One of the streaming platforms that pays out the highest amount of artist royalties for every song played isn’t Spotify, Apple Music, or the supposedly artist-friendly Tidal—it’s Peloton. That is to say, not a streaming service, but the luxurious, glitzy fitness company, whose recent megapopularity has been matched only by its controversy.

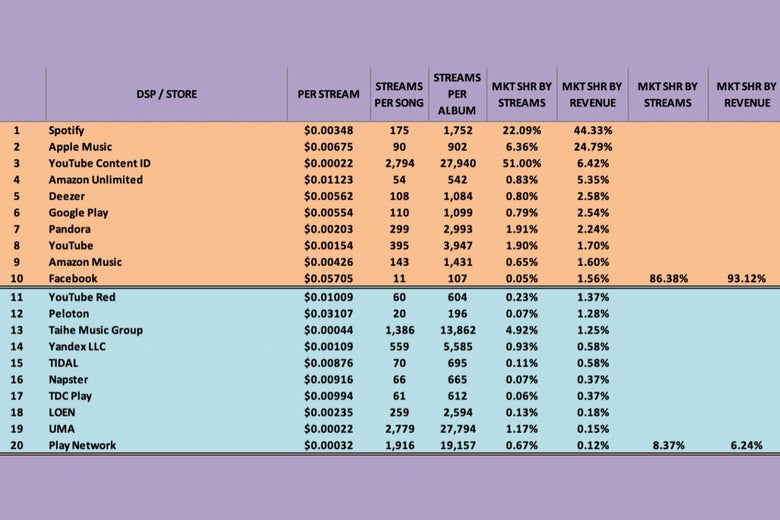

Per music industry blog the Trichordist’s most recent “Streaming Price Bible,” Peloton’s payout rate per stream based on 2019 measurements was a whopping 3.1 cents, far exceeding the fractions offered to music rights holders by Spotify (0.35 cents), Apple Music (0.68 cents), YouTube (0.15 cents), and Tidal (0.88 cents), among others.

This is not to say that Peloton is the single highest-paying music platform worldwide or a flush treasure chest for music businesspeople. Peloton is still bested in the per-stream business by Facebook, which pays out nearly 6 cents, according to Trichordist (the platform offers direct monetization channels for artists and has deals with labels for songs streamed over its gaming platform). Plus, the fitness brand isn’t a significant part of the streaming economy (at least, not yet): More than half of global licensed music streams are logged on YouTube, while Spotify brings in nearly half of the global music business’s streaming revenue; meanwhile, Peloton only accounts for 0.07 percent of global streams and 1.28 percent of industry revenue. (Facebook likewise holds a meager place in the streaming market, hosting even fewer streams than Peloton.) Still, the fact that the weird home exercise equipment corporation—er, sorry, media company—is one of the most potentially lucrative platforms for musicians is yet another bizarre vagary of the modern music industry. It’s even stranger when you consider that Peloton’s payout rate was higher in previous years, averaging about 5 cents a stream in 2017 and 4 cents a stream in 2018.

What gives? Why does Peloton pay artists more than the far more widely used Spotify? Why is this still the case, even after Peloton’s payout rate has dropped steeply year after year? Which musicians get the privilege of a Peloton check, and how much of that money do they really see, anyway? If my bringing up these facts alone has left you befuddled, fear not—I am here to clarify the bizarre economics of the digital-fitness-music-streaming world.

So … what’s Peloton’s deal with music streaming?

As you’re well aware if you’re a regular Peloton user, the service’s music selection has been a significant part of the experience for years, as the key soundtracks for its spin classes and other virtual workouts. Peloton’s prospectus states that “members consistently rank the music we provide as one of their favorite aspects of the Peloton experience.” Peloton’s co-founders themselves stated that they wished to “creat[e] a Members-first experience [that] would require Peloton to be as vertically integrated as possible”:

We have developed a proprietary music platform that fuels the workout experience with thoughtfully curated playlists that align with our Members’ musical preferences. We have over a million songs under license, representing the largest audiovisual connected fitness music catalog in the world. Our curated music … deliver[s] a custom-fit-and-finish musical experience created by instructors and music supervisors on our production team. … Peloton is a discovery resource for new artists and songs while also providing the opportunity for our Members to re-discover music they love. … We believe we have defined a new standard for musical content development in the fitness and wellness categories, which includes premiering new music, working with artists to co-curate classes based on their own music or influences, and partnering to create new music.

