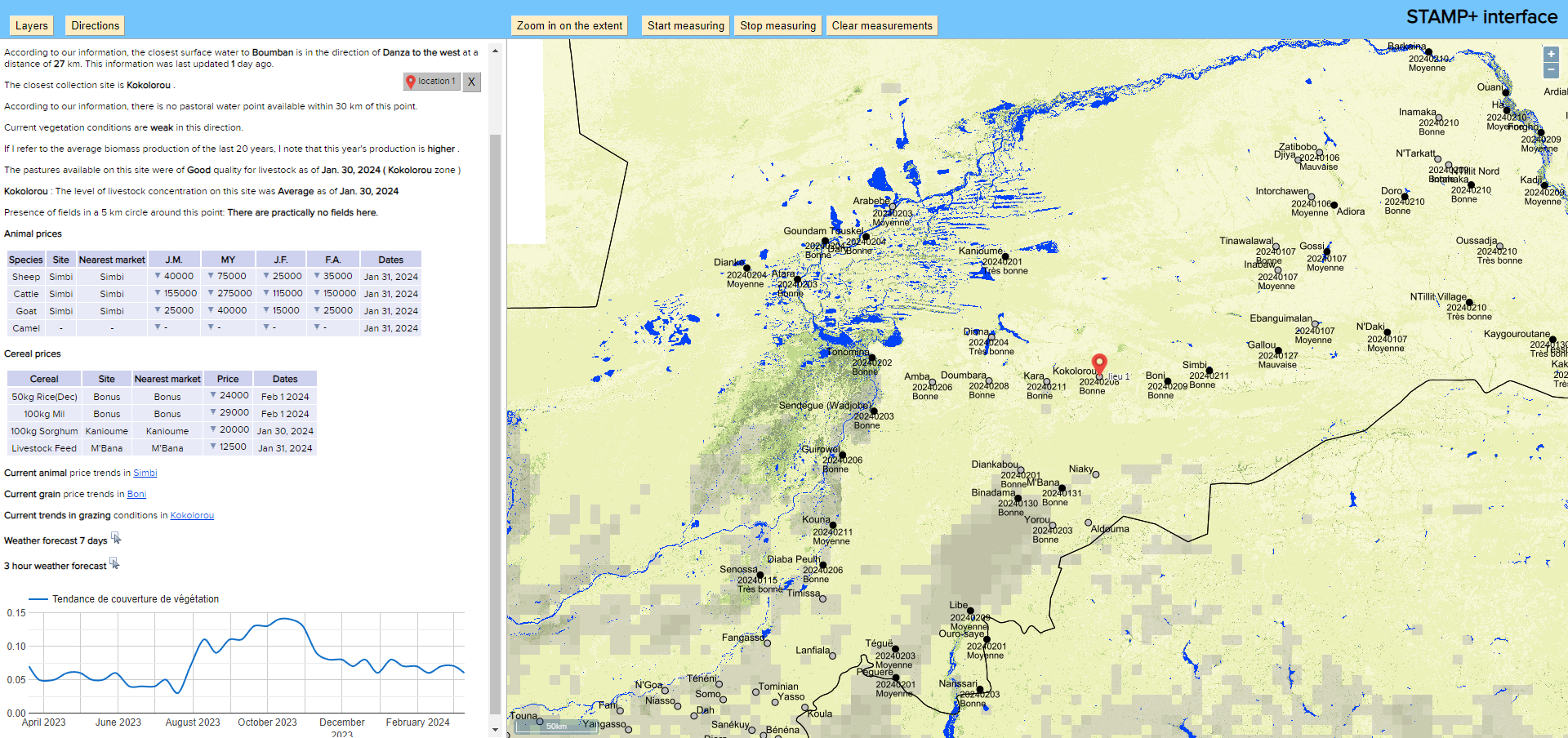

Orenstein and the Garbal team—roughly a dozen local data analysts, project managers, digital finance experts, and tele-agents with degrees in livestock management and applied agriculture—have designed different tools for herders’ needs. For example, they’ve offered ways to connect with veterinarians, compare market prices for animal feed, and use satellite data to find seasonal migration corridors and track brushfires. Crucially, the team has also engaged directly with pastoralist organizations, training and equipping herders to send back field data about vegetation quality in different zones—a piece of critical information that is undetectable via satellite.

