Bootleg games and not-so-subtle knockoffs are usually frowned upon in the gaming industry. They either get shunned by fans for lacking originality or incur legal action from companies fearing competition. But in some cases, bootlegs and clones have propelled the success of the games they imitate.

4

Shin Megami Tensei

The creation of the monster-taming genre—which encompasses any game centered around capturing and battling a wide variety of collectible creatures—is often credited to Nintendo’s Pokémon Red and Blue. However, the immensely popular genre debuted years earlier with the start of the Shin Megami Tensei franchise—also known simply as Megami Tensei.

The first game to feature a prominent monster-catching mechanic was the 1987 Famicom version of Digital Devil Story: Megami Tensei—the first game in the Megami Tensei series. Digital Devil Story is a traditional turn-based dungeon crawler in which you’ll encounter an assortment of demonic foes. Rather than having a stable cast of party members, the game only provides you with two playable human characters. The rest of your party will have to be recruited during battles by negotiating with enemies, which involves offering items or cash in exchange for their alliance. You can also acquire demons by visiting cathedrals scattered throughout the game world, where you can fuse your demons to create new monsters.

Later Shin Megami Tensei games feature expanded versions of the negotiation mechanic, while some spin-offs replace it with alternative ways of capturing demons. Persona 3 allows you to acquire monsters by completing a mini-game after every battle, and Soul Hackers 2 requires you to complete optional quests to recruit certain demons.

Nintendo reused this monster-taming idea for its Pokémon series, yet it quickly overtook Shin Megami Tensei as the face of the monster-taming genre. Other monster-taming games have tried to rival Pokémon by replicating its family-friendly appeal. Even newer games like Cassette Beasts and Palworld still try to emulate the casual gameplay and colorful designs popularized by Pokémon.

Pokémon has undoubtedly outperformed its original inspiration, but its success has also given Shin Megami Tensei an advantage over its competition. Whereas other monster-taming games are designed for younger players and casual audiences, Shin Megami Tensei has set itself apart as the definitive M-rated alternative to Pokémon.

Shin Megami Tensei is notorious for its apocalyptic stories, mature subject matter, and brutally unforgiving difficulty. The series delivers the challenging gameplay and darker storytelling that many older Pokémon fans have wanted for years, while also appealing to any fans of hardcore turn-based RPGs. The comparisons between Shin Megami Tensei and Pokémon have never fully died down—and probably never will—but that’s only continued to benefit the series, as proven by the recent successes of Shin Megami Tensei V and Persona 3: Reload.

3

Puyo Puyo

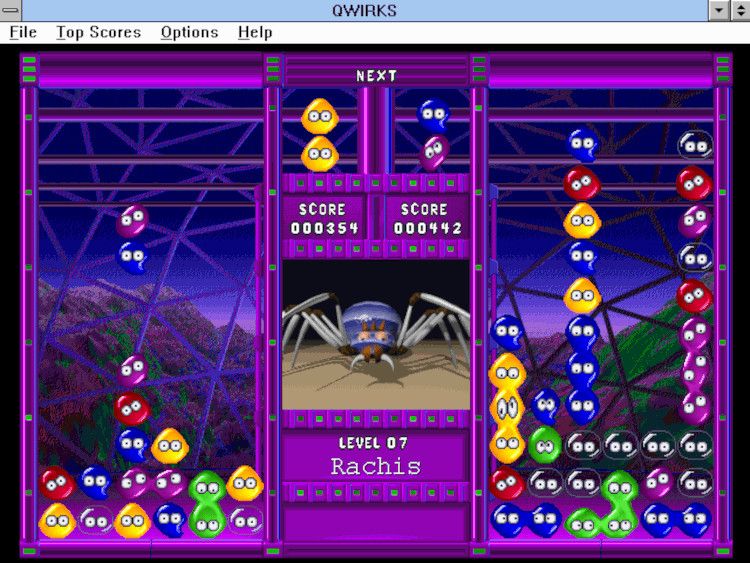

Even if you’ve never heard of Sega’s Puyo Puyo series, you’ve probably seen at least one of its many clones. Puyo Puyo is a falling-block puzzle game—similar to Tetris—in which you position falling blobs on a narrow grid, and score points by connecting four blobs of the same color. While Puyo Puyo does share many similarities with Columns—another Sega-developed series—its faster gameplay and vibrant anime aesthetic give the series its own distinctive personality.

