In 2016, Jony Ive was contending with growing unrest within his design team at Apple. Ive had stepped down from day-to-day management duties, and Richard Howarth was elevated to vice president of design. This had created tension as Howarth had gone from ordinary member to leader of a close-knit group of about 20.

Ive had spent more than a decade working under Steve Jobs to become one of the most powerful people at Apple. His word was final. But Howarth didn’t have that standing. Ive’s absence created a vacuum, and other leaders at the company tried to fill it. For all Howarth’s gifts as a designer, he could become defensive and passionate when engineers challenged him. Such outbursts increased as operationally minded executives and engineers with seniority sought to increase their influence over designs.

The team he led had spent a year on a complete redesign of the iPad. Designer Danny Coster had led the effort. The Kiwi had been instrumental to the creation of the translucent iMac and had helped birth the name “Bondi Blue” after the beach in Australia. He had developed a refreshed iPad with more refined curves and a lighter body that felt natural in people’s hands. Some of the product designers working on it considered it so elegant that they said it would be the first model they would gladly purchase at retail prices.

However, Apple’s operations team determined that making the iPad would require building several new features from scratch. The first-time costs of new machinery, a new logic board, and other components would amount to billions of dollars, an investment that would take years to recoup. Those so-called nonrecurring engineering costs led Apple’s business division to suspend the iPad.

Such cost-conscious decisions frustrated some members of the product team. In the wake of it, Coster decided to leave Apple and join the action camera company GoPro as the head of design. It was the first high-profile exit of one of Apple’s core design team members. He had been at Apple since 1994. His would not be the design team’s last defection.

As work on Apple’s smart speaker, the HomePod, concluded, the lead designer on the project, Chris Stringer, decided that he was ready to move on from Apple. He had joined the company in 1995 and had reached the point where he was no longer as energized by the work as he had been over his last two decades of service. He approached Ive in February to advise him of his plans to leave. In addition to his fading interest, Stringer found the HomePod dissatisfying because Apple treated it as a hobby, depriving it of the cross-division focus it lavished on core products, such as the iPhone and iPad. Its development limped along, partly because Apple’s digital assistant, Siri, couldn’t order products, food, or an Uber as Amazon’s rival Echo could. In the back of his mind, he imagined the possibilities of a more sophisticated speaker. It was a project he knew Apple would never pursue. Speakers would never clear Tim Cook’s threshold and become a $10 billion business, so Stringer eventually set up his own audio company.

Amid the development of the 10th- anniversary iPhone, a similar restlessness pervaded the software design team. Imran Chaudhri, one of the top software designers, started plotting his own exit. The British American, who shaved his head and dressed in black T-shirts and jeans, had joined Apple as an intern in 1995 and solidified his role at the company as part of the team that had developed the iPhone’s multitouch technology. He had spent years working under Scott Forstall before being tapped by Ive to join a small group that developed the Apple Watch interface. He also presented at one of the company’s recent developer keynotes. Over time, he began to wrestle with how the company seemed to make fewer innovative leaps.

Feeling somewhat creatively unfulfilled, he decided the time had come to leave Apple. Following common practice at the company, he told Ive and Alan Dye that he planned to depart in a few months after he collected equity shares that he was due to earn as part of his compensation. Such an arrangement had become more common at Apple under Tim Cook. It was a contrast to Steve Jobs, who had punished deserters, refusing to rehire them and treating their departure like a scorned lover would.

A month before he was set to leave, Chaudhri wrote an email to colleagues announcing his planned departure. He told them that he would not be in the design studio but available by email until his last day. He reminded them of what they had done together at Apple to make products to empower people and told them that it was an honor to work alongside many of them. He was fond of a line from the Persian poet Rumi, who said, “When you do things from your soul, you feel a river moving in you, a joy.” Playing off that line, Chaudhri wrote, “Sadly, rivers dry out, and when they do, you look for a new one.”

The email alarmed Ive and Dye. They feared that the message Chaudhri sent could be interpreted to mean that Apple’s best days had passed. Its river had run dry. It was one thing for outsiders to say that the company was no longer innovative, but another thing altogether for that critique to come from someone who had helped birth multitouch technology for the iPhone. They worried it would poison morale and moved to contain the damage.

Shortly after the email, Dye fired Chaudhri.

The move had crushing financial ramifications. Chaudhri would no longer receive his shares. Stung, he complained to friends about the dismissal, telling them that Ive and Dye misunderstood his comment about the river. He explained to those people that the email was a personal reflection on his own lack of joy, not a comment on Apple.

Yet, inside a company wrestling with its own insecurities in the aftermath of its cofounder’s death, it was interpreted as a personal attack.

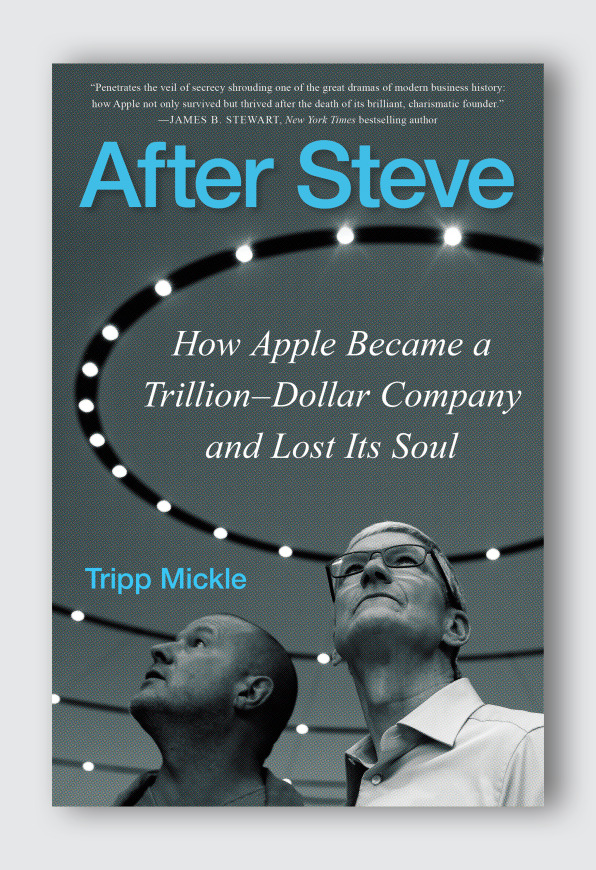

From After Steve by Tripp Mickle. Copyright © 2022 by Tripp Mickle. Reprinted by permission of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Tripp Mickle is a technology reporter for the New York Times, covering Apple. He previously reported on the company for The Wall Street Journal, where he also wrote about Google and other Silicon Valley giants.