Whoa, uh, sign me up?

If you like, you may subscribe: As told by Peloton’s website, a $39-per-month all-access membership can net you “endless” opportunities to “move to the music of your favorite artists to find a workout that fits your every mood.” (This particular feature is not touted for the $12.99-per-month digital membership, although that option allows you to use Peloton’s app to “access thousands of classes,” which also use music, of course.) Those subscription prices encompass the costs needed to retain the music for your enjoyment, according to one of Peloton’s 2019 quarterly reports: “Our subscription cost of revenue generally increased each quarter as a result of increases in music royalties, streaming, and platform costs.” (Not all music used by Peloton feeds into these expenses, however: The company also offers a “scenic rides” feature using royalty-free music.)

And there’s another tricky slice to that subscription pie. The company can “enter into agreements whereby we are released from all potential licensor claims regarding our alleged past use of copyrighted material in our content in exchange for a mutually-agreed payment,” reads one of those quarterly statements. To translate: Under a certain type of financial deal with a music company, Peloton isn’t liable for past uses of the songs that company has the rights to. Expenses made to compensate artists for use of their music prior to the date of the deal are known as “content costs for past use,” which are—you guessed it—also incorporated into that subscription pricing.

OK, but how did Peloton already hold music by artists like Jason Derulo on offer?

Again, from the prospectus: “We depend upon third-party licenses for the use of music in our content. … We enter into agreements to obtain licenses from rights holders such as record labels, music publishers, performing rights organizations, collecting societies, artists, and other copyright owners or their agents.” But keep in mind: “We cannot guarantee that we currently hold, or will always hold, every necessary right to use all of the music that is used on our service, and we cannot assure you that we are not infringing or violating any third-party intellectual property rights, or that we will not do so in the future.” So, you know, some of the music on there might not be used legally either, but what can you do? At any rate, it was alleged by one company in 2019 that Peloton “obtained a license for a limited time but then let that license expire, while continuing to use [its] copyrighted works.”

So how does all that affect the streaming royalties payout?

Read on: “With respect to musical compositions, in addition to obtaining publishing rights, we generally need to obtain separate public performance rights.” These public performance rights (along with the publishing bundle) are what really contribute to the higher payout rate.

To understand why, you have to understand the two different types of royalties offered through the vast digital music market: mechanical royalties and performance royalties. Mechanical royalties are paid upon the production or transaction of particular units of music, like vinyl or digital files or individual plays; third-party outfits that record, manufacture, and distribute copyrighted music are paid and subsequently parcel out funds to artists. Performance royalties are paid when music is, well, performed in a live venue, either as part of a film or TV show’s soundtrack or streamed in some form of public setting. On-demand streaming services like Spotify, through which users who don’t own particular recording copies of a song nonetheless have the ability to play said song when they want, pay artists both mechanical royalties and performance royalties. By paying performance royalties for its song streams, Peloton considers itself to be a different type of music broadcaster, more akin to radio than a record player. Users may look for playlists and videos that feature a certain artist or a certain song, but both the entire experience of hearing the music and the playlist including that song are curated by the instructors—not by you.

Why do performance royalties get paid out differently than mechanical royalties?

Because they respectively get transferred through different middlemen. It’s all way too complicated to break down in full here, but there are different copyrights for the static elements of a song (lyrics, melody, arrangement) and for a particular recording or expression of that song (the song’s audio itself, or that of a cover version or live recital). The former is known as composition copyright, the latter as master copyright. There are specific organizations that control master copyrights and, thus, performance rights. These organizations are different from the ones that control the more fixed types of music rights (publishing, songwriting, etc.).

Peloton has deals with performance rights organizations, or PROs, including ASCAP, BMI, Global Music Rights, and SESAC. By the terms decided, the fitness outfit gives these PROs a down payment for licenses to hold songs from their catalogs for the company’s use; in turn, Peloton logs how many times particular songs from its selection were streamed, data that are then used by a PRO to divvy up the prepaid royalty pools to its songwriters and publishers.