Many early Puyo Puyo games were exclusively released in Japan, and the few entries that did receive an international release were often rebranded with recognizable franchises. The Sega Genesis version of Puyo Puyo was released as Dr. Robotnik’s Mean Bean Machine, which swapped the Puyo Puyo cast with characters from the Adventures of Sonic the Hedgehog animated series. Similarly, Kirby’s Avalanche for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System replaced Puyo Puyo‘s visuals with characters and music from the Kirby series. Even when Puyo Puyo wasn’t being redressed with popular franchises, publishers were still re-releasing the game under different titles like Qwirks.

The abundance of Puyo Puyo games inspired a flood of clones from other developers. Some clones were based off of other recognizable properties, such as Timon & Pumbaa’s Jungle Games (based off The Lion King) and Puzzle Arena Toshinden (a spinoff of Battle Arena Toshinden).

Sega later reused Puyo Puyo‘s gameplay to create Baku Baku—another arcade game with nearly identical gameplay—which then received its own knockoffs, with the most notable being Capcom’s Super Puzzle Fighter II Turbo. Trying to keep track of all these Puyo Puyo knockoffs became very complicated, to say the least.

Although they were meant to replace Puyo Puyo for international audiences, the rebranded Puyo Puyo games still helped popularize the series outside of Japan. Many fans who grew up playing Dr. Robotnik’s Mean Bean Machine, Kirby’s Avalanche, or similar imitations eventually found the same nostalgic fun in the official Puyo Puyo games. Without the success of its many clones—both official and unofficial—there’s a good chance Puyo Puyo would never have had the same worldwide success as it does today.

2

The Sumerian Game

Unless you have an interest in lost media, you’ve probably never heard of The Sumerian Game. Unlike the other games on this list, The Sumerian Game was never released in stores. It was developed as part of a collaborative study between IBM and New York State’s Board of Cooperative Educational Studies (BOCES), which examined the potential benefits of using computer games for educational purposes.

The Sumerian Game was meant to teach basic economic concepts by tasking players with the difficult goal of managing the ancient city of Lagash across multiple decades. This involved maintaining Lagash’s food supply, managing its workers, and expanding the city. While records from the study provide some details about The Sumerian Game, the game itself was never made publicly available. After being used for studies in 1964 and 1968, The Sumerian Game and most of its original assets seemingly vanished.

Not long after, The Sumerian Game was unofficially revived by developer Doug Dyment, who heard someone describe the game while attending a talk at the University of Alberta. Using this description as his sole reference, Dyment developed a heavily simplified version of the original game in 1968 titled King of Sumeria for the FOCAL programming language.

