Most people know that black holes are kind of scary. Admittedly, that’s true, but black holes are so much more than that. They are truly fascinating wonders, from how they form, their many types, and even how they die. Every aspect of black holes is mind-boggling if you know the truth about them.

What Are Black Holes?

Black holes are very complicated, but let’s start with the basics—what they do, where they come from, and where you can find them. Before any of that though, I want to dispel a certain myth about black holes that popular media may have perpetuated (you know what you did, Interstellar).

Black holes are not wormholes. They don’t teleport you to another dimension. They don’t allow you to time travel. They don’t even send you to a different point in space. They are just big masses with so much gravity that they pull in everything around them, like a big space monster that exists only to feed, not a magic gateway to another place.

Granted, we don’t know this for certain since no one has ever gone into a black hole personally, but as far as our theoretical understanding of black holes is concerned, its accurate.

Alright, now that we have that out of the way—a black hole is an area of space where gravity is so strong that no known object can escape its pull beyond a certain point, not even light. This is why they appear black in the first place. You can’t actually see a black hole at all, you can only see the matter around it being pulled into it. After all, if no light from the black hole itself reaches our eyes, we can’t actually see it.

The intense gravity of a black hole forces matter into an incredibly small (relatively speaking) space, so they are incredibly dense. For example, there’s a supermassive black hole in the center of the Milky Way galaxy called Sagittarius A* (said Sagittarius A Star) with four million times the mass of our Sun. You might think that such black holes would be rare, but it’s estimated that the Milky Way alone could contain more than one hundred million black holes, though they aren’t all supermassive. More on that later.

You can find black holes all across the universe because they are formed by substances that are also found almost everywhere—stars and gases. Black holes can form in two ways. The first way comes about when a star of sufficient mass dies. Usually, a supermassive star with a mass at least three times that of our Sun. When these stars run out of fuel, they explode in a supernova, leaving behind an incredibly dense mass, a stellar mass black hole.

All stars die eventually, but those without enough mass to create a black hole when they die often leave a white dwarf or neutron star behind instead. The second way a black hole can form is through direct collapse, though this only happened in the distant past when the universe was first forming. Direct collapse is pretty complicated and was only possible in one specific time period in our universe’s lifespan, around 100-250 million years old.

The gist of it is that you had big clouds of hydrogen and helium in space, bathed in ultraviolet radiation, being crushed into a dense object by dark matter. Ordinarily, such a cloud would cool and fragment, eventually forming stars. However, the presence of all that ultraviolet radiation prevents that, and the gas keeps getting compressed without ever fragmenting, which creates the ideal conditions for a supermassive black hole such as Sagittarius A*.

That said, the conditions for direct collapse black holes are long past, so this method of formation is not possible today, as far as human science is aware. Today, black holes are formed by various other methods, including the deaths of stars and mergers between compact stellar remnants. Despite a limited array of origins, there are still several different types of black holes in our universe.

The Types of Black Holes

There are many different types of black holes: stellar, supermassive, intermediate, and binary. Technically, there is another type, known as primordial black holes, but these are theorized black holes formed in the early days of the universe. These black holes are hypothetical and there is technically no concrete proof that they exist, so for now, we’ll focus on the black holes we know exist.

Stellar Black Holes

Stellar black holes are formed when a star of significant mass dies. When a star runs out of fuel, it collapses in on itself. If there isn’t enough mass, then a white dwarf or neutron star will likely be left behind. But if there is enough mass, the collapse will continue to compress into a very small point (called a singularity), creating a stellar black hole.

These black holes tend to be smaller than other types but are also incredibly dense. For example, a stellar black hole could fit a mass several times more than our Sun into an area as small as a city on Earth. This in turn generates a ton of gravitational force, pulling in other nearby objects, such as dust and gas from the surrounding galaxy. This allows stellar black holes to grow to sizes far beyond the mass of the original star that they formed from.

Supermassive Black Holes

Supermassive black holes are the largest of all the types. They are estimated to have masses millions or billions of times greater than our Sun, even though some of them are smaller—some supermassive black holes are less than half of the Sun’s diameter. It’s believed that a supermassive black hole lies at the center of nearly every known galaxy. Just like stellar black holes, this type can continue to grow to even larger sizes by consuming matter from the galaxy around it.