Platforms like Apple Music have to entangle with PROs and the agency that pays out government-mandated mechanical royalties. Peloton primarily has to worry about paying the PROs an agreed advance fee and providing the stream logs. Those fees are basically on the PROs’ terms—although, as I mentioned above, Peloton managed to also set conditions by which it wouldn’t need to pay PROs for using their music in programs that occurred prior to their established deals. If Peloton had made such a deal with a PRO in 2016, and one of that PRO’s songs was streamed through Peloton about 10,000 times between 2013 and 2015, Peloton wouldn’t have to contribute royalties for any of those prior 10,000 streams.

Uhhhh. What?!

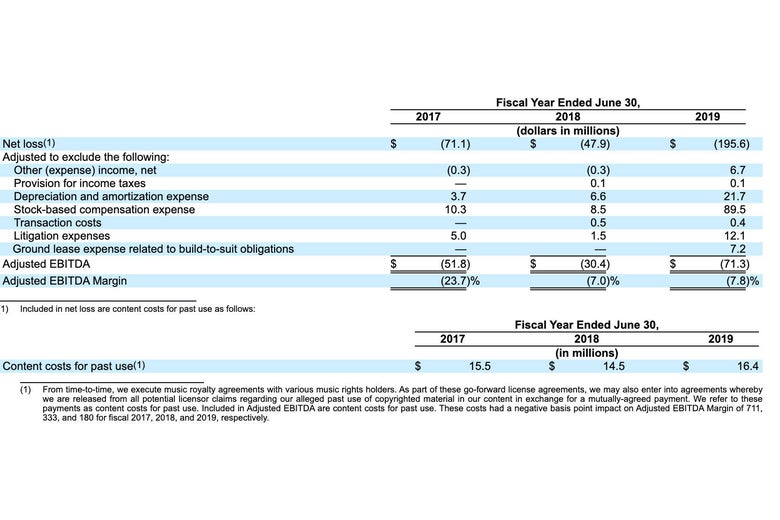

Based on the company’s own financial documents, you can tell Peloton doesn’t love paying for past music uses, referred to internally as “content costs for past use.”

It’s worth noting, while tracking Peloton’s payouts from 2017 onward, that the company has reduced these “content costs” in subsequent years, thanks to yearslong deals; at a certain point, Peloton hopes these royalties costs will “eventually be eliminated” altogether. These deals not only affect how much Peloton pays out per song, but how much it pays out relative to other music platforms.

Yet there are still more factors that regulate the money in Peloton’s case.

You’ve gotta be kidding me.

By March 2018, Peloton started offering a “Just Ride” feature, allowing home equipment users to go on rides without any instruction and accompanying music. But in June of that year, Peloton also acquired Neurotic Media, a service that “connects a brand with a certain popular song or songs that align with their brand mission,” according to TechCrunch. By November 2018, the company had enabled a feature to look up classes by which artists are featured in their playlists. With this adjustment, the Peloton music experience became much less passive and more involved: Instead of randomly listening to whatever songs an instructional video’s teacher curated, a Peloton user could now actively tailor their workout to at least include artists they liked, right from their home bike. Previously, one could filter classes by the genres of their accompanying playlist offerings, but now users could get much more specific by searching even for a particular song title.

That all sounds like Peloton was trying to give its users more control over its curated music experience without having to pay more money to do so.

You’re catching on.

In March 2019, multiple members of the National Music Publishers’ Association, or NMPA, which represents music publishers and their songwriters, sued Peloton for $150 million “in damages over the company’s alleged use of … unlicensed songs,” many from major artists like Lady Gaga and Justin Timberlake. By that time, according to the Cut, Peloton had only paid out $50 million total in music license fees. The primary issue lay with sync licenses, one of the legalities negotiated with PROs that allow a rights holder’s catalog to be used in visual media or an exercise bike’s app. (The Global Health & Fitness Association has a detailed explanation as to why these negotiations are so much more complicated for Peloton than they are for, say, filmmakers.)

And “sync” is just the name for one of the things we already discussed.

Yup. And the association’s claim was that Peloton had selectively procured sync licenses for certain catalogs but not for others—seemingly those of the most high-profile pop stars, whose catalogs are pricey. As TMZ reported in March 2019, Peloton’s founder and CEO sent a letter to subscribers soon after, informing them that “the company is yanking any classes that use the songs ID’d in that lawsuit a handful of music publishing companies filed.” Just a month later, Peloton had countersued, claiming that the association was engaging in anti-competitive conduct. (The Trichordist has a good breakdown of the absurdities of this countersuit, which was eventually dismissed in January 2020.)

