Like all digital packrats, I’ve amassed a huge array of USB-C to USB-A cables over the years—but it wasn’t until recently that I realized how many of them were dangerous to my electronics and should be destroyed. Yours probably should, too.

Why destroy a perfectly good USB-C to USB-A cable? Well, it all goes back to the introduction of USB-C in 2014. The reversible connector was a big break from previous USB designs and was so complicated, many cable makers didn’t know how to build a safe USB-C cable. In a nutshell, each cable is supposed to have a 56k ohm resistor in it. This lets your phone, tablet, or laptop know if the USB-C port is connected to an older square USB-A port or not.

If the device senses the 56K resistor, it limits the amount of power it draws from the port. If, however, there is no 56K resistor, the phone or tablet assumes it’s connected to a higher-power USB-C port. In that state, the cable can potentially draw too much power from the port it’s plugged into, burn the port out, and sometimes cause damage to connected devices.

Got a pile of USB-C to USB-A cables? Some may be dangerous to your hardware.

Gordon Mah Ung

The good news? This problem was fixed years ago, and even the cheapest dollar store USB-C to USB-A cables I’ve bought recently were built to spec.

The bad news happens if you stumble upon a older cable that was built incorrectly. That may seem unlikely since this problem stopped being a problem four years ago or more, but no one ever throws away useful cables. We all dump them in a shoe box or coil them up and put them in a bag. Sure, I’ll eWaste old serial cables and printer cables as well as the odd MicroUSB and MiniUSB stragglers sometimes, but USB-C rules the world. Even I don’t need the cable, someone else might. Into the box it goes.

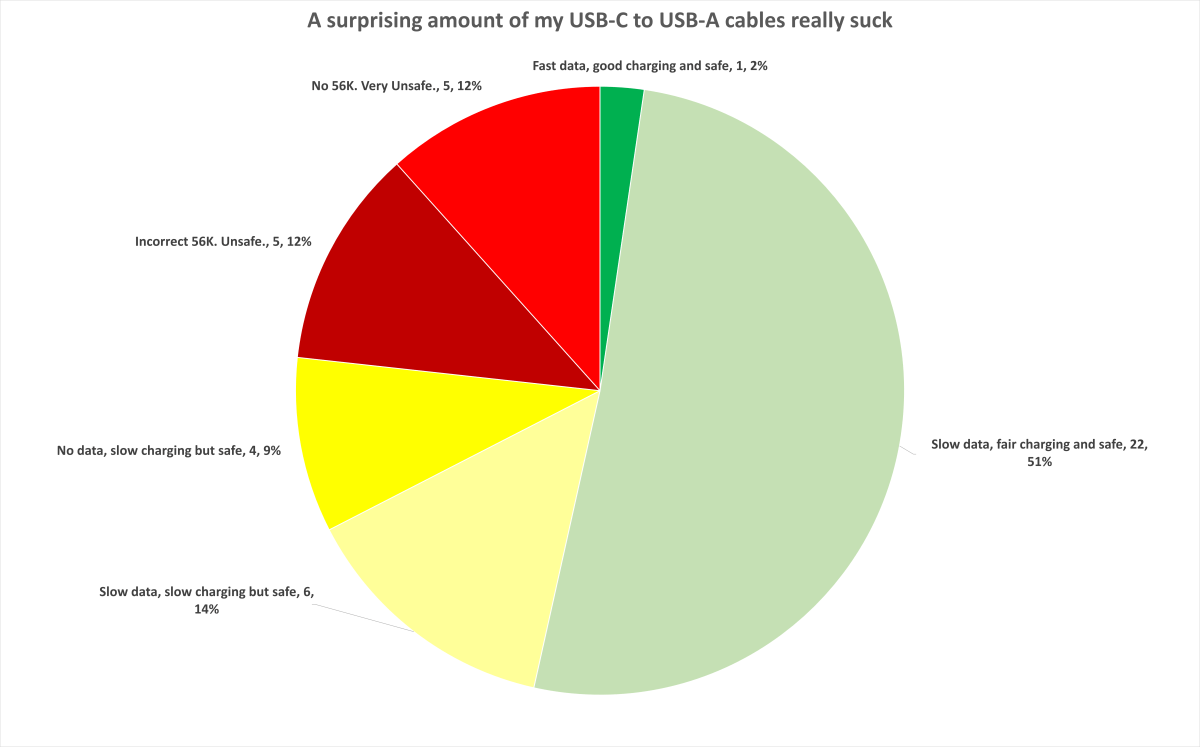

So in the interest of seeing how many actual bad cables are in my own collection, I grabbed just about every USB-C to USB-A cable I could to find out how good they are. Turns out I’m a digital pack rat and have amassed no fewer than 43 cables.