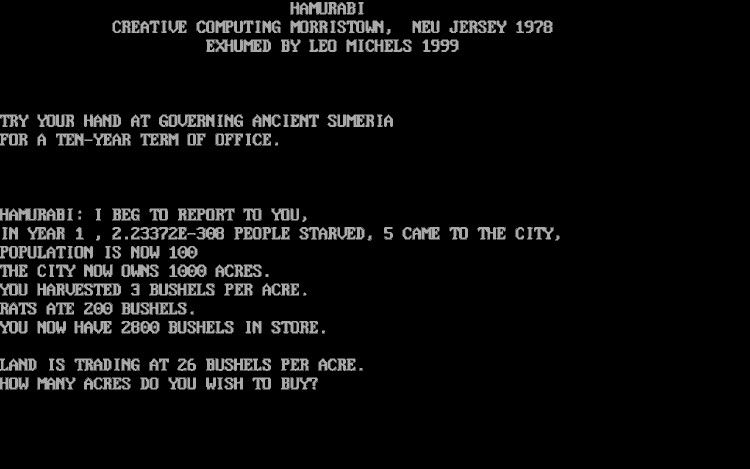

In 1971, an updated port of King of Sumeria—titled Hamurabi—was developed by David H. Ahl in the BASIC programming language. The game’s code was later included in his 1973 book 101 BASIC Computer Games and the 1978 book BASIC Computer Games. Hamurabi was the way that most people experienced King of Sumeria and inspired the creation of many similar strategy games. Some of these were straightforward knockoffs of Hamurabi, while others expanded Ahl’s version with new features. These Hamurabi clones eventually evolved into the city-builder genre, paving the way for other influential titles like Sim City and Sid Meier’s Civilization.

It’s because of Hamurabi‘s popularity that The Sumerian Game is still remembered today. Fans and video game historians traced Hamurabi‘s history back to Dyment’s King of Sumeria and eventually rediscovered their shared connection to The Sumerian Game.

Since then, there have been numerous projects dedicated to restoring The Sumerian Game in its entirety, including a recent remake based on recovered documents from the game’s development. Without King of Sumeria, Hamurabi, and the countless clones that followed, The Sumerian Game would have been a forgotten footnote in gaming history.

1

The King of Fighters

The King of Fighters has an extremely unusual history. In the United States and most parts of Europe, KOF and its developer—SNK—are still relatively niche compared to other prominent franchises like Street Fighter and Mortal Kombat. Yet KOF is a global sensation, often considered just as important—if not moreso—to fighting game communities around the globe.

The series is especially notable for its popularity in Latin America, Mexico, and China, with many of its top professional players hailing from these regions. Few video game franchises have a reputation that’s as unevenly spread as The King of Fighters, but that’s a result of the unique conditions that shaped the series’ success.

Throughout the 90s, when arcades were still booming in the U.S. and Japan, SNK released its arcade games on the Neo Geo MVS (multi-video system) arcade board—not to be confused with the Neo Geo home console. Unlike other arcade boards of the era, the Neo Geo MVS included six cartridge slots for running games.

This not only meant SNK’s arcade cabinets could support multiple games at once, but also allowed cabinet owners to swap out old games for new releases. At the time, KOF games were still being released on an annual basis, so the cartridge format provided an affordable way for arcade owners to keep up with SNK’s constant output.

Possibly the most important aspect of the Neo Geo MVS was its low import costs. Whereas arcades were simultaneously profitable and affordable in the United States and Japan, the arcade industry in many other countries was hampered by high tariffs. Acquiring popular arcade cabinets from acclaimed fighting game developers like Capcom or Midway was too expensive for many arcade owners in these territories. By comparison, the low price and long-term value of the Neo Geo MVS made it far more accessible for overseas arcade owners, allowing SNK to dominate the arcade industry in these countries.

The Neo Geo MVS’s low price wasn’t the only reason it became popular in overseas arcades. Besides being affordable, the Neo Geo MVS was also infamously easy to bootleg. Since SNK was using the same exact hardware to support all of its arcade games, bootleggers quickly learned to reproduce the Neo Geo MVS cabinets and distribute them at an even lower cost.

Additionally, the cartridge-based format of the Neo Geo MVS also allowed third-party developers to produce bootlegged reproductions and unlicensed games for these cabinets, including the infamously unbalanced KOF 2002 Magic Plus II.

Despite the rampant piracy affecting SNK’s releases, these bootlegs didn’t take away business from the company. If anything, they boosted the popularity of SNK’s franchises worldwide.

In Mexico and Latin America, KOF cabinets greatly outnumbered other fighting games in arcades, placing them at the center of fighting game communities across the globe. Even after SNK discontinued its Neo Geo MVS arcade boards, The King of Fighters continues to boast a massive global following and is still a prominent fixture in arcades around the world.

The modern video game industry is filled with petty lawsuits and pointless antagonism against unofficial projects, but these games prove that these projects can be beneficial for gaming franchises. Whether they bring more attention to an underrated series or revitalize forgotten franchises, clones and bootlegs can be surprisingly effective at boosting the recognition of lesser-known games.