When we think of moons, we usually think of our Moon. It’s bright and familiar, can be seen with the naked eye, and the only one humans have ever set foot on. But in the grand scheme of the solar system, Earth’s Moon isn’t as big as you might think.

10

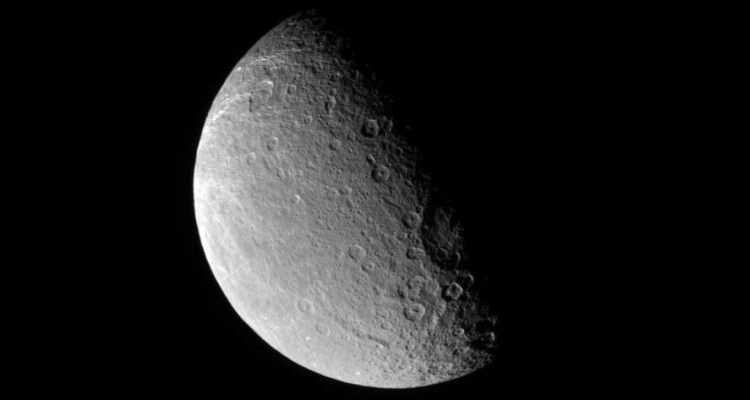

Oberon (Uranus) – 1,523 km

- Diameter: 1,523 km

- Size compared to Earth’s Moon: 43.8%

- Year discovered: 1787

Oberon is Uranus’s second-largest moon, and like most of its neighbors, it’s a cold, cratered chunk of ice and rock. It was discovered in 1787 by William Herschel, the same astronomer who found Uranus.

Its surface is covered in craters, some with bright peaks in the middle, hinting at buried ice. There are also some mysterious dark patches, possibly left over from ancient geological activity. But for the most part, Oberon seems to be a pretty quiet place.

The only close-up photos we have of Oberon came from NASA’s Voyager 2 flyby in 1986. Since then, it’s been largely ignored, but it’s still an interesting moon. Like many of Uranus’s moons, it’s named after a Shakespearean character. In this case, the king of the fairies from A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

9

Rhea (Saturn) – 1,529 km

- Diameter: 1,529 km

- Size compared to Earth’s Moon: 44%

- Year discovered: 1672

Rhea is Saturn’s second-largest moon, discovered way back in 1672 by astronomer Giovanni Cassini. It’s mostly made of ice and rock and, like a lot of Saturn’s moons, it’s covered in craters. Some of these craters have bright streaks running through them, possibly from ice exposed by past impacts.

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft took a closer look at Rhea and confirmed that it doesn’t have much of an atmosphere, though there’s a chance it could have a thin layer of oxygen or even a hidden ocean beneath its surface.

One of the more interesting (and weird) discoveries was the possibility of a ring system around Rhea. If true, it would be the only moon we know of with its own rings.

8

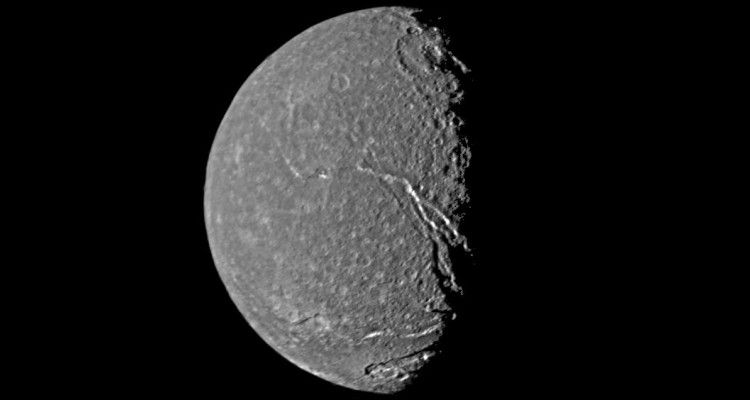

Titania (Uranus) – 1,578 km

- Diameter: 1,578 km

- Size compared to Earth’s Moon: 45.4%

- Year discovered: 1787

Titania is the biggest moon of Uranus, discovered by William Herschel in 1787. It’s a frozen world covered in craters, canyons, and long cracks, which suggests that at some point the surface shifted and reshaped itself.

Voyager 2 gave us the only close-up images of Titania when it flew past Uranus in 1986. The pictures showed many geological features, hinting that the moon may have been more active in the past. Some scientists think there could even be a hidden ocean beneath the ice, though there’s no proof yet.