Scientists aren’t entirely sure how supermassive black holes form, but they do have several theories. Perhaps hundreds or thousands of smaller black holes merge into a supermassive one. Clusters of dark matter could be responsible. Maybe the collapse of an entire stellar cluster could create a supermassive black hole. A popular theory is that supermassive black holes may be the result of direct collapse formation during the early stages of the universe.

While we don’t know the specifics of their formation, the fact remains that supermassive black holes are the biggest of them all in terms of mass.

Intermediate-Mass Black Holes

For the longest time, people figured that black holes only came in two sizes—very small and extremely big. But in somewhat recent years, scientists discovered the in-between model, intermediate black holes. Honestly, there’s nothing particularly special about these black holes. They aren’t as small as stellar black holes, and they aren’t as big as supermassive black holes, and that’s really it.

That said, there is still a lot to be learned from intermediate black holes, as the origin of their formation could lead humanity to a new understanding of how things work in the universe. If these black holes are primordial in nature, they could tell us many things about the early days of the universe. If they have a different means of formation, like successive mergers of black holes or white dwarfs, we could learn something new from that as well.

Currently, the preferred hypothesis is that intermediate black holes form when multiple stars in a cluster collide and create a chain reaction, and their combined mass makes the new black hole that is bigger than a regular stellar black hole, but not as big as a supermassive one. They’re also speculated to exist at the center of dwarf galaxies, which are smaller than the usual kind. For now though, we don’t know how they form for certain.

Binary Black Holes

A binary black hole system is when two black holes are in the process of merging, so they are spinning around each other in a gradually decreasing orbit. They can both be spinning in the same direction or opposite directions. Eventually, these two black holes will merge together, but it can take a very long time for that to happen. Other than their close proximity to one another, there’s nothing unique about these black holes, which are usually just two stellar types. They do produce incredibly intense gravitational waves, however, which astronomers can now measure.

What Do Black Holes Look Like?

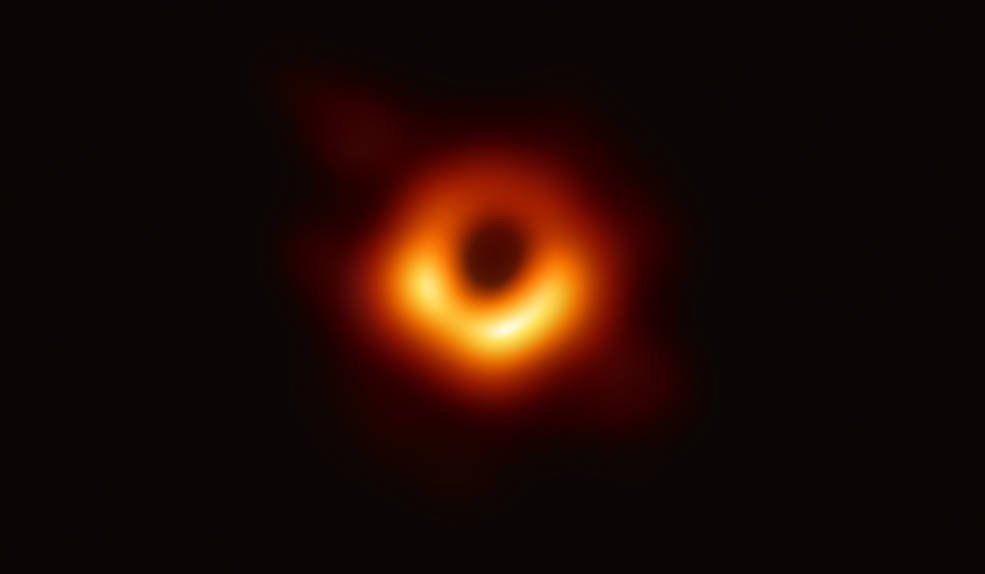

While it’s impossible to actually “see” a black hole with your eyes, scientists have been able to determine what they look like by reading the radiation emissions of black holes as they draw in the mass around them. Sometimes, that material can block the emissions and make it harder to see what a black hole looks like, which is often the case with supermassive black holes. At any rate, humanity has a pretty good idea of what black holes look like.