Orenstein himself went into the field as often as he could to hold focus groups with herders and ensure that the way information was delivered would be adapted to their epistemic culture. “Instead of asking them, ‘Do you need rainfall information?’ I would say, ‘What kind of information do you need? And how do you measure it?’” he recalls. “Otherwise, the system would tell them to expect 25 millimeters of rain. Math is not how they measure. So instead, I would hold consultations on pond fullness, for example, and define rain strength in those terms—terms they can use.”

Samba Ba, the Senegalese herder, notes how effective this work has been in bridging the gulf between what tech had promised and what he and his peers actually needed. “Orenstein would help us forecast in September what the vegetation would be like the following year, so we could plan the next seasonal migration,” he says. “He came to us in the field, took into account our customs, habits, and knowledge, and used technology to give us a clearer idea of the grazing situation.”

Still, the most popular Garbal service has been its weather forecasting for rural zones. Previously, reliable information was severely lacking, in part because there were not enough ground stations and in part because satellite data was available only for urban areas. (Mali, for instance, has just 13 active weather stations, compared with 200 in Germany—a country one-third its size.)

Orenstein came up with a way to make rural forecasts more readily available. “We had the coordinates for every village in Burkina Faso. Why couldn’t we just plug those into an API?” he remembers thinking, referring to an application programming interface, a kind of intermediary that allows applications to interact with one another. “Suddenly, we were getting weather forecasts for places that weren’t listed anywhere.”

The API has enabled Garbal tele-agents to click on remote pastoral zones on a map and receive tables showing weekly, daily, and hourly forecasts that are updated with fresh satellite data every three hours. Honoré Zidouemba, the project manager for the Ouagadougou call center, estimates that during the rainy season, his center receives 2,000 to 3,000 calls a day about the weather. “Herders and farmers used to derive information from natural cues,” he says, “but with climate change, those are more and more perturbed.”

It’s simple and inexpensive—costing under $100 a month to use—but of all the team’s technological innovations, the API has made the biggest impact. And it’s a far cry from the kinds of higher-tech applications NGOs and development organizations have been promoting.

Since 2015, the World Bank has committed half a billion dollars to a two-phase project to support Sahelian herders’ “resilience” through strategies that include developing technological tools to map pastoral infrastructure. A senior humanitarian-agency staffer working with herders and technology, who requested anonymity to speak frankly, says the resulting databases have not been shared with herders; he calls the approach, which is geared more toward informing institutions than informing herders, “very technocratic.” (The World Bank did not respond to a request for comment.)

Meanwhile, ACF, the French NGO Orenstein previously worked with, got international attention in 2020 for reportedly using AI to help herders, a claim several people involved in the project say was simply incorrect. (“ACF does not use self-learning for its Pastoral Early Warning System. Presently, the analysis is done ‘manually’ by human expertise,” says Erwann Fillol, a data analysis expert at the organization.)

ALAMY

Other groups are experimenting with using predictive analytics to forecast displacements and herders’ movements. A pilot project from the Danish Refugee Council in Burkina Faso, for example, predicts subnational displacement three to four months into the future, allowing aid workers to pre-position relief. “Anticipatory action in response to climate hazards can be more timely, dignified, and cost effective than alternatives,” says Alexander Kjaerum, an expert on data and predictive analytics with the organization. “AI is a last option when other things fail. And then it does add value.”

Still, some argue these kinds of projects have missed the point. “How are high technology and AI going to address land access issues for pastoralists? It is questionable if there are technological fixes to what are political, socioeconomic, and ecological pressures,” says Higazi, the pastoralist expert.

Blama Jalloh, a herder from Burkina Faso who heads the influential regional pastoralist organization Billital Maroobé, echoes this broad sentiment, arguing that big-budget, high-tech efforts mainly just produce studies, not innovation.

Taking matters into its own hands, in 2022 Billital Maroobé organized the first hackathon designed by and for Sahelian herders. Jalloh says the hackathon aimed to narrow the gap between herders and tech developers who lack familiarity with herding lifestyles. It granted up to $8,000 to startups from Mauritania and Mali to track animals and introduce digital ID cards for herders, which could help them cross borders more seamlessly.