Since we haven’t sent any spacecraft back to Uranus since Voyager 2, Titania remains a bit of a mystery. It’s definitely on the list of places scientists would love to explore if a mission to Uranus ever gets the green light.

7

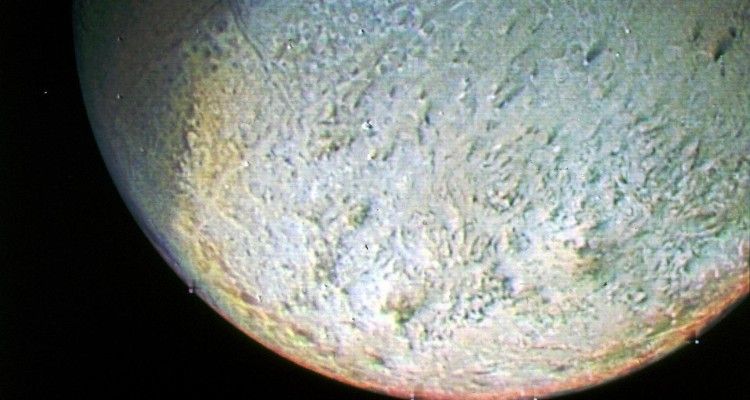

Triton (Neptune) – 2,707 km

- Diameter: 2,707 km

- Size compared to Earth’s Moon: 77.9%

- Year discovered: 1846

Triton is Neptune’s biggest moon, discovered in 1846 by William Lassell. What makes it fascinating is that it orbits backward (called a retrograde orbit), opposite to Neptune’s rotation. That’s a big clue that Triton wasn’t originally part of Neptune’s system but was probably captured from elsewhere in the solar system.

Another wild thing about Triton? It has ice volcanoes. Instead of lava, these volcanoes erupt nitrogen gas and frozen material. When Voyager 2 flew by in 1989, it even caught geysers shooting nitrogen straight into space. That kind of activity is rare on moons.

Triton’s surface is covered in ice, and there’s a chance that liquid water exists deep below. If so, it could be one of the few places in the solar system where life might be possible. It also has a super-thin atmosphere made of nitrogen, but don’t expect to breathe there.

6

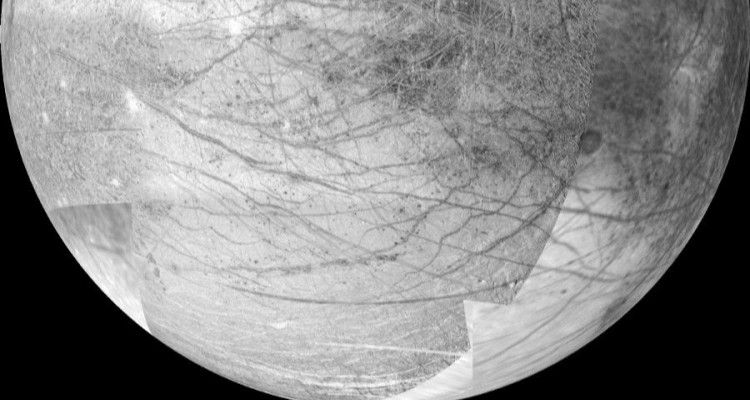

Europa (Jupiter) – 3,122 km

- Diameter: 3,122 km

- Size compared to Earth’s Moon: 89.8%

- Year discovered: 1610

Europa is one of Jupiter’s biggest moons and easily one of the most interesting. Its surface is covered in cracked ice, with long, dark streaks that suggest the ice shifts and moves over time. Beneath that frozen shell, scientists believe there’s a massive ocean of liquid water that’s kept warm by heat from the moon’s interior.

Because of that hidden ocean, Europa is considered one of the best places to look for alien life. If life can exist in Earth’s deep oceans near hydrothermal vents, it’s possible something similar could be living in Europa’s waters.

NASA is planning to take a closer look with the Europa Clipper mission, set to launch in the 2030s. The spacecraft will scan the surface, study the ice, and look for signs that Europa’s ocean might actually be habitable.

5

The Moon (Earth) – 3,475 km

- Diameter: 3,475 km

- Size compared to Earth’s Moon: 100%

- Year discovered: Prehistory

Earth’s Moon is the only one we’ve got, but it’s still pretty special. It’s the fifth-largest moon in the solar system and likely formed billions of years ago when a Mars-sized object slammed into Earth. This theory is known as the Giant Impact Hypothesis.