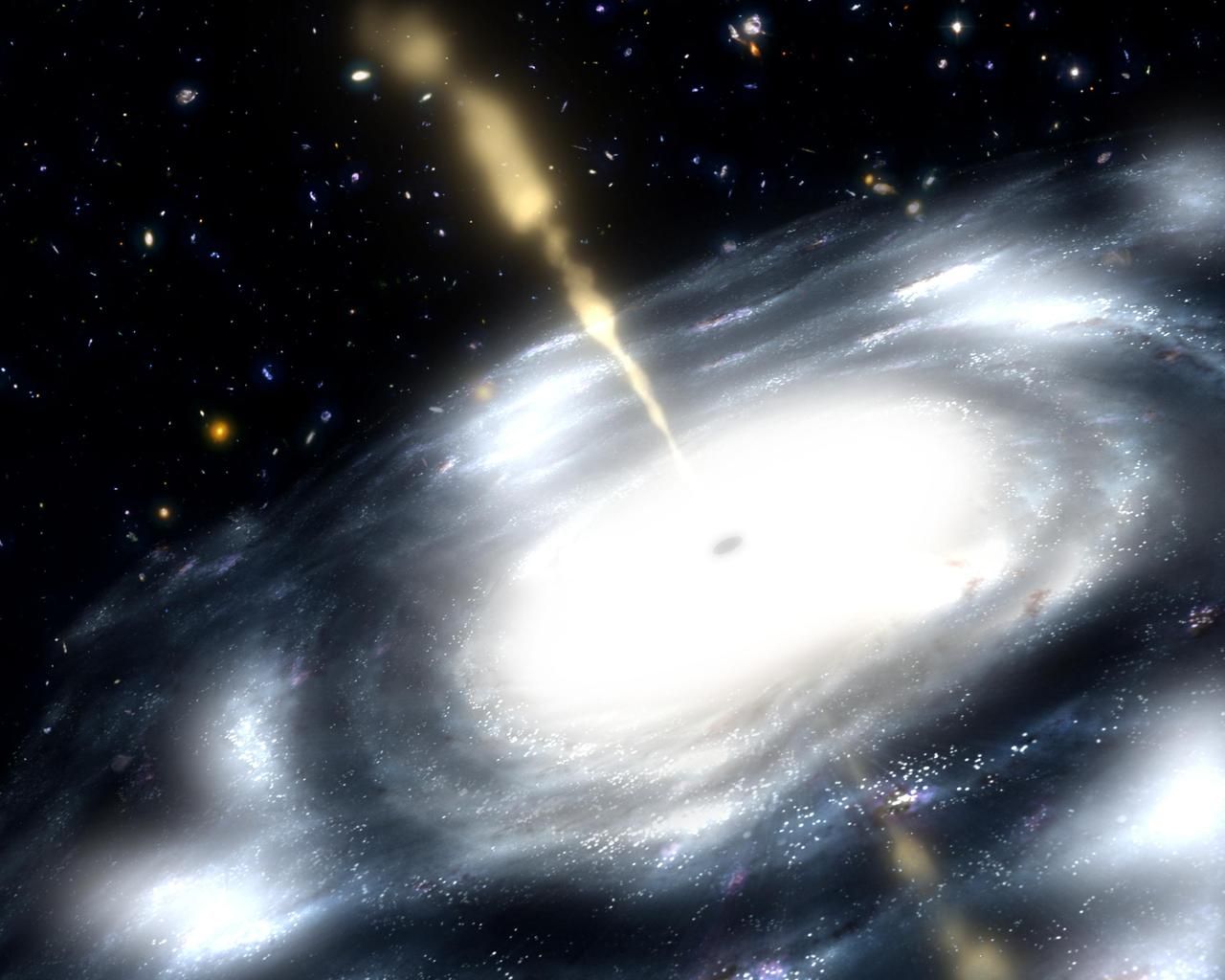

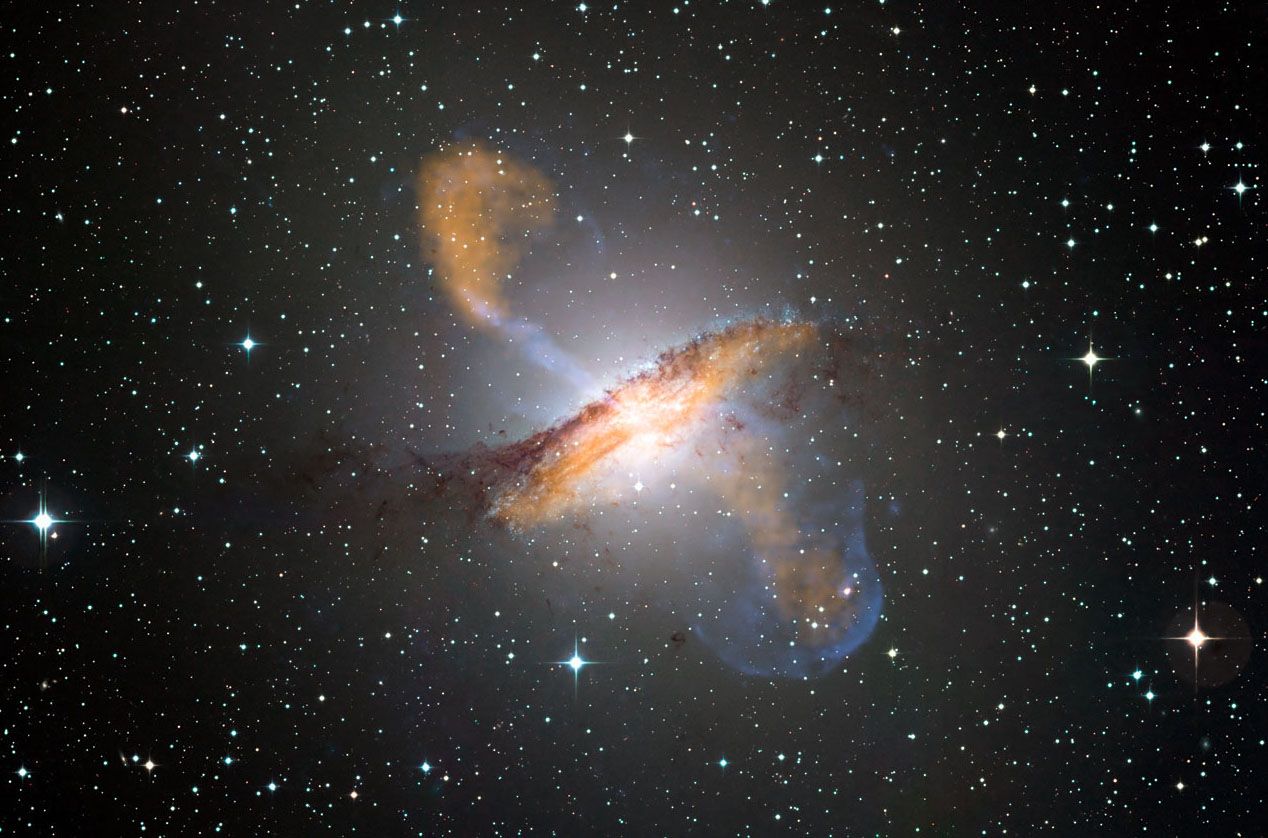

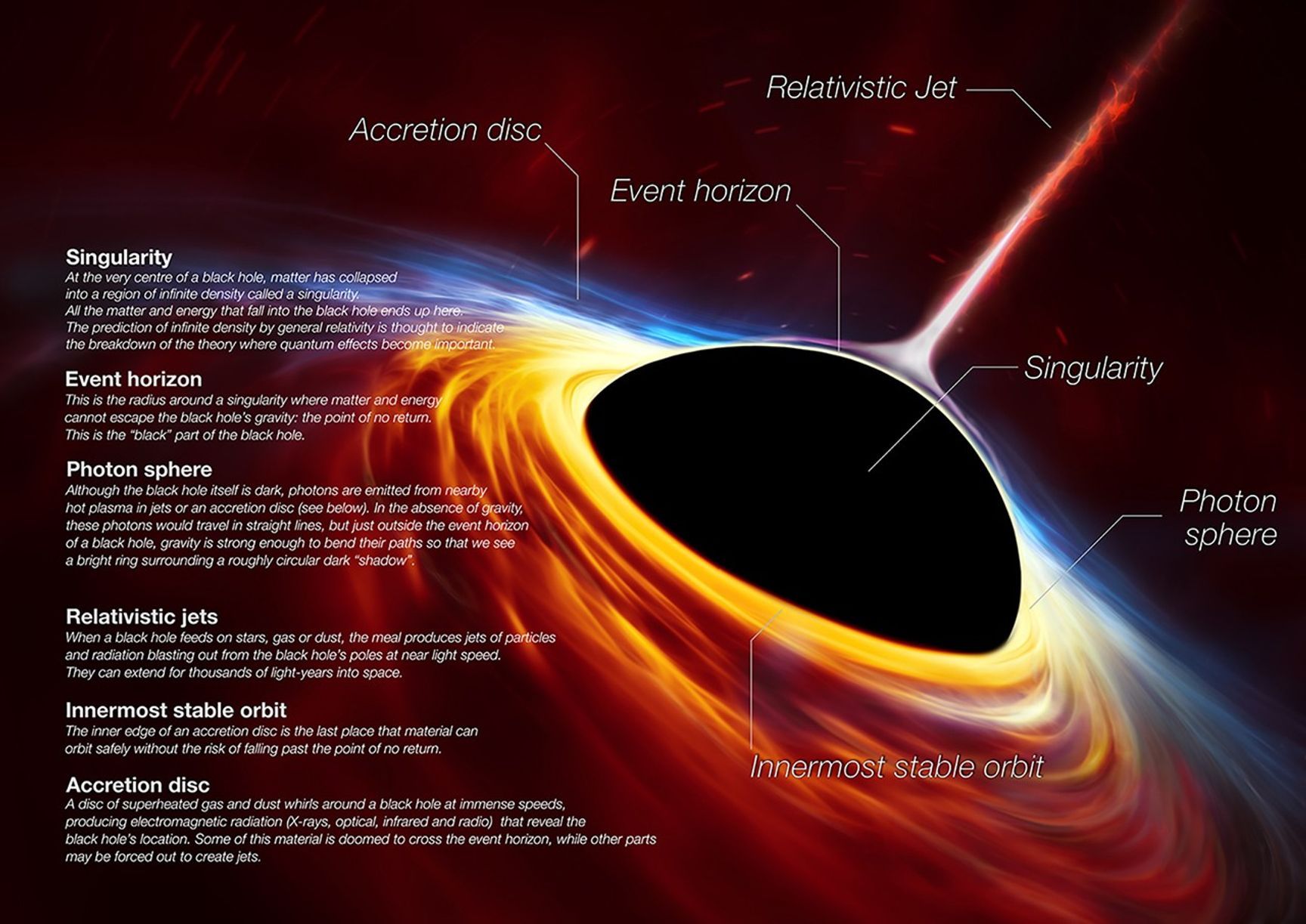

To start, there are three layers: an outer and inner event horizon and the singularity itself. The event horizon is the point where gravity becomes so intense that, if crossed, a particle will not be able to escape. The actual black hole itself, the point in space-time where its mass is located, is the singularity. Occasionally, matter can be ejected away from the event horizon and hurled into space at near light speed, creating bright jets of energy.

So, let’s break down what this all looks like and the parts themselves. For starters, the singularity cannot be seen. This is the very center of the black hole, beyond the event horizon where no light can escape. The event horizon itself is actually the “black” part of a black hole—the big