An uncertain future

With three call centers now open, and Orenstein serving as a remote technical advisor from the US, the Garbal team is striving to stay focused and make their work sustainable.

Nevertheless, the fate of the project is far beyond its supporters’ control. The region’s slide into violence shows no sign of stopping. As a result, even though more of the herders that Garbal set out to support have started carrying smartphones charged with battery packs, they are increasingly being pushed out of cell range.

AP IMAGES

Between 2018 and 2022, Burkina Faso witnessed one of the world’s fastest-growing displacement crises, with the number of internally displaced people exploding from 50,000 to 1.8 million—almost 10% of the population. Fulanis in particular were targeted for killing by security forces and government-backed vigilantes, and in some areas that are home to significant Fulani herding communities, militants destroyed as many as half the mobile-phone antennas. One tele-agent says the herders who did manage to call in from war zones told her how happy they were to reach the center. When I visited the Ouagadougou call center last year, a tele-agent named Dousso, a 24-year-old with a livestock degree who speaks French, Gourmantche, Dioula, and Moré, told me that “all of the coups,” as well as incidents in which jihadists took over markets, were also making it increasingly difficult to get certain types of data.

This can make the service even more meaningful where it’s still available, says Catherine Le Come, a Garbal cofounder, pointing to Mali, where Garbal is still accessible in some parts of the country that are now cut off from the state.

Yet Garbal, just like other efforts to get data to herders, faces the always pressing issue of how to fund this work consistently over time.

Nonprofit projects like ACF’s community radio and SMS bulletin alerts are pegged to funding cycles that run out after a few years. In March 2021, for instance, as Sow marched his cows 140 miles east toward the Senegal River, he relied on geospatial data he received by community radio and text message from two different NGOs, informing him where pastures were plentiful. But just three months later, both projects ran out of money and stopped supplying information.

THOMAS GRABKA/LAIF/REDUX

The Garbal call centers are trying to build a more sustainable model. The plan is to phase out NGO sponsorship by 2026 and operate as a public-private partnership between the state and telephone operators. Garbal charges callers a modest fee—the equivalent of five cents a minute—and has plans to roll out online marketplaces and financial products to generate revenue.

“Technology in itself has lots of potential,” says Le Come. “But it is the private sector that must believe and invest in innovation. And the risks it faces innovating in a context as fragile as the Sahel must be shared with a public sector that sees user impact.” (Cedric Bernard, a French agro-economist who has worked with ACF, firmly disagrees; he insists that the information should be free, and that trying to be profitable “is going the wrong way.”) Furthermore, the for-profit model means that Garbal—which set out to help vulnerable herders—is already pivoting toward providing services to farmers, who make more reliable customers because they are easier to reach and better connected. Zidouemba, the Ouagadougou project manager, says that its callers are now overwhelmingly farmers; herders, he estimates, account for just 20% of the calls to the Burkina Faso center.

HANNAH RAE ARMSTRONG

As the tides of data that reach them ebb and flow, the herders themselves are aware that the real work needed to keep their way of life going is a longer-term political effort. As I prepared to leave the Ferlo this fall, the landscape still resplendent from the rainy season, Sow pulled me aside. He was a modest man, but there was something he wanted me to know. That very night, he said shyly, his eldest son, Abdoulsalif, was leaving Dakar for Paris to begin graduate studies at the Sorbonne, where he had received a scholarship—a fruit of the sacrifice that Sow made during the year of the terrible drought.

I reached Abdoulsalif over WhatsApp a few weeks later, by which time he had learned that Sciences Po was more prestigious than the Sorbonne and enrolled there instead. He is studying public policy and plans to seek work on pastoralist policy in the Sahel after graduation.

“Herding is a beautiful way of life, a space where I feel very happy,” Abdoulsalif told me. “It is extraordinary to see, so far away, the animals in their vast spaces. Far more beautiful than to live in a place with four walls. Even in Paris, I feel nostalgic for this life, this space of herders.”

Hannah Rae Armstrong is a writer and policy adviser on the Sahel and North Africa. She lives in Dakar, Senegal.