Its surface is covered in craters, mountains, and dark plains called maria, which were created by ancient volcanic activity. Unlike any other moon, humans have actually set foot on it, thanks to the Apollo missions between 1969 and 1972.

Besides lighting up the night sky (isn’t it beautiful?), it also controls Earth’s tides and helps keep the planet’s rotation stable. Without it, life on Earth would be very different.

4

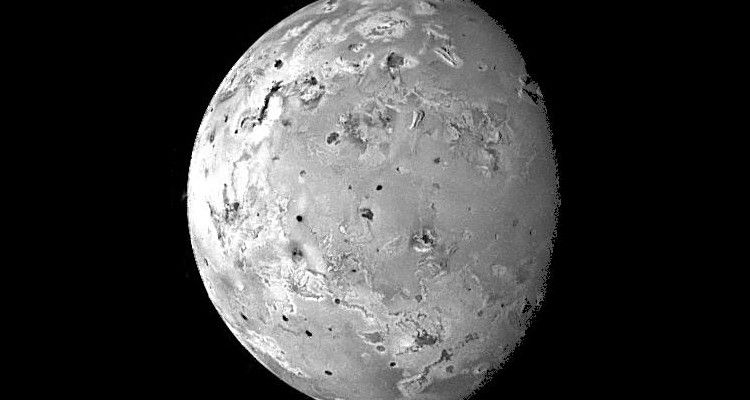

Io (Jupiter) – 3,643 km

- Diameter: 3,643 km

- Size compared to Earth’s Moon: 104.8%

- Year discovered: 1610

Io is basically a giant volcanic hotspot. It’s the most volcanically active place in the solar system. It’s constantly spewing out sulfur and lava, which gives it that weird yellow-orange, pizza-like appearance.

Unlike most moons, Io doesn’t have many craters. That’s because its surface is constantly getting resurfaced by lava, covering up any impact scars almost as soon as they form.

What keeps Io so active? Jupiter’s intense gravity (plus the tug from nearby moons like Europa and Ganymede) stretches and squeezes Io’s interior, generating enough heat to keep its volcanoes erupting nonstop. It’s a chaotic, lava-filled world. Probably not a place you’d want to visit.

3

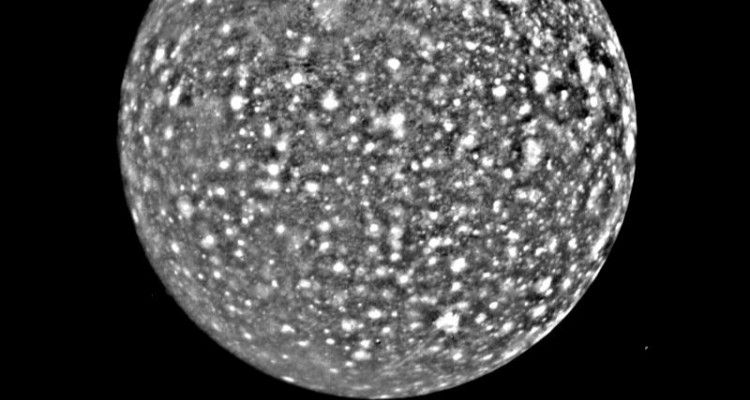

Callisto (Jupiter) – 4,820 km

- Diameter: 4,280 km

- Size compared to Earth’s Moon: 138.7%

- Year discovered: 1610

Callisto is Jupiter’s second-largest moon, and if there’s one thing that stands out about it, it’s the craters. In fact, it’s considered the most heavily cratered object in the solar system, meaning its surface has been unchanged for billions of years. It’s basically a time capsule from the early solar system.

Unlike some of Jupiter’s other big moons, Callisto is pretty geologically dead. No volcanoes, no shifting ice, no signs of a subsurface ocean. Just a cold, battered landscape that’s been collecting impact scars for eons.

That being said, Callisto has one thing going for it. It’s far enough from Jupiter to avoid the worst of the planet’s radiation. Some scientists think this makes it a good candidate for a future human base, since it would be one of the safest places to set up camp in the Jupiter system. I probably wouldn’t live there, though.