Only one cable was fast

You can see the result of my testing below but one of the surprises was just how many of my cables are absolutely terrible for transferring data. USB-C to USB-A cables can support up to USB 3.2 10Gbps if they have the extra wires. Without the extra wires, you typically get the basic 40Mbps transfer speed of USB 2.0. That means using a USB-C to USB-A cable for your NVMe SSD would make a large file transfer minutes instead of seconds.

Of the 43 cables I tested, only one cable supported USB 3.2 10Gbps speeds. Only one.

Besides grading the cables on data transfer rates, I also put them in bins based on the resistance each one had. For cables used mostly to charge devices, a cable with lower resistance generally means thicker or higher quality wires were used in construction, and more power gets to the device you’re charging.

The good news is most of them were decent, but I did find six cables that I tossed into the “bad for charging” bin because the resistance was so high. As a practical matter, it may not be much of a difference in the total time charged, but if a cable was going to be culled, I wanted a good reason for it.

Most of my USB-C to USB-A cables are lousy at data transfer and almost a quarter are down-right dangerous.

IDG

Charge-only cables

You know a cable connector standard has made it when companies start to truly butcher it by making cables that are literally charge-only cables. So it goes with USB-C to USB-A. Among my cables I discovered four charge-only cables that only had wires for charging. Why build cables this way? The main reason is to save money making them. But the problem with charge-only cables is they look identical to charge and data cables.

Perhaps worse, though, is these charge-only cables actually registered very high resistance. That ironically makes them terrible charging cables.

But on the plus side, all of the cables I’ve mentioned so far all were correctly wired with 56k ohm resistors. Even the most awful charge-only cable would prevent your phone or tablet from blowing up the USB-A port on your laptop.

That luck didn’t hold out. The remaining 10 cables were constructed improperly. Five were built incorrectly with either a 22k ohm resistor, or incorrect wires with the 56k ohm resistors. The remaining five had no 56k ohm resistors at all and should be classified as dangerous to use and probably slated for destruction. These were the cables that red flags were raised about in 2015, and are likely still floating around in similar boxes around the globe.

These compromised USB-C to USB-A cables could probably be used safely if plugged into dedicated wall chargers that can’t exceed the wattage your phone might ask for. The problem is two years from now, that dangerous cable might be used in a pinch and again get mixed in with good cables, potentially blowing up the port on a laptop.

And don’t make the mistake of thinking the dangerous cables only came from shoddy manufacturers. Having a name-brand cable won’t necessarily save you. Of the five dangerous cables without any 56k resistors, two came from a well-known phone maker, and another came from a very popular aftermarket cable maker that I still buy cables from today. Of the cables that were incorrectly wired, two came from another phone manufacturer. Another USB-C cable that didn’t make the cut that was supplied with a very expensive high-performance SSD. So clutching brand name to your chest may not always work.

This $65 cable tester is one of the easiest ways I’ve found to cull bad cables.

Gordon Mah Ung

How do you avoid a bad cable in your collection?

The easy way to fix this is to pick out the bad cables from your collection. Unfortunately there’s no easy way that I know of without spending money. The easiest way I’ve found is ADUSBCIM’s Cable Checker 2. It lets you easily gauge the capability of a USB-C-to-C and USB-C-to-A, as well as Micro and Mini USB cables. The small display gives you a quick and dirty view into the resistance of the cable as well as the presence of the 56K resistor. It can also tell you if it’s wired strangely (56K on two lines instead of one) or if it uses incorrect resistors.

At $65 on Ebay (I’ve not found it retail in the US otherwise), it’s probably the easiest way to test your cables, even though there are other, somewhat cheaper methods available.

The obvious problem? Spending $65 to test your collection of free USB-C cables makes zero sense financially. The cheaper option for most people is a thing no one wants to do: Destroy your current pile and just buy new USB-C cables which are known to be safe and good, for far less than $65.

Should you destroy your cables?

Whether you should take scissors to your older USB-C to USB-A cables depends on your comfort level with risk. If you’ve been using the same cable for years, then it’s likely fine. The bad USB-C cables mostly run the risk of damage when you connect a computer to the USB-C device, so if you only use them with chargers, the risk is greatly lowered. If a relative comes over, however, and unplugs that cable to transfer a few quick files from a phone to their laptop, you run the risk of it being damaged.

The last thing you may want to change is your behavior on abandoned cables. If Bob flips the bird at the company and storms out, leaving a couple of USB-C to USB-A in his cubicle on his last day—leave them alone. Rather than seeing it as a “free” pair of cables, you should probably just buy a new set of cables that you know are going to be safe.

My USB-C cables all suck

.

Gordon Mah Ung