Blackrock’s chief investment officer of global fixed income told CNBC on Wednesday that the world’s largest asset manager had “started to dabble” in bitcoin.

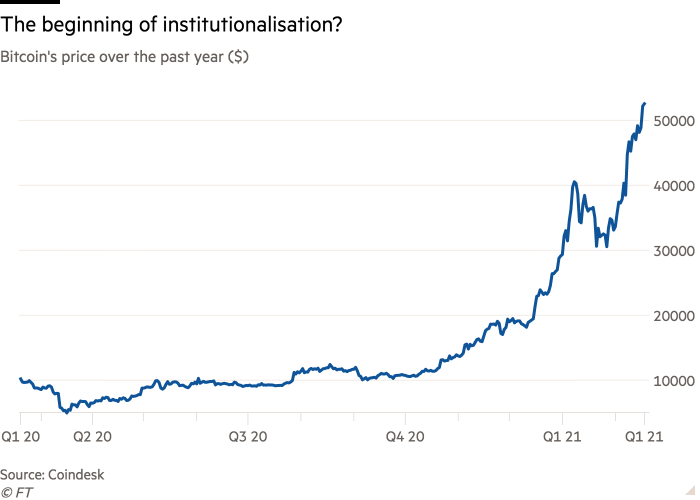

This was all the excuse bitcoin needed to charge ahead to a new record high of $52,533.

The institutional buzz around bitcoin started when US-listed Microstrategy, a business intelligence company, revealed in August 2020 that the company had invested $250m of its excess cash in bitcoin as a hedge against the dollar.

One inadvertent consequence of the treasury management move was that Microstrategy’s shares would soon be considered a precious “listed” proxy for owning bitcoin outright, especially by those money managers bound by strict risk-controlled investing mandates that stop them dabbling in crypto.

The incident proved a gateway moment for institutional interest in bitcoin, culminating in December’s big reveal by Ruffer, the UK-based asset manager, that it too had made a primary investment worth £550m.

Bitcoin has been on a tear ever since then, propelled even higher in recent weeks by electric carmaker Tesla’s announcement that it too has been diversifying its treasury holdings into the crypto asset.

The truly big question is what does it mean for bitcoin now that institutional names are dipping their toes in the asset class and potentially bringing major money inflows with them (beyond the obvious of “number go up”).

A commodities investing echo?

One good precedent to look at is the impact pension funds had on commodity prices when they similarly decided around 2005/6 that they needed to look to alternative investments to diversify against their dollar exposure.

While the idea of pension funds investing in commodities such as oil, metals and even agricultural goods (usually through futures) is entirely normal today, back in the mid-noughties it represented a big step away from conventional money-managing mandates. The big point of controversy at the time was the lack of yield (a source of controversy with gold itself as well) and hence the overt price risk this would expose the funds to.

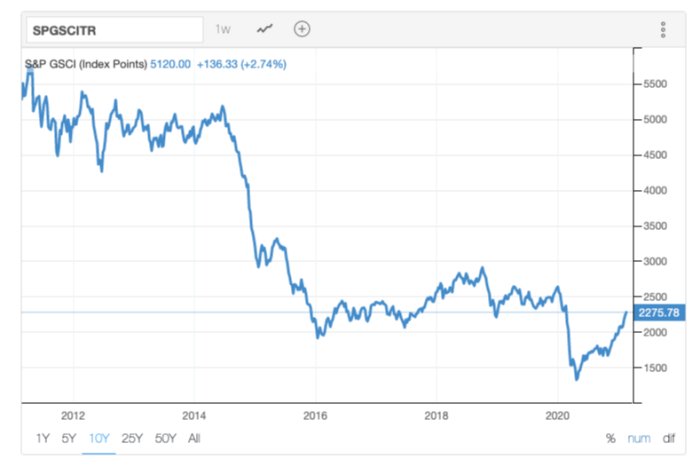

To lower the risk, pension funds and institutional managers mostly piled into commodity index products that tracked the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index (GSCI) or into commodity ETFs.

Institutional money’s collective impact on the commodities futures curve over this period is still hotly debated, but it has long been theorised that it may have contributed to the overpricing of commodity futures relative to their spot-price fundamentals, leading to the normalisation of a contango structure in commodity prices, especially after the 2008 financial crisis.

This, in turn, sent a signal to the market to keep producing commodities irrespective of natural demand because the contango structure made it financially lucrative to produce for the simple purpose of storing rather than consuming them.

None of this would have been financially viable if not for the institutional wall of money sitting on the futures curve happy to lose value at every consecutive monthly roll of futures positions into a contango structure. The effect of this was a negative yield for such commodity investing funds.