2

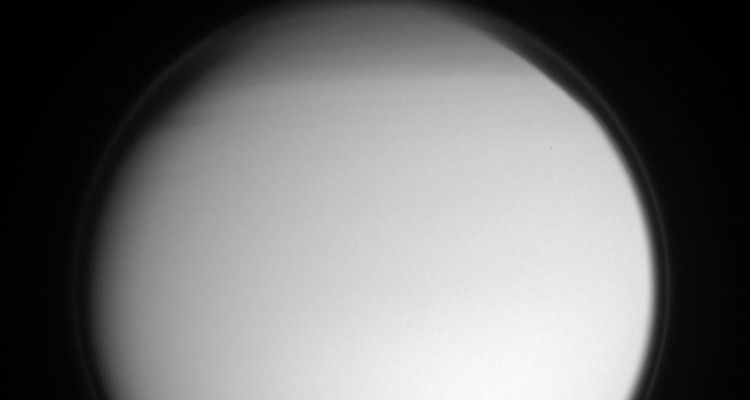

Titan (Saturn) – 5,150 km

- Diameter: 5,150 km

- Size compared to Earth’s Moon: 148.2%

- Year discovered: 1655

Titan is Saturn’s biggest moon, discovered way back in 1655 by astronomer Christiaan Huygens. It has a thick, hazy atmosphere, mostly nitrogen with a bit of methane, which makes it the only moon in the solar system with a real atmosphere.

Below that thick orange sky, Titan has lakes and rivers, but instead of water, they’re filled with liquid methane. It even has a rain cycle, just like Earth, except it rains methane instead of water.

Scientists also think there might be a huge ocean of liquid water hidden beneath its icy crust. If that’s true, Titan could be one of the few places in the solar system where life might exist. The Cassini spacecraft and the Huygens probe gave us our first real look at this strange world, but there’s still a lot left to discover.

1

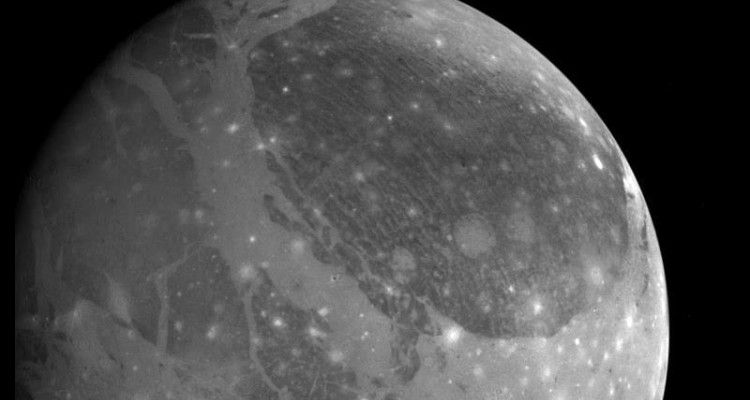

Ganymede (Jupiter) – 5,270 km

- Diameter: 5,270 km

- Size compared to Earth’s Moon: 151.7%

- Year discovered: 1610

Ganymede is the largest moon in the solar system, even bigger than the planet Mercury. If it were orbiting the Sun instead of Jupiter, it might have been classified as a planet.

Ganymede is the only moon with its own magnetic field. Scientists also think there’s a huge ocean buried underground, possibly holding more water than all of Earth’s oceans combined.

NASA’s Galileo spacecraft gave us our best look at Ganymede’s surface. It showed icy plains, craters, and a mix of grooves and ridges which means there was probably some past geological activity.

Now, the European Space Agency’s JUICE mission is set to visit Ganymede in the 2030s to take an even closer look to figure out just how deep that hidden ocean goes.

We’ve given you all the juicy details, but here’s a table to put all of this into perspective at a glance:

|

# |

Moon |

Diameter (km) |

Size Compared to Earth’s Moon (%) |

Planet |

Year Discovered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Oberon |

1,523 |

43.8 |

Uranus |

1787 |

|

2 |

Rhea |

1,529 |

44 |

Saturn |

1672 |

|

3 |

Titania |

1,578 |

45.4 |

Uranus |

1787 |

|

4 |

Triton |

2,707 |

77.9 |

Neptune |

1846 |

|

5 |

Europa |

3,122 |

89.8 |

Jupiter |

1610 |

|

6 |

The Moon |

3,475 |

100 |

Earth |

Prehistory |

|

7 |

Io |

3,643 |

104.8 |

Jupiter |

1610 |

|

8 |

Callisto |

4,820 |

138.7 |

Jupiter |

1610 |

|

9 |

Titan |

5,150 |

148.2 |

Saturn |

1655 |

|

10 |

Ganymede |

5,270 |

151.7 |

Jupiter |

1610 |