spherical object that you imagine when thinking of a black hole. Just outside the event horizon is a ring of light called the photon sphere.

Photons are emitted by hot plasma from the jets or accretion disk around the black hole. Ordinarily, they would travel in a straight line, but the intense gravity of the singularity bends them around itself, creating a bright ring. Outside of this is the accretion disk, which is a huge swirling mass of all the dust, gas, and other matter the black hole is pulling into itself. This matter is accelerated to near light speed, causing it to emit energy that we can detect and “see.”

Finally, there’s the relativistic jets. These are huge beams of particles and radiation emitted from the poles of the black hole when matter is ejected away from the event horizon and gets shot into space. Relativistic jets are massive and can stretch on for thousands of light years or even hundreds of thousands of light years.

Ultimately, our understanding of what black holes look like is framed almost entirely by instruments, with our actual visual understanding of them limited to a few images taken within the last decade, all of which are kind of blurry. It will probably be some time before humanity can clearly see with our own eyes what a black hole looks like clearly.

Black holes are incredibly mysterious, and though we know a lot about them, there are always new discoveries to be made about these distant maws and their insatiable cosmic hunger. Unfortunately, they are all too far away to ever investigate up-close, so our research is limited to measurements from instruments we have here on Earth. Even so, there’s little doubt that we’ll uncover more amazing things about black holes in the future.