For as long as the price of commodities kept going up to compensate for the yield destruction the positions proved manageable. But once commodity prices reversed, it didn’t take too long for institutions to figure out sitting idle on the curve was a lossmaking strategy that could be exploited by physical producers and trading houses on the ground. When that happened, backwardation returned to the market unlocking all the previously stored-up commodities that had been funded by the contango structure.

The effect was a total collapse in the price of commodities (led by oil) over the course of 2015 (GSCI chart courtesy of Trading Economics):

Institutional crypto yield generation?

Unlike core commodity markets, bitcoin’s futures are illiquid and immature. Even so, the natural state of bitcoin’s futures curve has for a long time (much like gold’s) tended towards a contango structure, not backwardation like it does with most other commodities. This is down to its financialised nature.

The other big difference with bitcoin is that, unlike bulky industrial commodities, which require active professional and expert management to physically hold, the crypto asset can be easily stored by institutional managers.

These two elements are important because they provide institutional managers with the opportunity not just to expose themselves to higher bitcoin prices, but also (if they wish) to lock-in a healthy yield with their holdings.

For as long as the bitcoin curve remains in contango, that means it’s a very different proposition for institutional managers than commodity investing was. (For more on how contango trades work, see here.)

How a bitcoin contango trade (and you can bet your bottom cryptodollar there will be hedge funds already doing so) works in theory is simple.

An institution buys physical bitcoin ($51,811 at pixel time) but sells a future ($52,045 at pixel time on the CME) at a premium to the price they acquired the original bitcoin for at the same time. The process hedges their exposure to the price of bitcoin (thus removing risk) while locking-in a risk-free yield that can be collected provided the position is held to the settlement point. It pays to put the position on for as long as the yield generated outnumbers the cost of managing and securing the physical bitcoin, and the cost of capital to fund the position.

But there are some caveats to its risk-free nature. The trade is only as riskless as your futures counterparty. (For more about that see here). This is why until bitcoin futures were traded on a reputable and regulated exchange like the CME, which had proper experience in managing risk and margins, anyone conducting the trade was at risk of having their profits wiped out by the non-performance of their counterparty. And in the early era of the bitcoin Wild West that was a bona fide risk.

The launch of CME bitcoin futures, however, heralded in a new risk-controlled crypto era. Not only did CME futures make it possible to short bitcoin without having to worry about counterparty risk, enabling better price discovery in general, they also facilitated the introduction of contango trades. This was especially the case for regulated and creditworthy institutions who had the capacity to both fund the margin capital needed to operate at the CME and met the exchange’s minimum credit standards.

The contango trade as the ultimate HODL

As institutional money moves into cryptocurrency it will become increasingly important to analyse not just what the institutions are investing in but how they are investing in it.

In theory, institutional managers starved of risk-free yield in the core financial sector, should be hugely tempted to synthesise yield with bitcoin contango HODLs.

Whether they do or not, however, will come down to the nature of their investing mandates.

In many cases, despite the free money on the table, the associated security risk and other complexities of holding physical bitcoin could keep the crypto asset out of their reach in pure form. In that case, institutions might choose to buy proxies like Microstrategy, ETFs (as and when they are issued) or, more perilously, futures instead.

If institutional managers did decide to invest most heavily in bitcoin futures, the risk remains they would end up taking the other side of hedge fund or broker/dealer contango trades. This would risk institutions replicating the negative yield exposure they experienced with commodities investing. It would also engineer a compartmentalised system of exposures across the industry.

The signals from the markets would also not be what they seemed. In terms of pure positioning analysis (as derived from CFTC commitment of traders reports), if hedge funds and broker/dealers were indeed playing the contango trade they would appear to be shorting bitcoin even if in reality they were stringently HODLing underlying bitcoin.

Of course, there is one other bitcoin yield-generating strategy that institutions could be inclined to adopt: lending their physical bitcoin holdings for a fee to counterparties for shorting purposes (as they already do with equities). This would become all the more tempting if and when bitcoin’s price began to plateau or depreciate.

If and when bitcoin’s price did stabilise, it might even pay for institutions to compensate for bitcoin’s lack of yield by lending out their holdings to corporations for capital investing purposes, in traditional merchant banking mode.

At which point some clever crypto entrepreneur will propose the creation of an average bitcoin lending rate to benchmark deals against. And we will have not just recreated Libor but anchored it to a settlement system that cannot be bailed out with extraordinary central bank intervention.

And that, in an environment where it’s proving much more difficult to expire old Libor than first appreciated, could be quite a proposition.

Related links:

Markets must speed up efforts to ditch Libor, warns watchdog – FT

2020: The year bitcoin went institutional – FT Alphaville