I assume these big musicians’ catalogs were probably among the rights that Peloton later stated it “cannot guarantee that we currently hold”?

That’s the most likely scenario. Though we have no proof of this—I’m just going off my assumptions—Peloton’s neglect of those overdue royalties may have been a strategic business decision: As New York magazine writer Amy Larocca told my colleague Seth Stevenson earlier this year, “If you’ve got a little spin studio in Park Slope and you want to play Beyoncé all day, no one cares. But if you’ve got 30,000 people doing your ride, you can’t just play Beyoncé.” The virtual scale Peloton sought ultimately brought more attention to its musical activities—and opened it up to liability.

Kinda like with MoviePass, huh?

Good comparison. While grappling with the suit, Peloton attempted to make nice with its rabid fans, who were disappointed by the “not even good” music left behind, which included repeats of the Now That’s What I Call Music series. One subscriber told Insider in 2019 that this was a factor in her decision to exercise less with Peloton. (Some riders even directly sued Peloton, because the music purge supposedly degraded the overall experience.) So the company expanded its music options further: Its first “Artist Series,” in which musicians directly partner with Peloton instructors to hold classes exclusively scored with their catalogs, was held in June 2019 with Madonna; there have been more since then, with performers like Lizzo, Paul McCartney, and BTS, that have been massive successes for the platform.

Still, scrutiny of the company’s music dealings did not falter, especially as it readied an initial public offering in August 2019. Music Business Worldwide noted that Peloton’s reported payout of $2.8 million over the course of fiscal year 2019 to music rights holders was only 0.3 percent of its annual revenue; factor in the year’s content costs for past use ($16.4 million), which were already falling by FY 2019, and you end up with only 2.1 percent of Peloton’s massive annual revenue going toward its similarly massive music offerings. And the NMPA freshly updated its lawsuit in September 2019, finding more unlicensed songs from artists like Adele and the Beatles in the Peloton catalog and doubling its damages to at least $300 million.

Get their ass.

Indeed. And by February 2020, Peloton and the NMPA had reached a settlement for an undisclosed amount. From then on, Peloton was free to lead the way on fitness brands’ attempts to continually incorporate music in their experiences. Peloton subsequently built what it called an “in-house streaming service,” bought and included the Verzuz series, employed former music industry executives who’d worked with other streaming services and labels, and even used original, app-exclusive music.

OK! But what does all that have to do with why Peloton pays higher amounts per song stream than almost everyone else?

So now that we have laid out all the building blocks of Peloton’s music business as well as its major developments over the past few years, we can recap.

In order to host and broadcast music for the classes it makes available to subscribers, Peloton has to pay PROs for their catalogs, per performance royalty rates negotiated by the PROs. These rates can likely be jacked up to higher amounts than those for more typical streaming services, which have to split between mechanical royalties and performance royalties (with more delegated to the former, thanks to a 2018 government ruling). In earlier years, Peloton paid much more in total royalties annually, since it often (but not always) had to compensate PROs for pre-deal uses of their music. However, more recently, the content costs for past use have nose-dived, and some artists’ catalogs have been entirely removed from Peloton’s service, contributing to the steady fall in average payout rates since 2017.

The flip side is that this also frees up money for Peloton to more faithfully compensate PROs for catalog use following the 2019 lawsuit (which then keeps payouts higher) and to offer funds directly to artists for special partnerships. Getting big-name artists who will actually attract users to Peloton, of course, is not cheap. Peloton could expand its offerings to lower-level or indie artists who are covered in all streaming services, but those artists aren’t as marketable and lucrative.

All right, got it.

Despite these latest developments and rapid-fire build-outs of its music infrastructure, Peloton isn’t a major industry player yet. Its total catalog is paltry, compared with the 70 million tracks available on Spotify, and it has fewer and fewer specific outside royalty channels to compensate by the year, as past use costs dwindle and it incorporates original music and direct, exclusive creative partnerships. As a result, the total money Peloton is contributing to the music industry’s livelihood still isn’t that much, in the grand scheme of things.

But it seems like it’s only a matter of time before it dominates, right?

Here’s what I’ll say: It’s definitely going to be worth watching how Peloton’s music features further advance over the coming years.